In her pocket she carries her heart

by Natalie Harkin

Some moments linger to leave an indelible imprint on your mind, heart and spirit – they become the memories that rest under your skin, or recur with an unanticipated and uncanny trigger, or like stubborn stains, they simply refuse to fade. This week I’ve been thinking about such moments shared with Kookatha/Nukunu woman Yhonnie Scarce. Pride bursts for my acclaimed glass-artist friend who has just installed a major new work Death Zephyr in The National 2017: New Australian Art exhibition that opened last week in Sydney. Yhonnie’s work is an embodied response to the ongoing fallout from nuclear bomb tests undertaken by British and Australian Governments at Maralinga, South Australia, between 1953 and 1963. This human rights abomination should be listed as a crime against humanity. Traditional Owners, including Yhonnie’s family, were not informed or protected before, during and after these nuclear bomb blasts. The living memory of Maralinga is as relevant today as it was when people died on, or were forcibly relocated from, their vastly contaminated lands.

Death Zephyr extends another major install, Thunder Raining Poison, conceived and created by Yhonnie for the 2015 Tarnanthi Festival at the Art Gallery of South Australia. Both large-scale works employ over 2000 hand-blown glass bush yams suspended from the ceiling that represent radioactive dust falling from the sky. You could walk so close to Thunder Raining Poison, to almost reach in and catch a trace of the deceptively peaceful fallout. On the other hand, Death Zephyr is suspended high enough to walk beneath and imagine being swept-up in its deathly toxic wind.

I’ve known Yhonnie for nearly half my life, and cheekily like to think she unleashed her artistic flair by helping to paint my little workers cottage bullnose veranda two decades ago! Her work blows my mind. It is also deeply appreciated by my teaching team at Flinders University as a way to affectively teach traumatic histories. Students are indeed transformed by such works and typically respond, why weren’t we told? Teaching ‘policy history’ is a challenge at the best of times, however, engaging works by Indigenous artists like Yhonnie, provides unique insight and depth to hidden histories and stories, like those from Maralinga, and their resonating impact on contemporary life.

I also engage Yhonnie’s work Florey and Fanny (2011) to teach about State-orchestrated systems of indentured domestic labour targeting young Aboriginal girls for removal from their families; once again a history largely unknown, despite it being a significant story in the collective narrative memory of Aboriginal South Australians. For this work, Yhonnie was measured, pinned, hemmed, wrapped and tied into these linen aprons that were made to fit her shape; styled upon those that her Grandmother Fanny and Great-great-grandmother Florey wore when they were domestic servants in the early 1900s. Yhonnie hand-stitched their names into the fabric of each apron, with a patient and contemplative love. In addition, she made sixteen hand-blown glass bush plums that represent her family and childhood memories brought forward, to sustain her; hidden narratives tucked in apron pockets, and a reminder of the need to safeguard and protect one’s body and identity. This embodied work consciously invokes and repeats multiple histories of family and State; of trauma and deep love. These fruits are protected in the domestic apron pockets; tucked away from prying eyes or from people who could take them away.

