Muttersprache

Tess Scholfield-Peters

[…] Maybe you can imagine, we are interested in everything you experience and there is nothing in this world we care more about. […] As we keep your letters, in the future, you, owner of a large estate, could delight your wife and children as you read out your very beginnings while sitting in a hall of your pompously furnished cottage (provided that your dear ones understand German, or you have learned so much English you are able to translate the letters.)

— Excerpt from translated letter from Max Pollnow in Berlin to his son Hermann in rural South Australia, 13 June 1939.

You won’t find more of a motley crew than in an after-work Beginners language course. I take my place, two rows from the front on the left, and watch as the others drip through the door, one by one. Liz appears and I wave and gesture to the seat next to mine. Liz does the additional homework and sends me funny phrases on Whatsapp after class. During the first class she told me she tried to learn Mandarin, her own mother language, but it proved too difficult so she took up German instead. She empathised when I told her I felt fraudulent holding German citizenship without knowing the language.

On my side of the room there’s Liz, then Matthew, an Uber driver who’s studying to be a personal trainer and learning German because his fiancée is from Hamburg. Next to Matthew is Jim, who’s pushing sixty-five and wears a loose-fitting singlet and rubber slides to every class. Jim bellows GOO-ten AH-bend with the strength of a baritone opera singer and the kind of twang you’d hear through a crowded restaurant overseas and instantly recognise.

People are still wandering in when Frau Ana enters briskly, her cropped mousy hair bouncing with each step. She greets us and we reply in our new language together, yet far from synchronised. Some Australian accents are so heavy on the words I wonder if people are taking the piss. We sit and face the front, staring at what Frau Ana is putting up on the projector.

Ist deine Schwester verheiratet? Das hier ist meine Tochter, sie lebt in Berlin.

I scan the textbook looking for any flickers of familiarity, of words I might have seen before or words that resemble English in some way. There are a few of those like Sohn, son, Bruder, brother, Mutter, mother. Would the unfamiliar words make more sense if my grandfather had kept his native tongue rather than disown it when he arrived in Australia? Whenever he raises a glass he says Prost instead of cheers and you can hear his German still, faintly, in the back of his throat.

But on my tongue German feels unnatural. And before my eyes the letters look strange in their alternate orders. I thought I’d be better at it, that it would come to me intuitively as if locked away on some cellular level, waiting to be spoken. But I’m struggling as much as everyone else, though not as much as Jim.

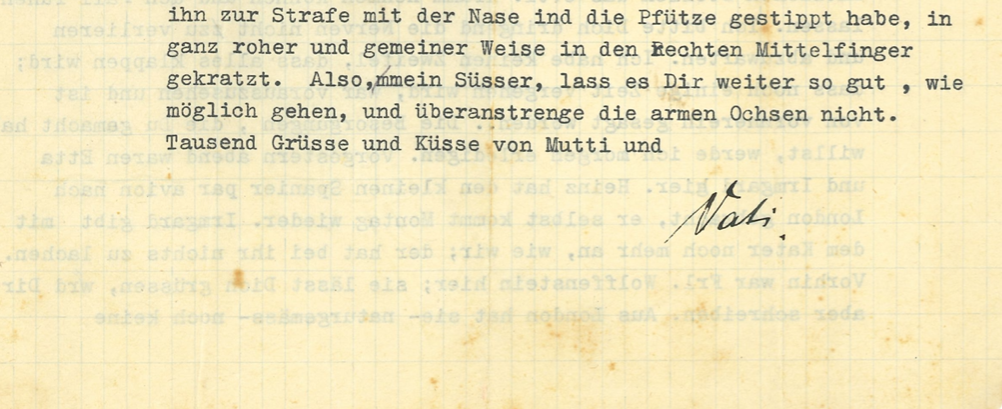

My grandfather kept the last letters his parents wrote to him from Berlin for years, all this time, and to my knowledge, he never showed them to anyone. Nor did he speak much about his parents at all. So to me my great-grandparents have always been incomplete characters. The irreconcilable gravity of their deaths during the Holocaust seemed always to overshadow who they were in life. I can’t read the original letters, only their translations which are mechanical, too literal. But even holding the originals I can feel something within them, in the type-written lines and my great-grandfather’s meticulous script, that’s deeper than ink and paper.

Frau Ana finishes typing out the words for every kind of family member and we progress to vocabulary that consists of items of furniture, words to describe furniture and inquiring about the cost of furniture.

Wie viel kostet der Tisch? Das sofa ist modern und praktisch!

After we’ve been assigned pages to complete in our Arbeitsbuch and the class has dispersed across Sydney, some to its farthest corners, I sit on the 412 bus along Parramatta Road. I think about what it would be like to read my great-grandparents’ letters without paying to get them translated. If I could read them myself, in the language they were intended to be read, would they sound any less distant? Maybe, but even then there are colloquialisms, people mentioned that I’ve never heard of, intimate lines of love and sadness written to my grandfather and only him. For me there is no message, except one small inference written on 13th June 1939: “As we keep your letters, in the future, you, owner of a large estate, could delight your wife and children as you read out your very beginnings.”

My great-grandfather, author of this letter, projected a future for his son across the ocean while he remained in Germany, trapped by his country until it turned him to dust. When I read his words I read that he wanted to be known, he wanted colour to be sketched into their grey silhouettes, he wanted his world pulled from the dust. But for my grandfather it must have been too hard to pass on more than the bare bones of who his parents were. So now I persist through fears of misinterpretation and imposture, deciphering foreign words, towards something that feels like familiarity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tess Scholfield-Peters is a Sydney-based writer and doctoral candidate at the University of Technology, Sydney. Tess is interested in third generation Holocaust authorship, representations of trauma and empathy in literature, and the intersection between historical and fictional writing.

As a fellow continuing German learner it always thrills me to read hybrid articles, and I can relate to your impressions of the German classroom as melting pot for entertaining, eclectic types. Best of luck with your learning and grandparents’ letters, and danke für dein schönes Schrieben.

Excellent Tess! Thank you.