Post (mortem) cards #3: Who Can Be Against Us?

By Chloe Wilson

Headline writers seem to find toilets irresistible. Search for the Faggiano Museum in Lecce, Puglia, and the title of every result will mention that its existence is owed to a broken toilet and one man’s obsessive quest to restore functional sanitation.

The story is true: Luciano Faggiano bought a property near the town’s Roman ampitheatre with the intention of turning it into a trattoria. However, sewerage kept backing up. Faggiano therefore began to search for the broken pipe which was causing the problem.

In doing so, he inadvertently began a full-scale clandestine archeological excavation.

He told neither the neighbours — who became suspicious when loads of debris started to be carted away from the property — nor his wife, who he thought would disapprove of his lowering their twelve-year-old son, Davide, into the site’s least accessible areas with a rope around his waist[1].

By the time authorities were involved, the site’s importance was becoming clear. There was evidence it had been occupied by Messapians over 2,000 years ago, and had been used for a variety of purposes since, a Roman granary and a Franciscan convent among them.

The Faggiano museum contains some truly astonishing things: a Roman cistern you can enter via a precarious spiral staircase; a “dead dryer” — a deep pit made of stone where corpses were left to decompose until they had dried out; etchings which suggest the presence of the Knights Templar; remarkably vivid Majolica tiles; and a disproportionately high number of escape tunnels, believed to lead to the ampitheatre nearby.

But a sense of discovery-fatigue has settled over the museum. Apparently, over 5,000 archaeological items[2] have now been uncovered. Many are scattered willy-nilly in glass cabinets with little information or context. A sign informs the visitor that there are many many more fragments held by heritage authorities.

There is also a palpable sense of the owner’s longing for the trattoria that never was[3]. On the upper floor is a kind of ghost version of his dream: one room contains an abandoned, dusty bar (glass fronted and full of junk); another a dining suite, along with display cabinets of wine; elsewhere there are seemingly random articles of furniture, a gramophone, and an assortment of knick-knacks. It’s not clear whether it’s resentment, fatigue or a lack of funds that has led to this odd assortment of items occupying an archaeological museum. But it does rupture the atmosphere of ancient mystery somewhat.

For instance: the room in which my favourite artefact was placed. This was a space filled with rows and rows of chairs with dusty floral cushions — ready for an event that concluded a long time ago or perhaps was never scheduled to occur. The result of this bizarre and claustrophobic overcrowding is that a truly striking thing can easily be missed.

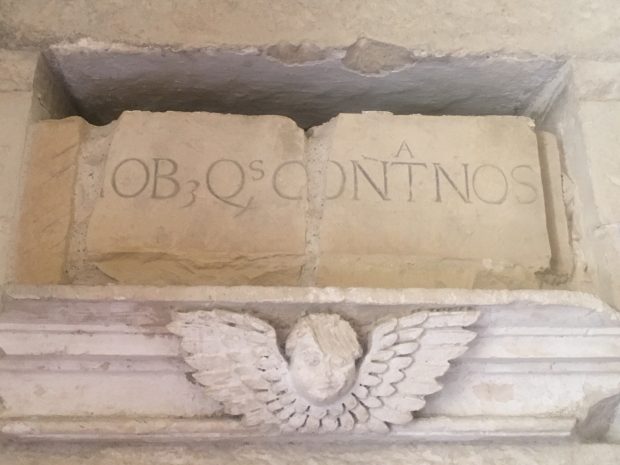

This object — now wodged into a wall — is part of a stone tablet which would have sat above the door of the Franciscan convent which once occupied the site. It bears an inscription all visitors would have seen when entering:

Si Deus nobiscum quis contra nos?

Meaning:

If God is with us, who can be against us?

This is a piece of scripture (it’s from Romans 8:31). But part of the tablet is missing. What remains is an abbreviated version of ‘nobiscum quis contra nos’. That is to say, God has been taken out of the equation.

I enjoy the veiled threat in the original biblical quotation. It gives the sense that God is a kind of strong-armed protector, the nuns’ muscle; perhaps the function of the sign was to make a potential invader (and Lecce, with its key geographic position in the heel of the Italian ‘boot’, has known a number of invaders) think twice before entering.

There is also something in the tone of it which recalls one of the stories about St Clare of Assisi[4]. The story goes: when the soldiers of Frederick II arrived to plunder Assisi, Clare went out to meet them, armed only with the blessed sacrament (consecrated bread and/or wine). She knelt to pray; the soldiers fled in fright. For this reason, two of her most recognisable attributes are the monstrance and the pyx.

It is the ambivalent half-inscription, however, which became the subject of a poem. I was drawn in by the remaining words; by the way they no longer suggest piousness or faith, but rather a degree of braggadocio. There’s a throwing-down of the gauntlet in asking ‘Who can be against us?’ — a claim to power in the certainty, the invulnerability of it.

Then again, there’s a hint of this latent violence in St Clare’s totem objects, too. A monstrance contains incense and a pyx is a container for the consecrated host. But how closely do the words suggest terror and weaponry: a monster monstering, an axe or a pick?

I’m aware that this is a quirk of English and other languages (or other translations), might suggest something quite different. Nevertheless, one wonders about the nuns, with their escape tunnels and their death dryers. One wonders how the stone with God’s name on it came to be destroyed.

[1] Yardley, Jim. “Centuries of Italian History are Unearthed in Quest to Fix Toilet”. New York Times. 14 April 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/15/world/europe/centuries-of-italian-history-are-unearthed-in-quest-to-fix-toilet.html

[2] “Museo Faggiano”. Atlas Obscura. nd. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/museo-faggiano

[3] Apparently Faggiano has bought another building elsewhere, so the longed-for trattoria may still materialise.

[4] St Clare of Assisi was the founder of the ‘Poor Clares’, the Franciscan order of cloistered sisters to which the Lecce nuns would have belonged.