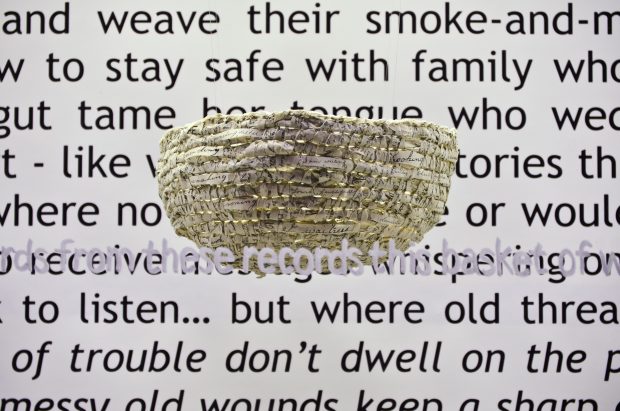

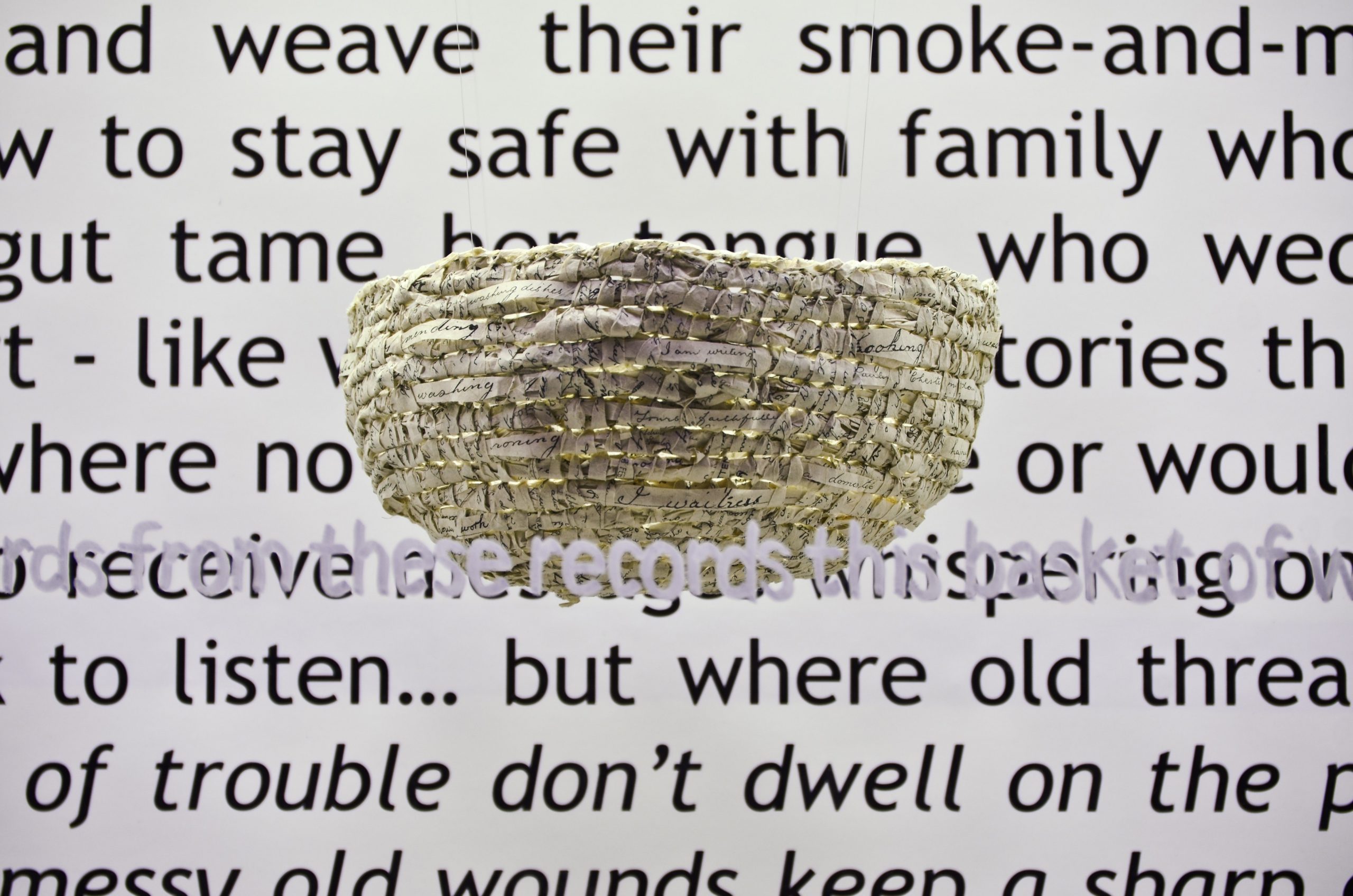

In one of those ‘indelible imprint’ moments, Yhonnie and I were both exhibiting work at the australian experimental art foundation (aeaf) in 2013; Yhonnie was installing Florey and Fanny (2011) in the main exhibition space, and I was installing Archive-Fever-Paradox [1] in the window-box space, curated by Ali Gumillya Baker. I had woven a basket with my Nanna and Great-grandmother’s hand-written letters found on the State’s Aboriginal archives – one way to transform out from the archive-box I found myself trapped in. Like Yhonnie, I come from a long line of Aboriginal domestics and know there is still much work to be done, to clean up this colonisation mess! This archival-basket highlighted key words from my Nanna’s letters to signify her domestic service duties, such as ‘washing’, ‘ironing’, ‘mending’ and ‘housework’. While installing at the aeaf, two additional words were placed into the outer edge of the basket: ‘apron’ and ‘uniforms’, to pay respect to both Florey and Fanny.

Yhonnie called me to her: Come and give the dresses a cuddle. We held one apron each, gently at first and then closer until they were pressed against our bodies; our faces buried in the cotton-linen to capture our scent. Yhonnie pressed hers to her neck, so the fabric could soak up her skin’s oil; the essence of granddaughter infused deep within the linen threads and folds. She carefully slid both aprons onto plain wire coat hangers and hung them on hooks from the wall with gentle and astute positioning. I imagined them hanging from an old washing-line, floating on the breeze and casting shadows as they dried crisp-white in the sun – our Apron Sorrow:

The aprons were then ready for the glass fruits to be placed in the pockets – largely hidden, but acutely present, their stems poked through small hand-stitched holes. They moved slightly, of their own accord, like they were nestling in familial comfort, love and protection. The weight of the fruit in the pockets adjusted the folds of fabric, so the aprons hung with new purpose. We stood back and observed them finally hanging, still and quiet, and let their story unfold.

We then held my basket of letters up to the newly installed aprons, and introduced the four women represented in our work. As mission children, state wards and domestic servants, we imagined our Nannas had most likely crossed paths or perhaps even knew each other, as they had all endured forced placements to missions, government institutions and white homes in South Australia during the same policy era. In that moment, when our poetic-offerings came together, Yhonnie realised it was the first time Florey and Fanny had been shown in South Australia; an emotional welcome home to Kaurna country.

Florey and Fanny have agency to signify something else beyond symbols of servitude and subjection. Despite the glass bush plums being placed into white linen ‘aprons of colonialism’, these fruits are clever and subversive; dignified and defiant. They are our Nannas, our Aunties, our Great-Grandmothers. They are always, and will forever be, firstly, Aboriginal.

Indelible moments… be it serendipitous sharing of the exhibition space, or the spirits of our Nannas conspiring, whatever the reason, we were old friends projecting familiar stories together, in new ways.

I urge you to check out Yhonnie’s Death Zephyr showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales – let it settle to rest under your skin, and never leave you.