Jep Jep

Oliver Mol

1

Her name was Jessie, or Jep, or Jep Jep, or Jeplestein, though certainly not Tinsel, her name before we picked her up shortly after moving to Texas, before Y2K, when people stockpiled water, canned goods and guns at Walmart, preparing for the end. Jep Jep, as we mostly called her, was a mother, a huskie X Australian Shepard, or an American Eskimo X Wolf who had been abused and abandoned and forgotten to the RSPCA. One afternoon, my mum and sister were walking through the mall when they saw her in a shop window. My father, then, was vehemently against getting a dog, but the way she cowered in the corner, pleading, almost begging, not the way most dogs do: energetically, with their paws, their necks, their heads, but with her legs crossed, elegantly, with her eyes, downcast⎯it was too much. So they did a lap of the mall, discussed the matter and before they passed, again, that horrific Abercrombie & Fitch store, returned, reasoning that they couldn’t just leave her, that Dad would understand, or would grow to understand, or would, perhaps, even grow to love her too. But when they arrived, she was gone. My sister was eight, heartbroken. She burst into tears, and they left assuming the worst: that someone else had picked her up, that she was gone, that she was never coming back. I just hope she didn’t get picked up by some asshole, my sister said, a word she’d learned from my father, who, famously, loved to call strangers assholes, and my mother didn’t even correct her because she hoped it was true too.

2

The following week, however, my father and sister returned; Dad was trying to find a tie with a sailing ship on it, but then my sister sprinted into the store. DAD, she screamed. DADDD! TINSEL’S BACK! Who the hell’s Tinsel? Dad asked, or I like to think he asked, now, because it’s funny, and because he was always asking who the hell certain people were⎯like the time, years later, we were in the car listening to the radio announce that Flume had won a Grammy and Dad turned around and said, And who the hell’s PHLEGM?⎯but in the end my sister said they couldn’t leave her, not again, and so they called Mum and made a deal: we can bring her home, Dad said, but she’s not my responsibility. I don’t have time to feed or train her, that’s up to the rest of you. And so Tinsel came home in the back of our minivan, cowering in the corner of her straw-filled crate, occasionally whimpering, though mostly keeping quiet⎯the way she knew was safe; the way she’d been taught her entire life.

3

What the hell kind of name is Tinsel anyway? Dad said. What is she, an ornament? Something cheap and flashy? No thank you. And so, in principal, Tinsel became Jessie, though, in reality, she struggled to forget her old name, her old life. Around men: my father, the postman, our neighbours, she would almost squat, her tail between her legs, as if she had been struck, or almost struck, or was replaying the memory of being struck long ago. Course I was ten or eleven, then, and my brother was, perhaps, seven, and mostly she would bound up to us: her whole body shaking, wagging, playing⎯but there were other times when she would pause, as if remembering what we were capable of, of what we could become.

4

The details are shaky, though with a little research we learned she’d been abused. Her owner beat her for years, and after she sired six puppies, he abandoned her on the street. During those first weeks, months, she didn’t bark, and we wondered, for a time, if she even knew how. It’s okay, we’d say, or my father would say, bringing her fresh water and food while she retreated, gazing up at him from the grass, this mother who looked like a wolf or a racoon⎯and then, when he was far enough away, she would nudge forward, pausing, before nudging forward again, unsure of the water and food and this new emotion, this strange man who seemed to suggest that the world could be kind.

5

Right, Dad said. She gets three walks a day. So get your barge-arses moving⎯she’s a sled dog! Get on your bikes and take her for a ride. And so we rode, around and around that awful suburb called Hayden’s Run, around suburbia, with all those American flags, huge and crass like the people, spilling onto the lawns of houses, and Jep Jep would run beside us, usually ahead of us, though occasionally behind us, only to stop, suddenly, as if she had forgotten, or remembered, who she was. What I remember most is not our bloody knees or shins or elbows, but the way her eyes would roll to the back of her head, how her back would twist and her head would tremor and how her tail would spasm⎯and then how she would pause. I like to think of these moments, now, because they appear frozen in time, a comma before the crisis, when we were young and Jep Jep was alive, before we would inevitably fall and Jep Jep would go what we called “Full Psycho”, sprinting into the bushes, into brush, running, running, from herself, her past, anywhere, away⎯but perhaps that is all a fiction; perhaps she was running towards something too, and these glitches were not glitches but celebrations, uncontrollable expressions from deep inside that she was finally free.

