Tracing body-and-bloodlines

by Roanna Gonsalves

A book, like a person, holds a tangle of ancestors within it. Sometimes, tracing the literary influences and resonances in a book, its bloodlines, is as straightforward as tracking back through the parish register of births and marriages. Often, the process is slightly more complicated, involving a piecing together of half-remembered conversations, silhouettes of words, a sifting through the obfuscations of the imperial project imbricated with patriarchy, in order to get to the greatest grandparents.

Since its publication about three months ago, my book The Permanent Resident has elicited questions from some readers about its sex scenes, the masturbation scene, bodily fluids on the page. My work, like the work of many other South Asian women writing about the female body, has bloodlines that go back over two millennia. This article pays homage to the early ancestors in a long line of women writers whose work has been lost, destroyed, found, has survived, has been translated, and now thrums through our bodies in the 21st century.

The earliest known anthology of women’s literature, possibly in the world, is the Therigatha, a cluster of songs in Pali composed by Buddhist nuns in India, contemporaries of the Buddha, around the 6th century B.C. Here is the poet Mutta rejoicing in being unshackled from the strictures of a brahmin household, savouring her newfound liberty through Buddhism:

While the Therigatha is primarily about the body, mind, heart of women transformed through the Buddha’s teachings, the earliest anthology of secular Indian verse is the Gathasaptasati.[2] It was compiled by a king around the second century C.E. but is said to draw on an oral tradition going back centuries earlier.

The verses in this anthology seem so astonishingly contemporary, as if written just this morning about 21st century female desire. The translator of these verses, the eminent poet and critic Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, notes how “with great precision they map out the territory of love, from the coastline of the sidelong look to the fertile valleys of infidelity.”

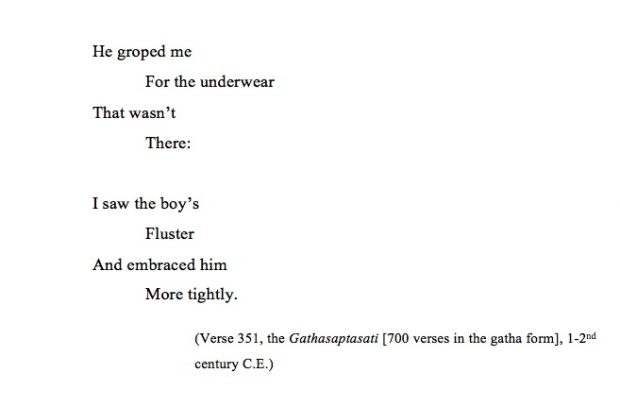

Mehrotra tells us that about half of the verses in this anthology have been assigned to individual poets, only a few of whom are women. Yet the speakers of the poems are almost all women, of varying ages and sexual experience. Here is one where an older woman takes a young lover:

Here’s another sharp flash of female self-assuredness, speaking across two millennia:

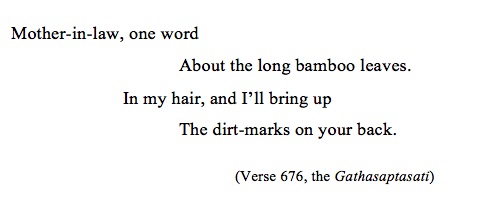

Consider this threat from one woman to another:

With the briefest of exertions, it topples the stereotype of the sexually passive, faithful wife in pre-colonial India, as it demolishes the platitudinous image of the asexual older woman / mother-in-law, replacing both with sharp, subversive streaks of concupiscence. All this is from a literary tradition that is over two millennia old.

