Poetic Epigenetics: Bodily memory, silence & community

By Andy Jackson

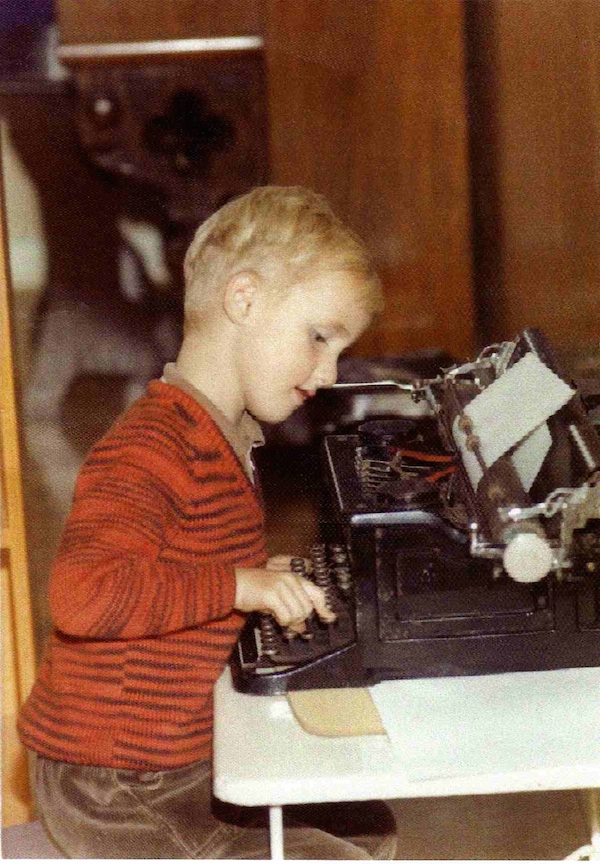

He wears a handmade v-neck jumper, and leans over the manual typewriter, earnest and calm. Four years old, his blond hair seems recently and neatly cut, and his skin looks very soft. He’s immersed in what each push of a single small finger will do to the paper, oblivious to the photographer, or who might see the photo in the future. It’s an uncanny photo, because this is me, but I’m not sure it’s my body.

He wears a handmade v-neck jumper, and leans over the manual typewriter, earnest and calm. Four years old, his blond hair seems recently and neatly cut, and his skin looks very soft. He’s immersed in what each push of a single small finger will do to the paper, oblivious to the photographer, or who might see the photo in the future. It’s an uncanny photo, because this is me, but I’m not sure it’s my body.

What my body is and what it isn’t seems like a pretty straightforward distinction. But perhaps “my body” as a phrase isn’t quite right – it assumes certainty and singularity, yet if we look closer, in spite of the continuity and stability we feel in our bodies, we might detect numerous possibilities, even multiplicity.

Certainly, when I look back at what I’ve written over the years, I can see the inflections and energies of other poets and writers. They course through my body and writing as disturbance and affirmation. And I can’t imagine who I am without recalling them. Think of this as poetic epigenetics. This post will explore a few of these influences, and how they came to become an inextricable part of my makeup.

I spent a lot of time at the University of Melbourne years before I was even a student there. In my early thirties, I’d come to confess quietly to myself that perhaps I was a poet, or at least perhaps I could become a poet. I was studying at RMIT and one of the things I learnt quickly was the benefit of a CAVAL card, which entitled me to borrow from other libraries.

I spent a lot of time at the University of Melbourne years before I was even a student there. In my early thirties, I’d come to confess quietly to myself that perhaps I was a poet, or at least perhaps I could become a poet. I was studying at RMIT and one of the things I learnt quickly was the benefit of a CAVAL card, which entitled me to borrow from other libraries.