x

x

6

x

Did you ever have dogs growing up? I asked Dad, one afternoon, but he said, No, that he had never had dogs, that his parents hadn’t been interested in dogs, that, instead, in Canada, they had had cats, one or two of which, during the winter and seeking warmth, had crawled into the family’s car engine and died. Mum, on the other hand, had had several dogs. The first was called Porcia, named after the wife of an obscure politician from the late Roman Republic who took a leading role in the assassination of Julius Caesar. The second dog was called Gurly, an old, beautiful dog who was run over on Christmas Eve. The third dog was called Lucy who may or may not have drowned. The fourth dog was called Manfred, a miniature Collie who had hip surgery and lived a long and prosperous life. The fifth was called Toby, a Labrador cross that Mum brought home from the market, who chewed all her father’s socks and ripped sheets off the line and who, after Mum left home, was donated to a posh neighbour and lived like a prince. Then there was Jojo, Mum’s sixth dog and our family’s first, who spent all her time digging holes and escaping, running the streets of Canberra, hanging out at Erindale shops⎯when we left we gave her to a friend, and not much changed because it was almost like she’d never been ours at all. The next, the last, was Jessie, Jess, Jep Jep, Jep.

7

In that first year she barely came into the kitchen, preferring to stay in her crate, in the laundry. Jep Jep! we would say. Come on! Come on, girl! But she would not come; the laundry was hers; she knew that space, though I wonder, now, if it was more than that, something as grand and simple as not recognising her new name.

8

But if I could only tell you about her hearing, how she heard Dad coming home long before anybody else, before his car reached out street, how her head would raise and her tail would wag and how she would sprint from one side of the yard to the other, not caring, for a moment, about the squirrels or other dogs roaming their yards, and how she whimpered and how she barked⎯how, eventually, she remembered how to bark. If I could only tell you about her paws, how she placed them, one over the other, like a lady, as my mother would say, at first, breaching the threshold between the laundry and the kitchen, and then, slowly, one evening, moving, cautiously, into the kitchen, her paws silent as she came to a rest, not with us but close to us, away from the table. I was, maybe, twelve, then, and after dinner I would practice jumping exercises in our garage from a program called Air Alert 2. It was hot during those Texan nights and I would spend them, determinately, alone, jumping, trying to increase my vertical, to change, to make basketball A team, to be stronger, better, to fit in, whatever that meant. Sometimes, Jep Jep would sit with me, panting on the concrete, though usually I would find her afterwards, sitting, facing Mum and Dad in the living room⎯her paws now millimetres from the kitchen hardwood, living room carpet divide. I remember sometimes we would pick her up and hold her on her back as if she was a newborn, taking her from the kitchen to the living room, and sometimes, if we made it that far, even upstairs. But mostly she would whimper and squirm, sometimes even escaping and sprinting back to the laundry, wetting herself, as if remembering some terrible thing that none of us could know.

9

x

It’s almost as if this were a eulogy, I think, now, and perhaps it is.

x

10

x

One summer we took her to Gardener Falls, this national park several hours outside of Houston with campgrounds and a river and those trees you could jump out of into that murky brown water. Jep Jep wasn’t an ocean girl; the waves scared her. But that summer, she followed us down to the river. My sister jumped out of the highest tree first; my brother and I followed, and then, splashing and laughing, we called Jep Jep to join. At first, she sniffed the water. She paced. But then, from the bank, she jumped. The river was wide, maybe 60 metres across, and she swam to us, around us; we were standing in the shallows, then, and she rounded us up as if we were her sheep, head above the water, her nose sniffing little sniffs, before returning to the bank. Then, perhaps a minute later, she jumped into the river again, this time swimming father, past where we had been, perhaps a quarter of the way across before looping to the shore once more. On her third trip, she swam all the way to the middle, and we cheered; this dog who had now taken the form of a tugboat, or a beautiful drowned rat, u-turning in that river, panting and paddling through the water that reflected like quartz the in that afternoon sun. For a while, she relaxed, breathing, staring out across the river. By now, we were packing up; the sun was fading, but then, as Dad put away the last of the chairs, she leapt into the river for a final time, and we watched her swim clear to the other side. On her way back, we cheered, hollered. We yelled, Go Jepppp! Wooohooooo! Come home! And I swear to God when she returned she looked different, like a mother who had never lost her children⎯or a mother who had⎯daring to trust again, to believe that she might be okay, that she might not be alone.

11

Well, we can’t leave her here, Dad said, as we folded our sausages into bread, Jep Jep munching her own sausages that we fed her, in secret, during dinner on the kitchen floor. Dad had been made redundant; we were to go to Hong Kong, or return home, and the idea that we might leave had seemed impossible until then, though, in truth, it was something I’d prayed for. I was fourteen and I didn’t understand America and I didn’t understand myself. Sometimes, in the evenings, I would lie on the laundry floor, my head on Jep Jep’s back thinking about all the things that were wrong with me even though I didn’t know why. Why are people mean? Why are they cruel? Where are my real friends? When will I get hair under my arms? When will my dick grow? I just want to grow. I’m alone. But Jep Jep would just lie there, breathing, taking my weight⎯this mother who knew, instinctively, that the trick was just to keep breathing.

