The Strange Gaze of Justice: Words, Stones and the Moon

by Michelle Hamadache

Amine’s favourite movie of all time is The Message. It stars Anthony Quinn as Hamza and it tells the story of Islam, from cave to page. It’s got this rousing song—Tala al Badru Alayna, O the white moon rose over us—that is sung as road-weary Muslims exiled in Medina return triumphantly to Mecca. If I could hum it for you, I would, but I’d kill it for you forever (tone-deaf), so you have to imagine Amine, bent over our son’s bassinet in the dead of night, patting our little boy—a week old and swaddled up like Moses. Amine murmuring rising white moons to our son in low, modal melismas, like the lapping of the waves on the shore, slowly unwinding a moon lullaby that always, without fail, sent our little Nounou to sleep.

Amine sang it so often that even now, three children and seventeen years later, I can sing it from start to finish without understanding a single word. But I can tell you the story.

٢

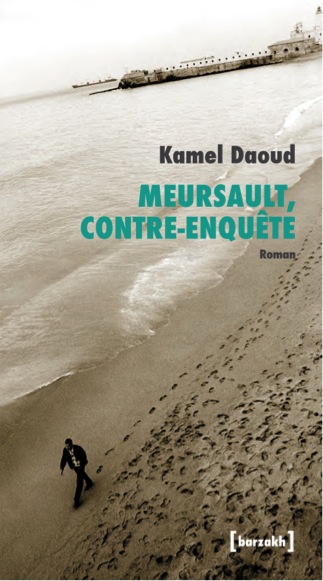

Kamel Daoud’s Algerian and he wrote a reply to Camus’ The Outsider. Daoud first published his book-reply in 2013, with Éditions Barzakh, an Algerian Press located in Hydra, a suburb of Algiers. Hydra’s high up, and set back from the sea, set back from the industry of the port of Algiers, and if you’re not tchi tchi, then you think of Hydra as tchi-tchi. A hoity-toity suburb, if you like.

Daoud’s a journalist whose work appears in Le Quotidien de Oran, La Repubblica, Le Monde and The New York Times and he first published Meursault, contre-enquête, or ‘Meursault, counter-inquiry’, with Éditions Barzakh.

In English, The Meursault Investigation.

Daoud to Camus: I’m the brother of the Arab you shot. My brother’s name was Musa. Then, into the silence left by the absence of reply from Camus, Daoud said, ‘Why didn’t you call the Arab 2pm, like Defoe called his slave Friday?’

٢

The Message is this Hollywood biblical—Qur’anic?— blockbuster made in 1976. I’ve only seen it once, when Amine was trying to recreate his childhood memory of Friday nights during Ramadan, back in Hussein Dey, Algiers, when the film would play on TV and everyone would stay home, instead of sipping black-tar coffee in the streets or visiting the neighbours. I felt for him. Our kids bought up on a diet of CGI and Pixar animations: they were a tough audience.

There are a few things that stick in my mind about our Sunday afternoon watching The Message. Apart from my children’s appalling lack of empathy for their father who clearly wanted them to fall in love with the story of The Prophet, Mohammad, peace be upon him, bringing to Saudi Arabia a religion that rejected the traditional habit of burning/burying unwanted girl babies alive, what I remember is the mascara’d gaze of Quinn at his turbaned best, and the way the camera panned out and saw the world from the prophet’s eyes.

٢

I can count to ten in Algerian. So, when Daoud makes that play on ‘2pm’, the one where he says that calling the Arab ‘2pm’ would make sense because Zujj in Algerian Arabic means ‘the pair’—we could be twins, Daoud said (3)—I feel like an insider. I already knew that zujj is number 2 and also the word for ‘pair’, but because my ear’s quite poor, I can’t hear the difference between zujj, and zwujj, which means married. Arab and Meursault, married; Daoud married. A widower?

