A Short History Of Reading

by Moreno Giovannoni

John Clarke, who died a month ago, said it:

Our minds were on fire at that age.

He was talking about the creativity he discovered in himself when he went to university. In my late teens and early twenties which is more or less the age he was referring to, my mind was “on fire” too, except that I became hungry to absorb knowledge and ideas and if anything create a world view for myself.

When it came to reading fiction (and non) for me it had an unusual beginning and then continued more or less on an unusual trajectory.

For this post I have thought about the books I read in my teens and early twenties and have briefly mentioned them and what I remember about them, without looking at them. I wanted to discover what I remembered of a novel, a book of stories, twenty-thirty-forty-years later and to recall the impact it had on me. I found I sometimes associate a particular special book with a time and place.

Before I begin, just a thought: books are not just books, although they all have covers and pages and numbers on the pages. Some books are about cooking and cricket, cooking and love, cooking and Tuscan gardens. Some books are like packets of chips. And some people read novels as if they were eating chips. Crunch crunch crunch. Next. Crunch crunch crunch. Next. For them reading is consumption, the reading brain is the intestine. The last page, the back cover, is the bowel. The bedside table becomes the pantry.

But some books are not like chips.

***

My mother and father, bless them, said I was a child prodigy. At the age of five, in Whitfield, in the King Valley, I would read the local Italian newspaper to my uncle who hadn’t done well at primary school.

For my ninth birthday my grandfather Giuseppe, a.k.a. Bucchione, sent me, from Italy, the Adventures Of Robin Hood – in Italian. So, imagine that: a nine-year-old boy living on a tobacco farm at Buffalo River in north-east Victoria, attending Grade 4 in a Catholic school, was given to read a book written in Italian.

It arrived in a parcel wrapped in brown paper with lots of sticky tape around it and funny handwriting on it that wasn’t Australian. It was cursive and like the handwriting in the aerogrammes my mother received from my grandparents.

Not only was the handwriting different to what I was used to, the book itself didn’t look like any book I had seen. It was a soft cover, larger format than I was familiar with. I had never read a whole Italian book before. I waited a few months before having a go.

Then when I was into it I slogged away at it, laboriously, determined to finish it. The more I read the less laborious it was and then I started flying. It was exhilarating, to be reading a book in a language other than English.

In this book Robin Hood and Little John grew old and Robin Hood died. This was shocking. I don’t think I had read a book where the hero grew old and died. Until then I had been feeding on a diet of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five books, Marvel comics and The Phantom.

I remember a dramatic moment towards the end when Robin Hood shoots an arrow out of the window of the room where he is dying. He asks Little John to bury him in the forest where the arrow lands. Even now I am overwhelmed by the feeling of sadness I felt then.

This early emotional experience of reading in Italian was to have a major impact on my reading life. It gave me the confidence to later read in French. It also showed me that here was more to the reading world than books written in English.

***

A year of going to school in Italy at the age of fifteen forced me to write and read in Italian. At some stage I read for the purpose of study for the first time, I promessi sposi, the classic nineteenth century novel by Alessandro Manzoni.

Back in Australia, in Form 5 the nuns would send us to the local library, a short walk from the school, to browse the stacks, return books and borrow new ones. They were encouraging us to read. I became an expert at scanning grown up fiction for salacious paragraphs. I also picked up Thomas Hardy’s The Trumpet Major about which I remember nothing at all.

I read a lot of science fiction as an adolescent. I remember some classic authors: Asimov, Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke. For a while in my late teens The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus was my most well-thumbed book.

In those days, my Catholicism having lapsed, I think I was looking for an intellectual and emotional substitute and found it in art, literature in particular. Years later the search would manifest itself in visits to museums and art galleries, and attending operas and MSO performances. For a while I even collected opera houses (Melbourne’s State Theatre, Sydney’s Opera House, Verona’s Arena, Venice’s La Fenice, New York’s Metropolitan Opera House). I still have my sights set on more Italian opera houses, as well as Covent Garden.