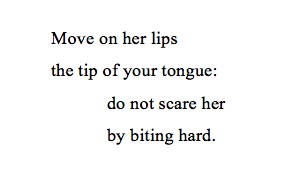

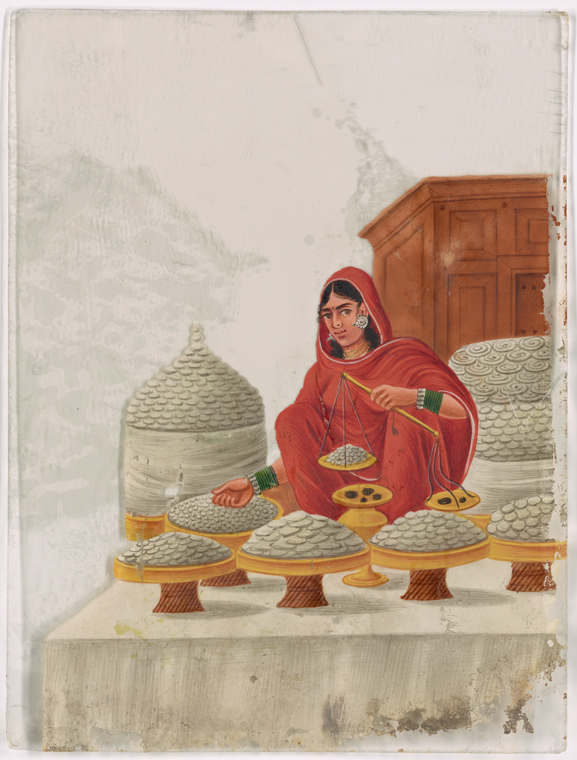

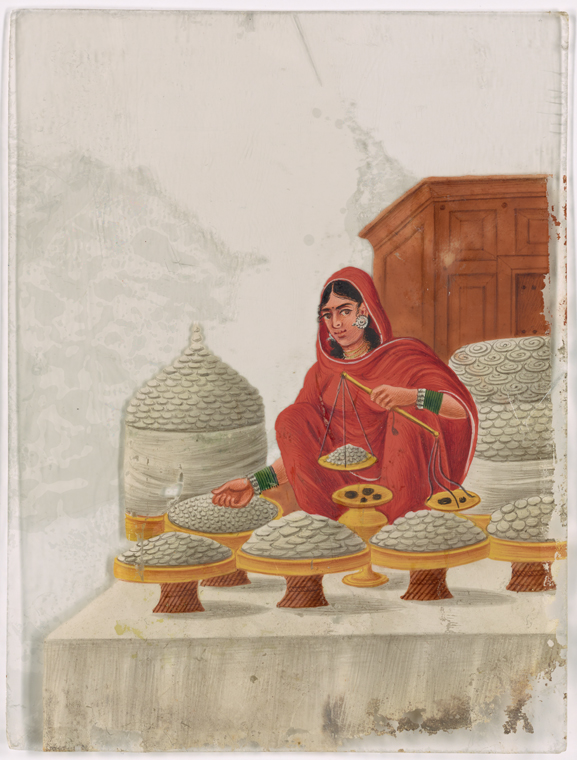

In the 18th century, there is, among other fine women writers, the courtesan Muddupalani, working in the court of Pratapsimha, a Nayaka king of Tanjavur. She is the Telugu author of the erotic epic Radhika Santwanam (Appeasing Radhika) [3], a revisitation of the story of Radha and Krishna, about the woman taking the sexual initiative in a relationship. Here is the speaker advising Krishna on how to make love to his new bride:

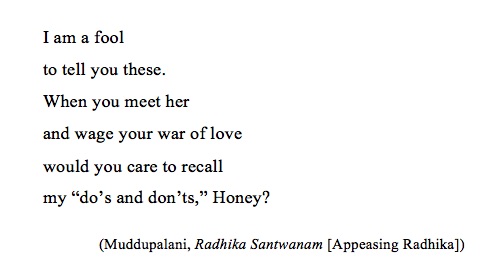

The poem proceeds with more detailed instructions on foreplay, and then turns imploringly in the last lines:

In her time, Muddupalani was considered a great poet and scholar of Sanskrit and of Telugu literature, even by her harshest critics, as Susie Tharu and K. Lalitha tell us. In the early twentieth century, another feminist courtesan and patron of the arts, Bangalore Nagaratnamma printed a new edition of Muddupalani’s erotic poem, because she thought the existing edition didn’t do justice to the brilliance of the work. However, the publication of this new edition caused a furor. A prominent male social reformer branded Muddupalani an adulteress, and the British government felt that this obscene book would endanger the moral health of their Indian subjects. Despite strong protest by the literary community, the British government banned the work [4]. A new edition of this work was brought out only after Independence in 1952.

These are the body-and-bloodlines that course through the work of many South Asian women’s writing about desire, lust, and love. They may not be the only ones, in a tangle of ancestors. But they are ones that deserve further celebration.

[1] Translated from the Pali by Uma Chakravarti and Kumkum Roy, in Women Writing in India, Vol. 1, edited by Susie Tharu and K. Lalitha, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1991.

[2] Translated from the Prakrit by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra as The Absent Traveller: Prakrit Love Poetry from the Gathasaptasati of Satvahana Hala, Penguin Books India and Ravi Dayal Publisher 2008 [1991]. Published in Australia in Collected Poems: Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Giramondo Publishing Company, Artarmon, 2016.

[3] Translated from the Telugu by B.V.L. Narayanarow, in Women Writing in India, Vol. 1, edited by Susie Tharu and K. Lalitha, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1991.

[4] See the Introduction to Women Writing in India, Vol. 1, edited by Susie Tharu and K. Lalitha, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1991.

Roanna Gonsalves is the author of The Permanent Resident a collection of short fiction published by UWAP in November 2016. Her series of radio documentaries entitled On the tip of a billion tongues, was commissioned and first broadcast by Earshot, ABC RN in November and December 2015. It is an acerbic socio-political portrayal of contemporary India through its multilingual writers. She received the Prime Minister’s Endeavour Award 2013, and is co-founder co-editor of Southern Crossings. She has a PhD from the University of New South Wales. For more information see roannagonsalves.com.au