I would stroll the dimly lit aisles of the Baillieu Library, stopping often and for long periods, crouching before long walls of books, bending my neck to horizontal to read the titles and names. With almost all of them hardback, I couldn’t judge a book by its design. And as far as I could remember, I didn’t study poetry at school, so I was ignorant of the canon. I was an odd blur of insecurity and confidence; I wasn’t interested in linear literary self-improvement, what I “had to read”. I went on instinct, what snagged my eyes and unsettled my insides. Certain titles reached outwards like young branches keen for light. One of them was Gathering the Bones Together, by Gregory Orr.

The seven-part title poem begins:

The deer carcass hangs from a rafter.

Wrapped in blankets, a boy keeps watch

from a pile of loose hay. Then he sleeps

and dreams about a death that is coming:

Inside him, there are small bones

scattered in a field among burdocks and dead grass.

The poems earlier in Orr’s career were elliptical, brief and almost surreal, yet always carrying a sense that the images point far off to some profound and dark emotional territory. In more recent poems, Orr will focus on more overtly lyrical and even therapeutic themes, exploring language, political protest, love and poetic form. But here he was somewhere in between. When Orr was twelve, while they were walking with their father on a hunting expedition, he accidentally shot his brother. This tragic event haunts the poet and the poem, reverberates through it, with violence, grief and sudden leaps towards beauty.

Part three of the poem reads, in its entirety:

I crouch in the corner of my room,

staring into the glass well

of my hands; far down

I see him drowning in air.

Outside, leaves shaped like mouths

make a black pool

under a tree. Snails glide

there, little death-swans.

I experience the poem as a shadow moving slowly over my shoulder. As I read, I grow cold, sensing another presence, and my heart begins to shiver and race. A strange and memorable image is juxtaposed with plain confession, details are foreshadowed, yet never entirely clarified. The effect of each movement and impact in the poem is slightly delayed. The language is composed and restrained, thin ice over a deep river of unmoving grief. The shadow of the poem moves over me. I turn around to see the body causing it, but find myself looking up into the sun and my eyes sting with the glare.

“Gathering the Bones Together” concludes with a gesture towards an essential and impossible resolution.

The winter I was eight, a horse

slipped on the ice, breaking its leg.

Father took a rifle, a can of gasoline.

I stood by the road at dusk and watched

the carcass burning in the far pasture.

I was twelve when I killed him;

I felt my own bones wrench from my body.

Now I am twenty-seven and walk

beside this river, looking for them.

They have become a bridge

that arches toward the other shore.

It seemed to me then, and still now, that Orr was somehow able to be both unsettlingly honest and richly withheld. The poem brings together our need for speech and our need for silence. It helped me realise that memory, inarticulate and complex, dwelt not only in the mind, but in my muscle, stomach and skin.

There are many different kinds of silence, though. And sometimes silence arrives with an overwhelming force, sudden and ambiguous.

There are many different kinds of silence, though. And sometimes silence arrives with an overwhelming force, sudden and ambiguous.

A dozen of us, all writers, of varying ages, backgrounds and class, sit together in a portable classroom. It’s a mild late summer morning in Boulder, Colorado. M NourbeSe Philip is our tutor. The class is titled “Noise, Silence and the Sacred: Performing Trauma, Ritualising the Archive”. It seems like a lot of difficult ground to cover. I’m in another country, on my own, and feeling under-prepared.

Philip was born in Tobago and studied political science and law in Canada, but left the legal profession in the 1980s to devote more time to writing. Her 2006 book Zong explores a little-known but potent historical event – the deliberate drowning of 150 slaves en route from the Caribbean to the United States in order to collect insurance money. The language in Zong was created entirely from the very brief documentation of the court proceedings, and dwells in a space of breathlessness and ululation, of grief and fractured solidarity.

In person, Philip is affable, warm and open. The first morning of the week-long workshop begins with us singing together and with brief and gentle physical exercise. We introduce ourselves, talk together of the risks, responsibilities and privileges of writing. On the second morning, our tutor takes out a small alarm-clock. She tells us that each person in turn is to tell their own story, what has made them who they are. But there is a time limit of one minute. As soon as the alarm goes off, we have to stop speaking, and the next person in the workshop must begin.