٢

In Cologne, New Years Eve, hundreds of women were attacked, groped, robbed and raped by men. 25 Algerians; 21 Moroccans; 3 Tunisans; 3 Germans; 2 Syrians. Others from: Iraq, Libya, Iran and Montenegro. The arrested so far. (Polémique. Kamel Douad et les “clichés orientalistes”: Le Courrier International).

Daoud wrote an article in Le Monde saying that the refugees who attacked the women did so because they were living in a different symbolic order, one that configured women as objects and as a cultural site, rather than subjects. For this, a group of 11 academics put together a petition declaring Daoud an orientalist, clichéd and racist. He was accused of perpetuating the habit of European society to racialize sexual violence. Did I mention that Daoud brought in the word ‘barbarian’?

٢

Harun is the name of the narrator in The Meursault Investigation. The narrator’s brother, the Arab, the one Meursault shot, is given the name Musa.

Musa. Mu=water, sa=tree (reed).

In English, Moses.

٢

Harun: historical caliphate and a fictionalised figure from One Thousand and One Nights.

Harun, full blood brother of Moses/Musa.

Harun and his interlocutor meet in a bar, one of the last remaining bars in Oran—drinking establishments are being shut down with the re-Islamization of Algeria, following independence from France. The interlocutor is a scholar, an investigator, a literary critic, an academic? A man who came from France to follow up on the philosopher king Camus. The addressee (never named, me?) is the second person to hear Harun’s story. The first was the narrator’s lover, his first love. A woman named Meriem.

Meriem. In French, Marie. In English, Mary.

٢

At the epicentre of The Meursault Investigation, Harun fires two shots—one in the head, one in the neck— into a hapless, beach-loving, French settler, named Joseph, seeking refuge (in a well) under a lemon tree in the courtyard of Harun and his widow-mother. Joseph is hiding from the violence unfolding on the streets of Algiers in 1962, the year, the month, the day, of Algeria’s independence from France. The father (god?) deserted Harun and his mother, even before Musa was killed on the beach by Camus, so it’s Harun’s mother, the widow, whose eyes, like hands, bore into the narrator’s back as he hesitates before pulling the trigger.

Under the light of a moon, beneath a lemon tree, Harun fires two bullets, making a total of seven—how many heavens are there?—and the French settler dies. Harun’s mother is released from the immortal burden of a logic of revenge and can begin to age, and Harun himself, for the few last hours of darkness before the dawn imagines himself free from the curse of his brother’s death and free from a mother bent on mourning.

Harun imagines he might finally take in a movie. Go swimming with a woman.

٢

I keep thinking about that prophet-gaze of the camera, about the eyes, not of Quinn, but of the nameless extras who have been instructed to look into the camera’s lens as though it were the eyes of another. The slightest urge I have to recoil from gazes long gone, long dead. The ghostings of things I’ll never understand.

٢

Harun shoots the Frenchman the night independence was declared. At 2am to be precise. The date and the time are important. A day earlier and he’s a war hero, a day later a murderer.

٢

In his article, ‘Cologne, the place of phantoms’—the one that gets him in all the trouble with the academics—Daoud concludes with two questions: after we have welcomed, after we have helped, refugees and immigrants, what are the values that we share, that we impose, that we defend, and that we make understood? Beyond bureaucracy and charity, who will take on the mantle of responsibility for that? (Translation, paraphrasing, mine).

٢

Writing’s such an aggressive thing to do.

٢

In December 2014, Abdelfatah Hamadache (yes, possibly a distant relation: all Hamadaches are from Bejaia originally, a Kabyle region in the mountains east of Algiers) posted a fatwa on Facebook calling for Daoud’s death on the grounds that he is an enemy of Islam and the Arabic language and a profaner of god and his prophet. I keep thinking about the way both Camus and Daoud ended their books with hate.

