Ardent Dentists and Artists’ Cupboards: Raymond Roussel and Gerald Murnane in Days of Heaven

by Luke Beesley

John Ashbery apparently went into a bookshop in Paris in the late 1950s and said something along the lines of what’s the craziest French writing around, and the shopkeeper had no hesitation in handing him a book by Raymond Roussel (1877-1933). Ashbery brought Roussel’s writing back to New York and showed his friends and not only did they sit wide-mouthed as they imagined the temerity in Roussel’s commitment to a beautifully strange literature, they named their new poetry journal after one of his novels – Locus Solus. Ashbery and Schuyler later went and wrote a collaborative novel, Nest of Ninnies, which was surely inspired in some way by the shenanigans opened up by Roussel’s programmatic approach to plot generation (also, the main character, Marshall, shares the name of the lead in Locus Solus). Ashbery and Schuyler wrote the novel over many years, initially taking turns, writing one sentence at a time. It’s a very funny odd novel. I read it twice. On the surface it’s a chaste 1950s family not-quite-comedy drama, but it’s all a bit sideways-peculiar; as if some of the adjectives in the book, and some of the verbs, had been freed to swap places with other verbs and adjectives elsewhere:

“Oh, dear—what a morning it’s been,” she said placatingly to Alice, flourishing a large flashlight.

If you want to know all about Roussel, though, read the brilliant Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams by Mark Ford, the Ashbery scholar, who was also giddily distracted by Roussel when he came across him via Ashbery. It’s easy to get sidetracked by Roussel’s bizarre eccentric life (where to start? Extreme inheritance eventually blown, over the years, on obscenely luxurious mannered lifestyle and the production and self-publication of all his own books: poetry collections, novels and plays he presumed were accessible and masterpieces but turned out to be appreciated by hardly anyone while he was alive, other than the surrealists, who tried to embrace him. Theatre productions of his plays – which were very long and ridiculously linguistically dense, were a circus: half the audience would begin to yell insults at the stage, the other half – the surrealists – would begin yelling at the patrons. The plays soldiered on farcically) and there’s enough of that in the book, but Ford also holds focus on Roussel’s delicious processes…

You may be familiar with all this but it’s fun to revisit. In a sort of disappointed big reveal, Roussel wrote How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935) a posthumously-published essay explaining the details around his procede, of generating sentences and narratives which revolve around very specific and intricate punning.

For example, Roussel’s early short stories began and ended with almost identical sentences that could have completely different meanings. The following, taken from Mark Ford’s translations, is an example. In the short story, ‘Parmi Les Noirs’, the beginning sentence is: “Les lettre du blanc surles bandes du vieux billard” (“The letters [as of the alphabet] in white [chalk] on the cushions of the old billiard table”). This story ends: “les letter du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard” (the letters [missives] sent by the white man about the hordes of the old plunderer). The attempt to arrive at the second meaning of the sentence by the end of the story would provide Roussel with his narrative, one that often required surreal funny extraordinary shifts and flexes to arrive at its companion sentence. (Ford 1-2)

Or a sort of flipside – Roussel would find two sentences that sound similar but are composed of entirely different words, and begin to generate narratives out of the differences – don’t try it at home. Oh, ok, I’ll give it a go…

Sargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band: Ardent dentist, only ours, out clubbing! / Sars interprets only arts love and… / His ardent pepperoni, ants climb hand… /An ardent pepperoni eski bind. / This ardent pepperoni arts climber. /Ardent pepperoni! Artist cupboard! / Sardonic pepperoni artist cupboard. / Large ant pepperoni artist cupboard. / Large ant pepperoni arts love-in?

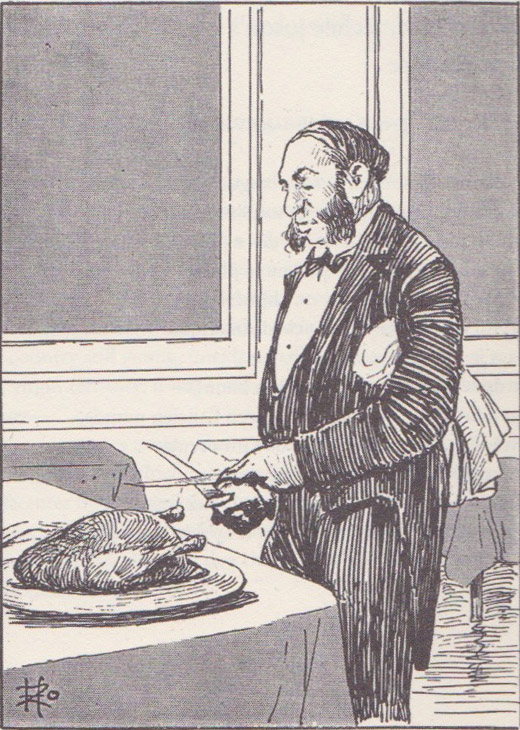

Roussel’s long poem, New Impressions of Africa (1932), has a mind-boggling parenthetic structure (four long sentences stretched over hundreds of pages), with footnotes, requiring gorgeous strange surprising leaps to hold it together, not to mention ((((((((incredibly deep parenthetic levels indicated by multiple))))))) arrowless archer bows. Reading the poem you try hard to hold to the logic of the previously broken sentence, but the ship sails away, only to have the memory vaguely jolted again, seasick, hitting your head on a low beam. Perhaps one of the most haunting and brilliant aspects of this collection is that it is accompanied by illustrations that Roussel anonymously commissioned via a detective agency. He left the artist, Henri-A. Zo, with succinct instructions for each drawing e.g. “A mountaineer admiring the view in some high place (ecstatic posture).” Or, as in the picture somewhere in this blog entry: “A waiter with a pair of crossed knives that he is using to carve a roast chicken. No other people.”