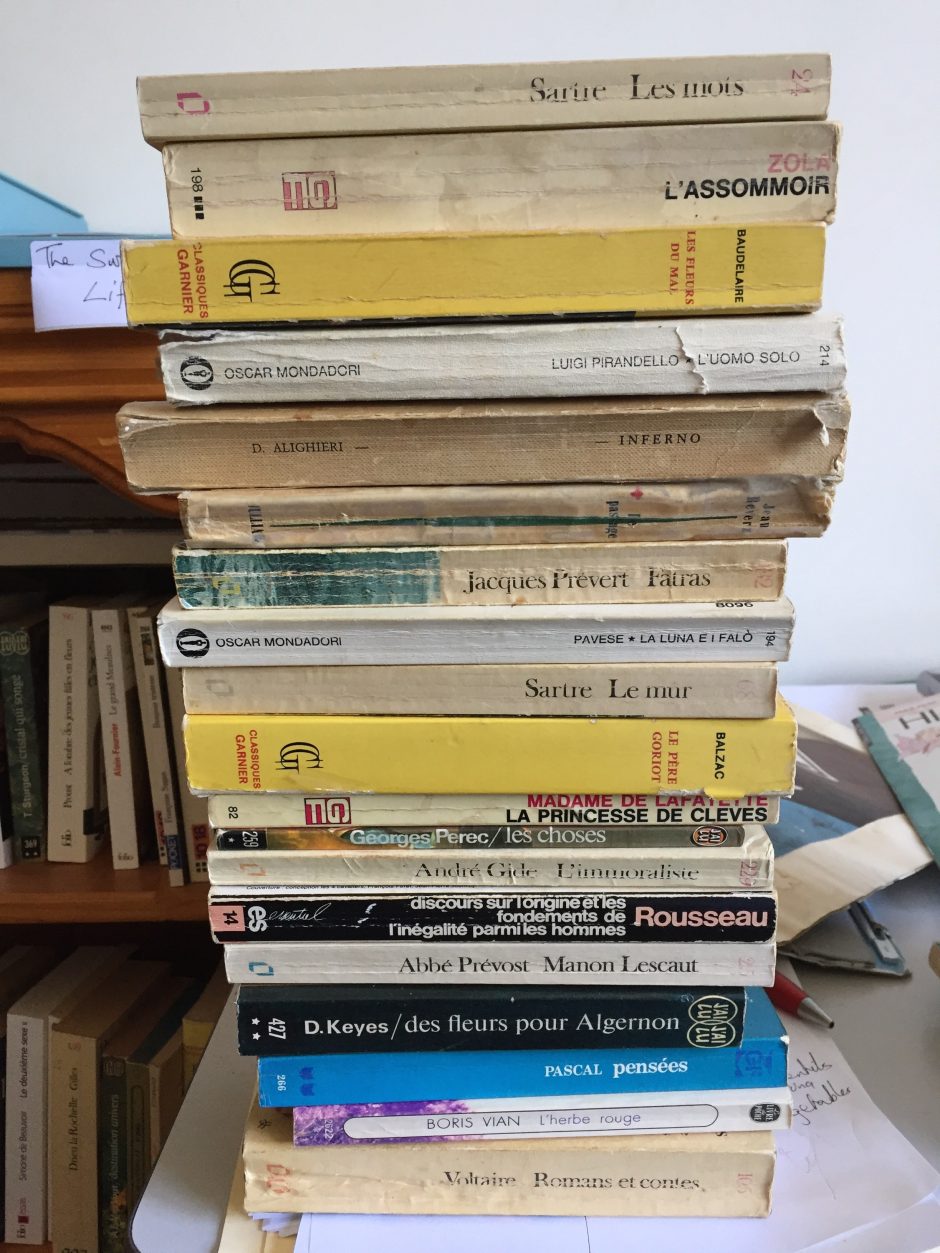

Reading Crime and Punishment at the age of 17 was perfect. Fyodor Dostoevsky took me on a tour of Raskolnikov’s human heart like nothing else since. I then read Chekhov’s stories, Tolstoy (Anna Karenina and The Death of Ivan Ilyich, not War and Peace), Turgenev (I fell in love with Asya), Flaubert (I fell in love with Emma and hated her aristocratic lover, although I felt sorry for her boring husband), Pavese (in La luna e i falò I understood the sadness of the successful migrant who returns to his Italian village and sees what he has lost), Tomasi Di Lampedusa’s Il gattopardo (and how everything must change for everything to stay the same), Sciascia’s fascinating insights into the society in which the mafia flourished, Camus (La chute, L’Étranger, Le mythe de sysyphe) and Sartre (I thought La nausée was about me. For those in the know, there was a Printania restaurant in Glen Huntly years ago).

