Old Narratives, New Narrators

By Nasrin Mahoutchi-Hosaini

Karl-Heinz Stierle writes, “The prototype of the narrator, is the storyteller. We have a quite definite conception of him: he is old rather than young; in fairytales he is the kind uncle or—if it is a woman—the kind aunt or grandmother. He does not stand up, but is seated—in an armchair, on a sofa, or by the fireplace. His hour is evening, after work. He likes to interrupt his story in order to have a puff on his pipe or cigar (rarely a cigarette!). His movements are slow; he takes his time, looking at his audience one after the other, or he gazes thoughtfully up at the ceiling. His gestures are sparing, his expression reflective rather than animated. He is quite relaxed.”[1]

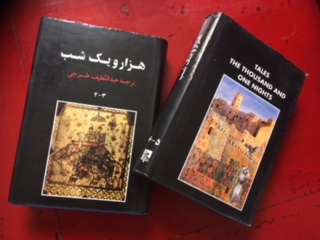

The first narrator/ storyteller I knew as a child was Shahrzad; the young and beautiful daughter of a vazir.She is seated at the king’s bedside. Her hours are from late at night till early morning, the time when the king leaves his palace. She weaves stories one after another to keep the king engaged, interested, seduced to delay her death and the death of any other virgin girl in the country.

Almost all the stories in the One Thousand and One Night end with this phrase: as down started and sun rose, Shahrzad stopped her story and left the rest of the story for the next night. (My translation).

During the Iran and Iraq war there was curfews. When the sound of sirens warned the citizens of bombing, we took refuge in our basement. Usually, during the danger people helped one another and that was what my parents used to do. We had a neighbour who was a primary school teacher, a young and beautiful woman who lived alone in her apartment next door to us. Her long black wavy hair always was dancing around her round face. A pair of arched eyebrows gave her the look of a Persian miniature beauty. Here, I will call her “Afsaneh,” a Persian word for saga, or fable. This is also a female Persian name which with a suffix “Goo,” it becomes Afsanehgoo, it means storyteller.

Her stories were an oral anthology of old and new; thousands of anthropomorphic beings, gods, devils, beasts and mermaids met with daily merchants, innocent, gullible people and selfish and hypocritical merchants and clergy, on every corner of fantasy cities and bazaars. Each of the stories contained at least one female character. She was a gorgeous storyteller who stirred into her stories moments of poignancy and despairing tenderness, as when her dark heroine met the eyes of a hero. Afsaneh’s heroes and heroines were also often men and women in todays’ life living in the ordinary cities and streets. Sometimes she even used the name of our own street. In those moments we got excited, wanting to know whose stories she was telling. Afsaneh delayed the nightmare of the war, changed our teeth chattering fear into the wide open eyes’ of listeners. She sometimes moved around in a circle, using her long arms and body to relate her Nagal, an oral storyteller in the Persian tradition, as if she was a Dervish, dancing in a circle, facing her audience in the dark. With the requirement of the rhythms of her story, she raised her voice up and down for effect, drawing us away from the horror outside our basement.

Sometimes in the middle of an adventure, her voice would drift into a kind of monologue, telling little significant family stories, the kind that we would hear in the living room from our elderly aunts or uncles or our grandparents. In those moments, our story teller would lose her ability to ride our fear away from reality. On the contrary, she would stop, tilt her head toward the sky, contemplating the horror of the unseen bombs raining upon our city. In the dark and her silence we listened to the bombing.

Our storyteller was young and inexperienced with the horrors of real life. Nevertheless, she would continue and stretch the length of her story to the early morning, till we heard the sound of birds singing in the backyard, when we were let out to pursue our daily life. She would say: well, here, I stop my story and will continue again at the night.

Perhaps our perception that the story teller should be old comes from stories themselves. Fables, sagas, old legends and tales of evil come from far away times and places, real or imaginary. Now in the twenty first century we are re-experiencing evil; bombing, shelling and devastating horror. It seems that it doesn’t matter if the story teller is from the twenty century – as my Afsaneh was, or from the ninth century – as Shahrzad was, the oral story still belongs to old and ancient civilisations and traditions; to the time when tribe people gathered around the camp fire to listen to the stories of heroes and heroines, stories of ordinary people who live extraordinary lives facing demons of the every day. They told stories to keep the fear away and encourage new life.

[1] 1: Karl-Heinz Stierle refers to Weinrich in his essay: K. H. Stierle, Story as Exemplum – Exemplum as Story; The New Short Story Theories, ed. C. E. May, 1994. Ohio University Press; Athens. P 18.