٢

Harun, our narrator, in the oldest story telling convention known, is the drinking man who dreams of a man who’ll listen when he says: ‘You drink a language, you speak a language, and one day it owns you; and from then on, it falls into the habit of grasping things in your place, it takes over your mouth like a lover’s voracious kiss’ (7), which is true, a little, I guess, but only if you don’t believe in word-heaven. A place you get to not on the number of words you know, or the number of words you’ve written (phew!), but rather on whether or not you can make little souls—it doesn’t matter how many—out of the words you have.

٢

Žižek called the night in Cologne a night of carnival drives and he compares it with a ‘traditional feature of the “lower classes”’, where, in a ‘strategy of resisting those in power’ ‘terrifying displays of brutality’ are performed, aimed at disturbing the middle-class sense of decency. In the true nature of carnival, there is nothing emancipatory, redemptive or liberating about it: you know you’ll still be a refugee in the morning.

Migrants (illegal?) and refugees, neither citizens nor men, acted not because they didn’t know about the nature of freedom in the West, but because they did.

The Algerian legal system has sentenced Abdelfatah Hamadache to 6 months in prison and fined him 50 000 dinar (about $500). Daoud only wanted a token penalty. The Algerian government has been in talks with Angela Merkel about sending (against their will) home (to Algeria) illegal migrants. Abdelfatah Hamadache has appealed the ruling.

٢

I was a little bit flippant about word heaven earlier, but only because it’s what I believe in. When the page breaks, in the rivulets of white—can’t you see those half-lines in Medieval poems?—you breathe, you pause, you swim for a moment, lost. Certainty gone. Don’t you love the way beginnings and endings can bleed into one another, sift and settle, drift back on a sea of infinite whisperings?

Žižek talks about religions as clothes. Not to diminish religion’s potency, but to occupy the metaphor. The clothes are the point. The sleeve’s our heart and the academy our dress.

٢

Badiou, in ‘Our Wound is not so Recent’, was afraid that the logic of justice would unravel into a logic of revenge, when speaking about the Paris atrocities. For Badiou, if we think about atrocities as national, as identitarian, then Paris atrocities will always matter more than atrocities in Nigeria, or Mali, Algeria. The measure of the existence of the West is the difference between the response you felt when the bombs went off in Paris, compared to the bombs going off in Africa. That formula works in reverse.

There’s a strange look to justice, one that reminds me of something I can’t put my finger on.

٢

Form is political. Logic is arbitrary. I love my husband’s jokes because I never find them funny. He knows he’ll need to wait while I think things over, then I might show some belated appreciation in just how different humour is across languages, but as for just laughing out loud: doesn’t happen. Here’s a joke for you:

There’s an American President an Algerian President and a German President and they’re talking about logic.

The Algerian President says to the American, ‘So, this logic thing, explain it to me.’

‘Well,’ says the American President, ‘You’re from Algiers, it’s on the coast, right?’

‘Yeh, that’s right, it’s on the coast,’ answers the Algerian President.

‘Well, that means you’ve got a sea, see? Well, that’s logic.’

The German President whispers to the Algerian President, ‘So, can you explain it to me?’

The Algerian President straightens up and tips back in his suit, ‘Logic,’ he says, ‘Ok, you’re from Germany, right?’

‘Yeh, that’s right.’

‘You don’t have any coastline, do you?’

‘Nup, no coastline.’

‘You see—no sea, no logic.’

٢

When we visited my mother-in-law in Algeria in 2002, Amine told his mum how he was taken to the interview rooms at the airports we flew through, both in Sydney and in Rome. My mother-in-law, Fatima, said, ‘Allesh?’ (Why?).

‘You know, September 11.’

‘Eh, Allesh?’ Yes, but why? She couldn’t make the connection.