I knew that although it was pretty important, the literature of the anglosphere was not all there was. Australians probably forget that, if they ever knew.

Nevertheless, of the English books Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles taught me how cowardly men are and how cruel fate is. At the age of nineteen I loved Jean Rhys who, I will ashamedly confess, I felt wrote like a man. Until I discovered Margaret Attwood, and she did too.

I read for knowledge. I read to learn about the human condition. That expression, the human condition, to me in my late teens and since has meant the condition of knowing that you are alive and will die. And only human beings know that. Since then I have seen it used to refer to the ordinary travails of life and wonder if I got it wrong at the time. The human condition to me is not about work, family, ambition, power, lust, greed, love etc.. It is simply the knowledge of our own mortality.

In the final year of high school in Australia, because we didn’t have an Italian teacher a few of us studied Italian as a subject without regular classes. The novel we were studying was Il cappello del prete (The Priest’s Hat) and I remember reading it and writing a three-page summary of it in English for some of my schoolmates. I made multiple roneoed copies. I can’t remember the author or what it was about.

After high school I went to Italy to start my university studies in Pisa where I was studying French, English and Psychology.

This meant reading Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe, about which all I remember is the character of the protagonist, a young man who seduces an older woman and then is unable to easily extricate himself from the relationship. Adolphe was the entire Year 1 French course. It satisfied my need to learn about human behaviour.

For the examination, seated at a table in front of three university teachers, I had to be able to read excerpts from the novel, discuss it and translate a section into Italian. The examination lasted 40 minutes while a room full of students waiting their turn stood behind me and watched and listened.

While hitch-hiking and catching trains in England, France and Italy I read a collection of Voltaire’s writing called Romans et Contes. This book I found while working at a holiday job in Lannemezan, in the Pyrenees. We were collecting unwanted household goods and this was a book someone was throwing out. From Voltaire’s collection I can only remember the famous Candide, and the idea that we all have to get on with life anyway, despite all the fancy talk, and “cultivate our garden”. I liked that philosophy. I also enjoyed reflecting on Dr Pangloss’s idea that we live in the best of all possible worlds.

Another book that was being discarded during the household goods collection was H. G. Wells’ The History of Mr Polly. I enjoyed it a lot. It is about a man whose wife ‘s cooking gives him indigestion so he leaves her and finds fulfilment.

***

It is possible that the book that had the most impact on the young me was The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer. I was staying in Lyon, France, and borrowed a copy in English from a large public library. I read it straight through in two sittings in my little attic room, which I rented from Madame Clape, on the fifth floor above a small supermarket, just opposite the cable car terminus in the old part of the city high up on the hill.

Recently there has been a public discussion about feminism, with statements flying around on social media about “why I am/am not a feminist,” partly stirred up by Jessa Crispin ‘s book, Why I Am Not A Feminist: A Feminist Manifesto. The Female Eunuch did not make me a male feminist. I was nineteen years old and what it did was teach me about the forces that society unleashes on us. Beliefs and “truths” about women, men too, people of various skin tones, were not truths but culturally imposed. From memory, Germaine did not intend her book for women only. She was telling the men too that the system was screwing everybody.

I realised after I had read The Female Eunuch that if they (they?) could do it to women, then they (they?) could do it to anyone. They could label me, black people, brown people, fat people, skinny people, and apply pressure either to make me behave how they wanted or expel me or embrace me. The day I finished reading the book I didn’t become a feminist but a non-conformist. I wasn’t about to behave the way everyone wanted me to behave. The way I saw it, the eunuch wasn’t just female. We men were being castrated too.

Refusing castration meant caring for the people who were close to me, making sure that, in whatever way I could, I would support them in living their lives the way they wanted. It meant I would one day work for myself as a translator. It meant I would not conform to the idea of manly behaviour that involved drinking beer, following the footy and driving a souped up V8 Monaro/Ford/Torana (take your pick). I read French and Italian novels instead.

The author who helped me apply what Germaine Greer taught me was Albert Camus.