12

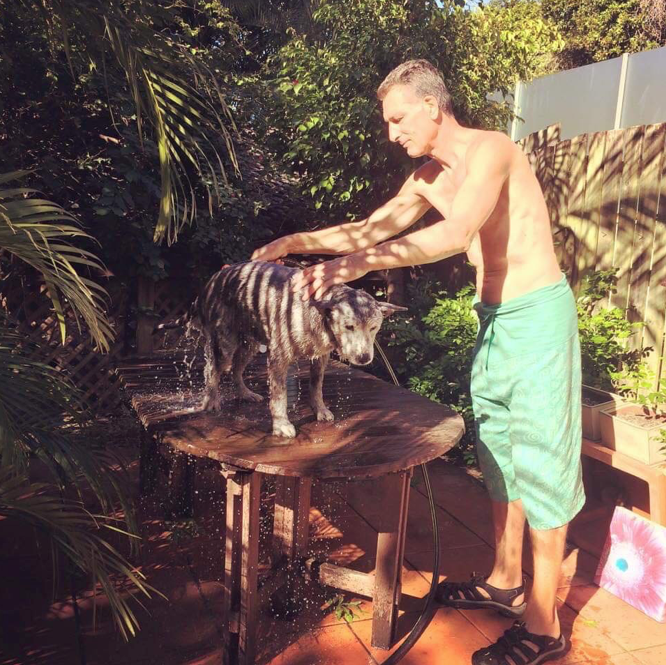

So we returned to Brisbane, to that house my mother ran as a Bed & Breakfast on Kelvin Grove road, where Jep Jep lived mainly in the backyard under the stairs, and in the summer we would get her shaved, and she would return changed, as if a child, a puppy, frisky, and with a pink bow in her hair. Sometimes, when I picture her now, all I see is her naughty face and that pink bow: lopsided and filthy from chasing those fucking arsehole possums around the yard. What’s that, Jess? Dad would say as the possums hissed their devil hisses and her ears pricked up and she prepared, as she had always done, to go “Full Psycho”. Fucking arsehole possums! Get them, Jess! Dad would say, and then Jess would be off, sprinting, clearing, or almost clearing, the 11 stairs from the deck to the backyard, and the possums would flea, and Dad would tell another story about how heroic she was, saving Mum’s flowers, those basil plants and parsley plants and pansies and dwarf snapdragons and bamboo and all the other plants and trees that lined our backyard, that familiar space within the Bed & Breakfast that, even though was communal, Mum had made very much our own.

13

I remember, a year or two after high school, I travelled overseas, and my friend Nadia would walk Jessie around Kelvin Grove, Red Hill, Paddington, listening to The Shins or Elliot Smith or Rufus Wainwright’s Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk, and that when I returned she said that I’d gotten bigger, that I’d filled out, and that when she walked Jessie around the block lots of guys would stare, but she wouldn’t notice, or barely notice, too busy lusting over the idea of having her own dog that she could walk after school; And I remember the New Years my parents were away and Toby, Ben and Jack flew from Sydney to Brisbane and we went to a party and got high and separated and in the morning Toby and Jack, drinking whisky and eating Tramadol, shoplifted dog shampoo, conditioner and treats from Coles and when I returned to our house, my parents sanctuary, three chairs were broken and Toby had put our trampoline in the pool and was sitting on it, grinning, because he’d washed Jep Jep eight times and she no longer smelled and he yelled, I even fed her too!; And I remember the night it hailed and the hail banked up and Brisbane turned white and we took Jep Jep and some old skate decks to the golf course and Jep Jep rolled around in the slush that we pretended was snow and we used the skate decks as snowboards and put Jep Jep on the skate deck and watched her ride down the hills.

14

It’s hard to know how old Jep Jep really was. At some point, we stopped counting⎯but one evening she fell down the stairs. By now, my sister and I had finished school, though perhaps my brother had too; we were eating on the deck when we heard a thud, then a thud, then a thud and then nothing. Dad was the first to get up, and we sat there, at first, confused, and then, in a sort of paralysis, staring at one another as we heard Dad say, It’s okay, Jess. Come here, girl. Everything will be okay. Her back legs had been going for a while⎯occasionally, accidentally, she sat mid-stride, other times she dragged her paws along the ground, sometimes she simply urinated where she sat as if she were an old lady, a grandma or a great grandma riddled with arthritis just trying to make it to the bathroom, which, in fact, she was. Dad kept saying, There, there, as he picked her up and carried her to the garden to pee. That’s a good girl. And I still remember them emerging from the stairs: Dad holding her like a newborn, then placing her down, fetching her water, a piece of chicken, a treat, running a brush, gently, through her coat, her hair that had begun to patch and bald, this wolf of a dog who had begun to resemble, now, an elderly racoon, who, even in the weeks after, even when she couldn’t, would still attempt to scale the stairs when we, though especially my father, got home.

