Stuck in Honey: Disintegration by The Cure, live-streamed from the Sydney Opera House

Words || Mark Mordue

Tonight, The Cure performed at the Sydney Opera House. I did not get to go. Instead, like most of my friends—my Facebook world seemed suddenly entirely dead!—I tuned in to a livestream of the band performing.

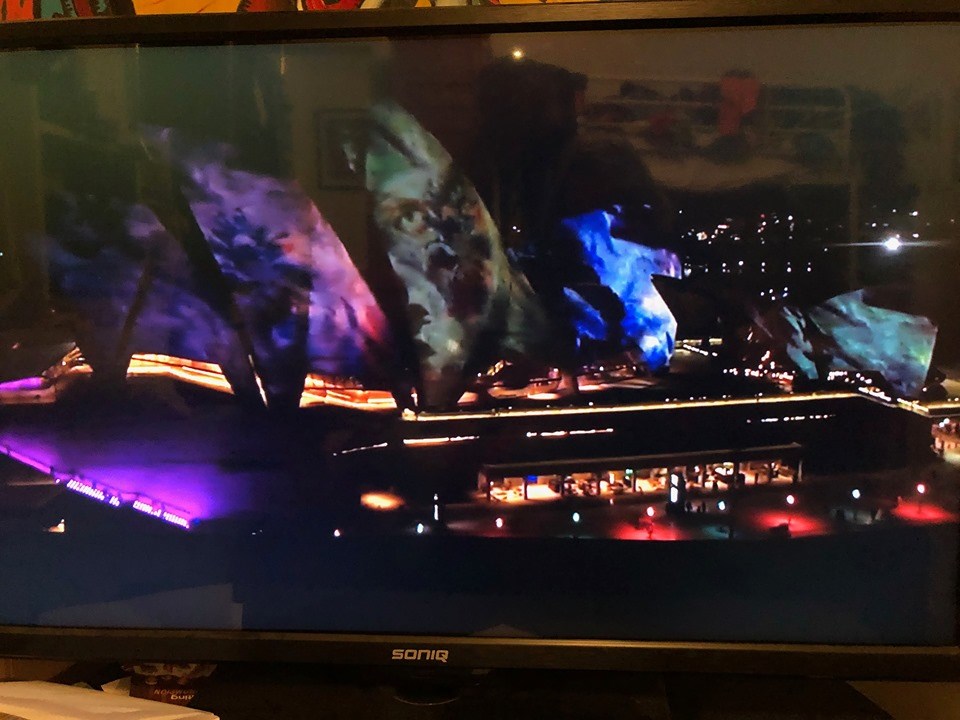

Everywhere later, I saw on FB that people were posting images of their television sets and computer screens, flaring images of Robert Smith and his group in various shades of blue and red and ray-gun white. All these little song fires that we had huddled around, apart and yet together tonight.

The Cure are, if anything, an unusual mix of emotional temperatures. Accordingly, they began with a set of rarities and mood pieces to warm up, or cool down, before their much-anticipated second set, a reincarnation of their 30-year-old classic album, Disintegration.

It was not till later I discovered these first songs were Disintegration’s B-sides and demos, sonic post-it notes left behind for more evolved creations. I admit this made me restless—and highlighted what can make The Cure such an acquired taste. Their first set swam between surfacing out of—and submerging into—their own deep sound.

Criticism of the previous three evenings at the Opera House suggested The Cure were somehow unsatisfactory, a mixed bag; that their show was based on a flawed or over-rated album. It seems more likely the tactical error had been the initial ordering of the two sets, performing the album first, then devolving into experiments and templates. Tonight, the band corrected this approach, reversing their set order, and rightly building themselves out of origin works like ‘Fear of Ghosts’ and ‘Babble’ before ascending (or is that descending?) into Disintegration itself.

Truth be told, I had already found the criticisms hard to accept. Mostly because I am a die-hard fan, caught in and defined by the skeletal teenage power of songs like ‘Killing an Arab’ (based on The Outsider, Albert Camus’s existential study of post-colonial horrors infecting a man’s consciousness in French Algeria) and those sudden, introverted riptides which moved me into their first classic album, Seventeen Seconds (1980).