Of Albert Camus’ L’étranger I remember a somewhat tortured anti-social protagonist, Meursault, who snubbed his nose at society and lived his life his own way. The name reminded me of “meurt seul” – dies alone. If you were antisocial you most likely would die alone. I remember too the character’s sexual jealousy, which was something I also experienced very strongly.

Having lapsed from my childhood Catholicism I was probably looking for a set of principles by which to live. Once Germaine Greer had pulled the rug out from under my young white male middle class patriarchal feet it was Albert Camus who helped me pick myself up and go on.

In L’Étranger and Le mythe de Sysyphe, the idea was that in a world which has no meaning you just have to construct your own meaning and live by it, and keep pushing the rock up the hill, and just when you think you’ve arrived at the top it rolls down again and you follow it down and then you start pushing it up again.

You don’t follow the crowd. You do what Germaine and Albert suggested.

Hemingway was a favourite in my early twenties. He was a tough guy who wasn’t as tough as he pretended to be. Henry Lawson, who was funny, left me with that Hemingway impression too. I will always associate Hemingway with my youthful plan to fly one-way to London and from there go to Amsterdam to join the merchant navy. Just the kind of thing a Hemingway (and a Joseph Conrad) man might do. It was while I was crossing Faraday Street in Carlton, walking towards the Student Travel office to buy the airline ticket, that it dawned on me how vulnerable his tough guy male characters were.

A writer I loved, in my top four for impact (with Germaine and Albert and Ernest) was Luigi Pirandello. Luigi set out to write a story for every day of the year and got to about two hundred and fifty. The stories are funny, sad, full of pathos, bathos, lonely people, sad people, human beings. I wanted to be him.

In the mid seventies I was just working my way through David Ireland (The Unknown Industrial Prisoner and The Glass Canoe) and into Gerald Murnane when I stopped. David Ireland was writing about the enslavement of the human race. The thing that was memorable about Gerald Murnane was that he could write in detail about a footpath or nothing much and make it interesting.

I think the last Australian book I read in my intense reading phase was Pieces For A Glass Piano by Gerard Lee.

Orwell’s “minor” novels (as well as his essays) I enjoyed and implemented: Coming Up For Air and Keep The Aspidistra Flying. In the first the male protagonist is crushed by married life and the monotonous drudgery of work. I had just got married and was wondering whether that would happen to me. It didn’t. In the second the protagonist in the end gives up his idea of being a writer and writes advertisements instead, to pay the bills and support his family. I did the same. I also grew an aspidistra in a pot in our living room.

I read in the Baillieu Library one day that the novel had been replaced by sociological and psychological analysis and that it was therefore redundant. I think I still believe that.

***

I stopped reading fiction when we had children and a mortgage and I got a day job which occupied the next thirty years of my life.

Since my mid-twenties I have read in fits and starts. For twenty years I read no fiction, preferring history, politics and biographies. I still wanted to learn about the world but felt that what fiction had taught me between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five I now had to find elsewhere. When I did read fiction it was not the usual Australian realism. Some memorable books were Jean Rhys’s, Good Morning, Midnight (1939), Margaret Attwood’s Wilderness Tips, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. I did have a Philip Roth phase a few years ago, probably because I was starting to feel I was approaching the age of his male protagonists and had the same issues to deal with. Of the Arabian Nights I loved How Abu Hasan Brake Wind, about a man, the course of whose entire life is determined by the fact that he farted on his wedding night.

I am now sympathetic to the view expressed by David Szalay in The New Yorker, (October 10, 2016)

I sat down to think about writing a new book and just didn’t see the point of it. What’s a novel? You make up a story and then you tell that story. I didn’t understand why or how that would be meaningful.

As a reader of fiction, that’s how I feel. As a writer I feel like that too.

***

Books have been an important part of my life. I have loved browsing the shelves in bookshops and buying books, even at one stage, for many years, buying a book a week. It has been a kind of fetish.

People who don’t read books think if you have books on your shelves that you have read them all. In my case I have read some of them and intend to read some others. Some I have never read and lost interest in and eventually they will be culled. Some I must keep for my own peace of mind, either because I have read them and want to be reminded of the experience or because they represent something I want to learn about one day.

Meanwhile, has there ever been a more beautiful line written than the final words of Dante’s Inferno?

e quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle

To appreciate the beauty of that you will need to learn to read Italian.