Zo was apparently pissed off when he eventually later found out that the drawings were for Roussel. It’s fun to notice Zo straining to respond to a broad mystery audience, rather than letting his hand go wild and free for the latest Roussel novel.

(I spent quite some time on the couch trying to draw Roussel, and was joined by my 6-year-old son. As usual his first attempt was spot on, and he happily let me use it for this piece.)

In Roussel’s novel, Impressions of Africa (1910), every sentence’s possible puns and sounds work to continually offer him stimulus for future sentences and narratives by way of a constant check for double meanings and alike-sounds and punning in the sentences he was presently writing. The previous sentence in itself goes to something in the writing of our own Gerald Murnane. The meta-sentence “While I was writing the previous sentence…,” appears in many of Murnane’s novels. In fact, his most recent novel A Million Windows came out in the middle of a twenty-three course meal. Or it took less than a minute to read through the details but the meal apparently went for most of the morning. Roussel did this reguarlly, beginning with a chocolate soup and moving through to Oxalis (wood sorrel) a la crème. Murnane I’d imagine would have none of it, preferring something like steak and two veg. They would eat differently, surely, but they both travelled eccentrically (Murnane, of course, still does). Murnane famously has never been overseas, and has rarely left a small area beginning in the inner north of Melbourne, and moving out a little to North-West country Victoria. Roussel, on the other hand, travelled all over the world, including a trip to Melbourne, and yet he seldom moved past his own exotic fantasised expectations of place: he travelled to meet his own imagination, and spent much of the time “travelling” inside his purpose-built campervan home. Murnane didn’t bother with

In Roussel’s novel, Impressions of Africa (1910), every sentence’s possible puns and sounds work to continually offer him stimulus for future sentences and narratives by way of a constant check for double meanings and alike-sounds and punning in the sentences he was presently writing. The previous sentence in itself goes to something in the writing of our own Gerald Murnane. The meta-sentence “While I was writing the previous sentence…,” appears in many of Murnane’s novels. In fact, his most recent novel A Million Windows came out in the middle of a twenty-three course meal. Or it took less than a minute to read through the details but the meal apparently went for most of the morning. Roussel did this reguarlly, beginning with a chocolate soup and moving through to Oxalis (wood sorrel) a la crème. Murnane I’d imagine would have none of it, preferring something like steak and two veg. They would eat differently, surely, but they both travelled eccentrically (Murnane, of course, still does). Murnane famously has never been overseas, and has rarely left a small area beginning in the inner north of Melbourne, and moving out a little to North-West country Victoria. Roussel, on the other hand, travelled all over the world, including a trip to Melbourne, and yet he seldom moved past his own exotic fantasised expectations of place: he travelled to meet his own imagination, and spent much of the time “travelling” inside his purpose-built campervan home. Murnane didn’t bother with  the actual travelling, needing no prompting. Roussel was anxious for a little imaginative prompt, whether it came from the sentences themselves or a game or a trip or structure. In what I imagine as a scene from Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven – that majestic, archetypal house in the middle of endless grasses – Murnane in A Million Windows looks out from a room on the upper floors into the fields and back into the future of his narratives, building them from his own memory, the rooms of the house and his own act of writing and his own actual writing and his own actual characters or first-person narrators who are very much like himself but at other angles or actualities, holed up in other rooms of the same house. Perhaps Days of Heaven was the highlight of Malick’s career? Moonlight on a shallow stream as Richard Gere and Brooke Adams kiss and chase each other past midnight. I had low hopes for Malick’s recent film, which came out last year. I’ve actually forgotten the name of it… Knight of Cups. One of the worst named films in recent cinematic history. As a title, perhaps a little worse than Nest of Ninnies. Ashbery, bringing Roussel to his New York chums. Roussel’s strange writing – the Fellini-like circusy interlude in the middle of Days of Heaven…

the actual travelling, needing no prompting. Roussel was anxious for a little imaginative prompt, whether it came from the sentences themselves or a game or a trip or structure. In what I imagine as a scene from Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven – that majestic, archetypal house in the middle of endless grasses – Murnane in A Million Windows looks out from a room on the upper floors into the fields and back into the future of his narratives, building them from his own memory, the rooms of the house and his own act of writing and his own actual writing and his own actual characters or first-person narrators who are very much like himself but at other angles or actualities, holed up in other rooms of the same house. Perhaps Days of Heaven was the highlight of Malick’s career? Moonlight on a shallow stream as Richard Gere and Brooke Adams kiss and chase each other past midnight. I had low hopes for Malick’s recent film, which came out last year. I’ve actually forgotten the name of it… Knight of Cups. One of the worst named films in recent cinematic history. As a title, perhaps a little worse than Nest of Ninnies. Ashbery, bringing Roussel to his New York chums. Roussel’s strange writing – the Fellini-like circusy interlude in the middle of Days of Heaven…

Images: Henri-A. Zo drawing, Days of Heaven poster, A Million Windows cover, and drawing of Raymond Roussel: copyright © Ari Miller-Beesley.