I’d get to meet the band early on in their career, backstage in Newcastle after they had performed at an old art-deco theatre that was barely one third full. It was, I think, their first tour of Australia and most everyone in the audience was highly familiar with the raw nerve endings of Three Imaginary Boys. After playing the title track and songs like ‘Killing an Arab’, ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ and ‘Grinding Halt’ there was a literal sea-shift in everything, from the sound to the lighting, and we were treated to a preview run of Seventeen Seconds in virtually its entirety. It remains one of the best live shows I have ever seen.

Founded on what would later be called ‘gloomscapes’, Seventeen Seconds outlined in one-finger synthesizer washes and dream-tone guitar work all the emo anxieties that would go on to define The Cure for the rest of their career. I’d interviewed band-founder and then-keyboardist Lol Tolhurst for the local Newcastle uni student mag, a story I was able to on-sell to a national publication called Roadrunner. My first big break as a rock journalist! Tolhurst had been more than friendly on the phone and finished by saying ‘come on backstage when we’re there’. I took him at his word.

A friend and I made our way through simply by saying the band said it was ok. Security was not what you would call tight. In a small, hard-lit room with all the personality of a cupboard The Cure sat entirely dressed in black, drenched in sweat, heavy with make-up that was now running, totally exhausted by their show. It was not that anyone was unfriendly. Just hopelessly awkward. A group of boys who didn’t know how to speak.

The band were all 19-years-old. And I was 18.

If The Cure are the preeminent goth band that begat emo, it’s a truly cathedral atmosphere they occupy: ringing, heavy, and transcendent by turns, a music of aching and romance that implies movement across great spaces, be it spiritual, emotional or physical.

The fact Smith could so easily turn his hand during the 1980s to pop hits like ‘The Love Cats’ (reputedly inspired by a reading of Patrick White’s The Vivisector and a male character whose lover’s husband drowns some stray cats in a bag) and ‘Close to Me’ (based on the bad dreams Smith had as a child and accompanying, even life-long feelings of claustrophobia) was almost shocking to fans when it first happened.

Yet those songs were not so far from the melodic, driven hooks that first defined the band’s lean post-punk phase on Three Imaginary Boys. Smith had gone on to drown himself in introversion across albums like Faith (1981) and Pornography (1982), but a bass-driven hit like ‘Primary’ surged out of the doom infectiously. Conversely, the narratives behind Smith’s brightest and jauntiest pop tunes suggested his dark materials were merely hidden away. It would not be so long before they bloomed into the open again.

I have often felt an Australian group like The Church share kinship with The Cure, a band just as capable of making music that people love, a band just as easily marked by some restless need to repel us or push us into heavier territory.

To me, this is the world of the poets. Where Robert Smith and Steve Kilbey join lyric magicians like Marc Bolan, David Bowie, Iggy Pop and others in the underworld of our own imaginations. For some reason, I think of a short story told to me second-hand by a friend: the tale of a man who discovered he was being eaten alive from the inside by flowers. These poets, these men, are that one man of terrible, beautiful flowers.

Having seen The Cure now three times across their career, I can vouch for a powerful physicality to their sound that can’t be felt watching a so-called live-stream. The band have a grand rep as synth mood-masters and guitar drone kings for very good reason. Live they deliver dense masses of sound.

The same music that I sometimes felt was delivered on record to alienate listeners, grips you live with all the awful thrill of an immense river. In short, music I would reach to switch off at home overwhelmed me in concert, a kind of future metal roosting in a sonic purple haze the likes of which I had not begun to know before seeing them.

At one point tonight, giant splashes of rain echoed out across the backscreen projections. Among the metaphors one reaches for to grasp The Cure – bells, mist, night, flowers – water is capital among them.