Each of us find ourselves in the middle of painful experience, or confusion and conflicting impulse, or even trivial detail, when mid-sentence, mid-breath, our voice is cut off. Intimate emotional and linguistic energy accumulates and has nowhere to go. A peculiar and profound atmosphere descends. The room fills with silence. It fills, too, with the desire to hear the other, to allow the other to speak. We feel an unavoidable bodily empathy for each other, an acute desire to translate this frustration and depth of feeling into poetry. What we write, though, is not our story – it cannot be – but the unspoken, the blockage, the gap.

It felt at the time strangely ironic that this workshop was held at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. I think of it now as re-embodiment. We were taken out of our rigid bodies, lifted out into the space between each other. As we wrote in the wake of interruption, we found ourselves landing inside our own flesh again, the pores of our poetic skin opened. Clear borders and separation were not so necessary.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt marginal. No matter where I am, or how welcoming people are. I suspect that a lot of poets feel similarly. The compulsion to question and explore the texture of experience, to leap and tunnel within and through language, can make you feel a little detached from any community. But some communities are more diverse and flexible than others. Some are built on what can never be clearly defined.

I first came upon the recent landmark anthology Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability through an email from Pi O. Known as an anarchist working-class poet of the local and the vernacular, Pi O has long been interested in poetic experimentations which are linked to concrete social realities, and he saw me as a poet of disability before I had claimed the mantle. I hesitated, but the anthology kept appearing in my field of vision. Eventually, I tracked down a second-hand copy online.

In it, I came upon the poetry of Laurie Clements Lambeth. Here is “Seizure, or Seduction of Persephone”:

I convulsed so hard I broke

open, broke the earth,

erupted and pushed out

a narcissus by the roots.

It doesn’t matter where

the flower broke on my body,

through the skin, a pimple,

my head, or the belly.

I could not tell you.

What I can say is this:

my limbs flailed and seized

in the bed. I watched, both

inside and outside, skin

the sheet of a Richter scale,

delicate needles charting

the shifting of earth’s plates,

limbs all speaking

unknown tongues, plotting

maps and pathways deep

into the body. As he held

me still in that bed,

how was I to discern

if he then learned

his way through the flesh

into my need, or if

he chose this blue moment

to come out, rupture

the field from within

my own unruly body?

Seduction: nothing but

a man’s hand depressing

and a flower jolting out.

Some void here between my hips.

This is not a straightforward lyric poem which is made complex by a concrete arrangement on the page, as if you could separate intent and expression, mind and body. The poem can only be experienced with the rupture of white space tearing down the page. Lambeth’s experience of seizure is given full expression, but only because we cannot fully access it. We have to read this rupture in the same way that we read the words, absorbing the noise and interruption into our own flesh.

It’s this kind of empathy and effect that I’m increasingly attracted to in poetry. It’s an intensely physical aesthetic, which draws the reader towards the embodiment of others, yet also towards their own embodiment, even towards an otherness within. It amplifies affinities, while allowing difference to be productive. Call it re-embodied poetics, or disability poetries, I’m not sure, but it encourages the sort of community that has no centre or hierarchy, where all doors and windows and questions are open, where our shared vulnerability and our diversity can be deeply affirmed.

There are so many other moments I want to mention. Finding the anthology of contemporary Australian poetry Landbridge at Collected Works Bookshop in the early 2000s. First hearing Ali Cobby Eckermann at the Queensland Poetry Festival in 2010. Kristin Prevallet’s I, Afterlife: Essays in Mourning Time. Adrienne Rich’s Twenty-One Love Poems. David Constantine’s Caspar Hauser. Kazim Ali’s The Fortieth Day. The Melbourne poetry scene, in all its openness and contradictions. Ghalib. A K Ramanujan. Judith Wright… too many ellipses…

Next week,…

1 thought on “Poetic Epigenetics: Bodily memory, silence & community”

Comments are closed.