Post (mortem) cards #4: Hodie Mihi, Cras Tibi

By Chloe Wilson

I attended Catholic schools and went through all their various rituals: dreaming up things to confess to our sleepy parish priest; allowing communion wafers to adhere to my palate; flicking through hymn books to find the most amusing hymn to request during singing practice in the chapel (the winner was typically ‘God of Abraham’, as it had seventeen verses and we all liked to see if the choirmaster would endure the entire thing[1]).

But no-one ever attempted to describe the afterlife to us. It was tacitly agreed that there was one, and that God’s huge eye could peer into our skulls at any moment to assess the worthiness of our thoughts on homework and lunch. There was no effort made, however, to indicate what might happen to us after we died.

The only person to ever say anything explicit on the subject was a substitute teacher I had in grade prep. Her name was Mrs McSweeney. She had a bowl haircut and wore thick beige tights. One day, apropos of nothing, she announced to the class that “Hell is eternal loneliness”. That remark chilled me. To be frank, it chills me still.

Anyway — given that no-one was game to describe heaven, it is perhaps understandable that tackling purgatory — still a part of Catholic doctrine — was out of the question. Confusion has abounded for centuries about what it is (a ‘spiritual state’, rather than a physical locale, is how church authorities describe it) and how to get out of there. I emerged from thirteen years of Catholic education with a vague notion that it functioned as a kind of spiritual mangle, taking soiled but not unsalvageable souls and wringing them until they were fit to be in the presence of the Almighty.

Artists depicting purgatory have tended to favour the idea that such souls will only be cleansed through flames of purification. Most paintings of purgatory thus seem indistinguishable from representations of hell (except that there are often saints and angels bailing people out): there’s fire, there are rivers of lava, and there are demons — winged, toothy, some moustachioed, others doggish or goatish — undertaking the traditional infernal torments (prodding, tearing, leering, mindlessly snacking on souls).

The apprehensive venial sinner might be comforted by other representations — Gustave Doré’s illustrations to accompany Dante’s Inferno show purgatory as a shady sort of picnic grove where souls can writhe in relative comfort, while Mateu Lopez’s 16th century Bridge of Purgatory resembles a popular hot springs resort.

Nevertheless, the overwhelming message seems to be that purgatory is best avoided. Churches dedicated to purgatory — or perhaps to avoiding it — are relatively common in southern Italy. The reason for this is neatly summed up in an article on Atlas Obscura:

After Protestant pushback on this concept [purgatory], Catholics reiterated the importance of the doctrine. A concrete result of this reaffirmation was the construction of several “purgatory” churches around southern Italy and Sicily, where mass was celebrated to pray for the souls of those in limbo, so they could go on to heaven[2].

One purgatory church that stands out is the Chiesa Santa Maria del Suffragio in Monopoli. This church — located on the cheerily signposted Via Purgatorio — is famous for two things. The mummified bodies of several founding members, which hang from one wall of the church dressed in purgatory-themed outfits. And the door: an imposing black structure flanked by a decorative border of carved stone.

The door comprises 22 panels; of these, the largest two each contain a skeleton holding what seems to be an unfurled scroll — they might be conferring over the names of those destined for purgatory.

In the other panels there are symbols of various occupations: a bishop’s mitre, a selection of trade tools, a knight’s plumed helmet. The inference appears to be that no rank of person, however rich or powerful, will escape eventual judgement.

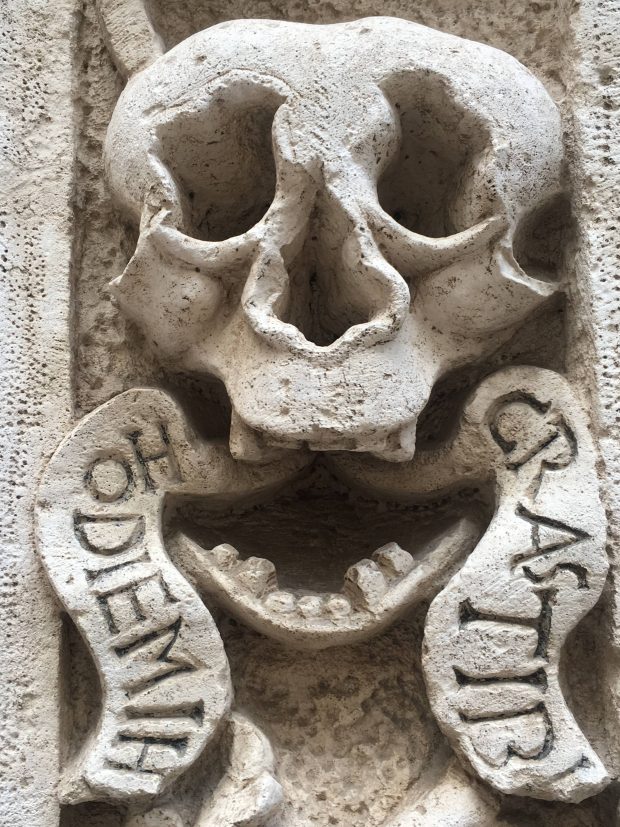

The carved stone border is festooned with foliage and flowers, and is studded with a number of skulls. One has its mouth open, and a banner clutched between its jaws, on which is engraved a Latin motto with which I was unfamiliar: Hodie Mihi, Cras Tibi.

Or: Today it’s me, tomorrow it’s you.

This phrase is synonymic with Memento Mori; another way to remind passers-by that life is fleeting. But there’s something unusual about the tone of ‘Hodie mihi, cras tibi’. It’s snappy. It’s almost taunting. There’s a vague whiff of #yolo about it.

Moreover, the skeletons and skulls on the door of Chiesa Santa Maria del Suffragio seem anything but dead. They’re expressive, lively, animated. As such, they don’t seem totally compatible with the idea that the body returns to nothingness while the (judged) soul is eternal.

This incongruity is what I wanted to capture in writing about the door, and its carved words of warning: these things are intended to enforce the idea of purgatory, but inadvertently undermine it. The skeletons seem part mortal, part immortal — they’ve shed most but not all of their bodies, and it’s not clear whether they’re in heaven, hell, purgatory, or have been given some sort of administrative position in the afterlife’s doubtlessly vast bureaucracy.

Because of this, I find that there’s something oddly reassuring about them; about the way in which they betray the church’s certainties. ‘Hodie mihi, cras tibi’ might seem a taunt, a warning, a threat — but it also reads like a promise, or an invitation to an exotic destination which all souls, mangled and unmangled, are eligible to enter.

[1] He did.

[2] “La Chiesa del Purgatorio”. Atlas Obscura. n.d. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/la-chiesa-del-purgatorio