Perhaps, this is the reason why the ‘livestream’ from the Sydney Opera House got better and stronger. And with it the currents of meaning in certain songs. I have listened to ‘Lullaby’ a thousand times but it was only a few weeks ago it dawned on me the song transports a paedophilic assault into the realm of dark fairy-tale. ‘Lovesong’ is a siren call to a lover being abandoned, and an unresolved message of longing to return. “Homesick’ is so grand it hurts, a song that is what it says it is, all the while it begs for the listener to help them run away from home forever.

All of this feels like a voyage: there is something about The Cure’s alchemy that is taking us across a world of painful-real and fantasy-dream so that we might end up in the harbour town of Hope. I guess that’s why I like them so much. It’s also why their choice to end the show with a cover of Wendy Waldman’s ‘Pirate Ships’ was both surprising and somehow right: “See the people in the stars, child. They will sail right through your window.”

Simon Gallup roams the stage tonight in white jeans, Adonis long hair, shining yellow bass, the longest surviving member of The Cure apart from Smith, and almost the band’s star performer. Watching he and Smith on stage it’s clear how close they are. Reeves Gabrels, formerly of Bowie’s Tin Machine, quietly handles guitar and sonics to Smith’s right. Roger O’Donnell, ex Psychedelic Furs, on keyboards, stands head bowed or head back, as if praying to someone above or something inside him (or both). Drummer Jason Cooper, seems to be all through the songs. His credit for having done the soundtrack for the horror film called From Within seems entirely right. Somehow, these great musicians merge into one animal, each rising and falling in distinction. Reeves Gabrels has observed in an online interview that one of the biggest things he has learnt with The Cure is how to work in an ensemble, a development he was unaware of needing to make until he joined the band.

Out front, of course, is Robert Smith, a guitarist as unique and influential in his sound as a Neil Young or Tom Verlaine ever were. A guitarist whose talent still surprises, as if we hardly knew it was him there playing these songs all along. Gabrels, no slouch himself, is certainly a fan, having noted Smith’s harmonic approach and European playing style, with its hints of Arabic and gypsy shapes, and other roots the came from listening obsessively to David Bowie’s Low. It’s true, Smith is one hell of a creative musician.

There is nonetheless an element of Smith being caught in the headlights as he performs. He seems, to me, to be a person of great pain and loveliness at once. The sighs. The faint hints of self-mockery between one or two songs, which also suggest, of course, a flash of viciousness. The desperate, imploring, loving lyrics – “just one more… inspire in me the desire in me to never go home”. The blue eyeshadow that makes his eyes seem too bright in the stage light. His blighted physicality, overweight and garish, as near to becoming a beaten-down clown or a crazy old lady as any Goth Romantic hero of times’ past – a decayed and off-kilter image that reminds you of Charlie Chaplin in cobwebs, and something tragic that also makes me think of Oscar Wilde wandering through Paris alone. Who knows why such thoughts come? But come they do.

Yes, Robert Smith is growing old and it’s not easy to live with what that ageing does to you. And yet the young man is still there too. He treats us to an encore version of ‘Three Imaginary Boys’, an unintentional anthem to the origins of his band. It makes Smith smile, a song of being that has now become a song of remembering. I can’t sum any of this up easy tonight. I guess I just want to tell you in all this that Robert Smith is beautiful in his own strange way. And that his band are a wonderful band. And we are fortunate to have shared a cold, dark autumn night with them, remote as their fire may have been on a screen.

And so, you see… I was not there at all, but I was there.

Disintegration by The Cure was livestreamed from the Sydney Opera House on Thursday 30 May 2019. It’s available to watch on Youtube for free.

About the author

Mark Mordue is a journalist, editor and poet based in Sydney. His poetry collection Darlinghurst Funeral Rites mapped the inner city post-punk music and art scenes of the 1980s. He is currently at work on a long-awaited biography of Nick Cave; another collection of his own poetry; and the second draft of a novel set somewhere in the very near future.

great review – something quintessentially english about the cure, the cobweb-covered dreamscape of miss havisham or one of shakespeare’s magnificent fools… we weren’t there but there was a charged sense of mcluhan’s global village that night