x

15

X

And so my father went about rigging up some wheels. He went into the shed and sketched some prototypes and conceived a harness and drove to Bunnings to find the wood and bearings and all the materials required to make Jep Jep mobile again. But that weekend, as Dad was putting the final touches on what we called “The Rig”, my sister asked if she could take Jep Jep to the country. Someone was having a party. There would be new smells, people, a bonfire. Just make sure you take care of her, Dad said, with the same tone he always used when expressing, or trying to express, his feelings, or the things he couldn’t live without. And so, that weekend, she drove, Jep Jep on the back seat, listening to old tapes: Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the city becoming suburbia, then grass and trees, then plains and more plains. After they arrived, Brigitte helped her out of the car, and she sniffed the earth, the plants⎯a bonfire grew and Brigitte carried her towards that too. People drank Bundaberg Rum and XXXX and spoke about their lives or made jokes or pretended to be different or remembered their lives from long ago. Jep Jep licked the ground and stared at the fire; people patted her patchy coat and she smelled their smells, and then the wind brought even new smells too. And then, Brigitte said, maybe an hour later, she saw something she couldn’t believe. Jep Jep’s ears had pricked up and she was standing and her head and neck had arched a straight arrow toward the moon. And suddenly, she didn’t look 15 or 16 or 17, but a puppy; she let out a howl; her eyes rolled, and she ran.

16

And so her legs worked, again, and continued working during those final years, that time period where she, absurdly, had begun approaching us not from the front, but the rear, when she would back into us in a sort of grinding motion, wiggling her bottom against our legs, doing whatever she wanted, the way people, though especially the elderly, do after they stop caring about what other people think. But this too was a period of cheese, lots of cheese; in the evenings she no longer ate kibble or canned food, she was beyond that now, and so she ate what we ate: chicken, spaghetti, sausages, but, like my grandfather, who was ninety-four, and who would sneak downstairs in his own home in Canberra to down packets of sugar and nibble on cheese blocks from the fridge, it was the cheese, I’m sure, that my father fed her that kept her living so long. How old was she? It’s hard to know. At times, she was eighteen, at others, twenty-one, but after a certain point, I just told people she was twenty. Oh my God, look at her! students, though generally girls, from QUT would say as my mother and I walked her slowly around the campus. Inevitably, they would crouch to pet her, and we would tell them to approach from the front, to let her sniff their hand, not because she was aggressive, but because, at the age of twenty, she had become deaf and blind.

17

In a sense, I had returned home that summer because I was blind too. I was twenty-five and had suffered a ten-month migraine that left me dependent, or mostly dependent, on others, unable to look at books, a phone or a computer, the things up close, anything with a screen, and in those early months of 2016 I would lie, once more, on the floor next to Jep, our beautiful girl, both of us, suddenly, no longer adults, but helpless, children. Dad would keep track of Jep’s deworming schedule, hiding, when necessary, those pills she hated in her chicken, her treats, while Mum read to me from Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic, that book I loved, not because of the content⎯I was, pathetically, too proud for that⎯but because it was the first book I had heard in as long as I could remember. The pain, then, was sporadic, occasionally horrific, but during my recovery what I remember most is Jep Jep and how my father washed her and held her and rubbed cream into her bald, rashed skin; I remember the car trips that Mum and I went on to Mt Cootha, Jep Jep in the back, and how we spoke about pain: what to do with it, how to treat it, as she said, like a friend. At the time, that phrase angered me, seemed inconceivable, but now, nearly six years on, I think, maybe, I am beginning to understand. Without that pain I wouldn’t have had this essay; I wouldn’t have returned to Brisbane; I wouldn’t have been able to spend those last months with Jep, my family; I wouldn’t have been able to say goodbye.

x

18

x

Her last meal was spaghetti. I had returned to Sydney, attempting to resume a life, a writing life, I was no longer sure I wanted, when I got the call. We were on speaker-phone, and Mum and Dad told me that her kidneys had started failing, that she had been put on pain killers, that she had stopped barking, that once again she could barely walk. At the vet, they draped her in a green blanket and my parents held onto her back, her paws. And so she went, I heard, like she came: quietly, but also differently: peacefully, and, I think, I hope, no longer alone. And if this really were a eulogy I would wish only to conclude like this: that she was a girl who had known suffering, true suffering, but that miracles were still possible, that our bodies could fail and start working again⎯she had proven, at least to me, that it might be possible to start over, to feel okay, to learn to love and trust, uncompromisingly and wholeheartedly, again.

x

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Oliver Mol is the author of Lion Attack! He has published over 60 works in Australia and overseas. Rolling Stone called him: King of a New Jungle. He is working on his second book.