٢

There’s this moment in The Message, where Muslims are forced to flee Mecca and find themselves in the court of Ethiopia, where the King, a Christian, has their fate in his hands. He can hand them over to Abu Sufyan and his wife Hind (the leaders of Mecca), or he can offer the fleeing Muslims asylum. The Ethiopian King’s not too sure what he’s going to do: on one hand, Hind and Abu Sufyan are powerful, royalty like him. On the other hand, he’s got this fairly motley bunch of exiles before him. In the end, he decides he can’t hand these refugees over because the stories they share are too similar.

I keep thinking about Daoud and the petition of academics. I keep thinking that we’re still operating under a logic of empire.

٢

When Camus returns to Tipasa, the scene of his ecstatic youth, with the stones of empire—of Roman ruin—turned back to natural stone by the profusion of absinthe, he is a middle-aged man for whom the barbed wire of war repeats, in Algeria, as in Europe. He writes: ‘This is because blood and hatred lay bare the heart itself; the long demand for justice exhausts even the love that gave it birth. In the clamor we live in, love is impossible and justice not enough’ (168).

The thing is there’s no such thing as silence.

٢

Daoud wrote about logics and he wrote about phantasms in his article on the Cologne attacks against women. Logics/phantasms:

other/refugee-immigrant contre naïve optimism, terror.

The binary (binôme/pair/z[w]ujj) of the petrified citizen and the marauding barbarian.

Daoud identifies this discourse as belonging to the political right: it is their discourse against accepting refugees and immigrants. Daoud also says it doesn’t matter if those who attacked the women were recent or established migrants, from criminal organisations, or refugees because the phantasms don’t wait for the facts: the ghosts are already loose.

In the face of the misery of the world, and here I’m taking a little liberty with Daoud’s phantasms, when the walls of the city are penetrated: not only are the barbarians barbaric, they’re zombies: they’re already dead.

It’s easier to talk about clothes than religions.

Daoud says that refugees and migrants are constituted by the projections of the west: either victim or villain. He says that refugees and immigrants arrive in body, but not in soul, and that the culture/soul/dress they cling to because they’re alone, outside, made foreign to themselves in their new refugee clothes—are they hand-me-downs?—is often one antagonistic to western secular liberalism. Daoud talks about a group of men who see women not as citizens, as individuals, as people, but as a ‘caprice’ of the western cult of liberty because these men have grown up inside a discourse that situates women as ‘temptation’, as the incarnation of a life that must be refuted. He also talks about the sexual misery in the Arab-Muslim world.

Daoud gives his article the heading, ‘Cologne, the place of the phantasms’, because he’s not just referring to the zombie-barbarian invented by right-wing, anti-immigration discourses of the West, he’s also talking about the fantasy-phantom-object- woman-provocateur, the invention of another type of discourse. Perhaps it is because that other type of discourse is both particular to a certain Islam, but also a presence in the West, that it is so difficult to find a language that speaks for the fact that women still occupy a vulnerable position in the West today, one that can be negotiated, but not ignored.

Violence measures the potency of our fictions/phantoms.

The last word of The Outsider is execration and the last word of The Meursault Investigation is hate. Daoud and Camus don’t write for admiration. Isn’t it a type of goading to beg for howls of hate from one’s audience?

How many of us are prepared to write in the face of execration?

٢

The thing that I keep coming back to is the desire to explain and the desire to punish.

٢

Daoud wrote about attacks on women and he wrote about the aggressors, who were refugees, many of whom were Muslims. Those academics who put together the petition wrote because refugees and Islam have a bad wrap in the press, in politics. They wrote because of a political right that plays on the fears of its citizens. A right who plays the race card as though race weren’t the invention of empire.

‘The whole world eternally witnesses the same murder in the blazing sun, but no one says anything, and no one watched us recede into the distance’ (64). Logic fails in the face of the misery of the world. Logic fails in the face of rape.

٢

Daoud signed his name to an article. He wrote as both someone who knows and someone who doesn’t know. He, like the academics who signed the petition, wrote as a member of a speaking elite. He finished his article with a question, and he was answered with a petition.

٢

I wonder from where that photo on the cover of the Barkzakh edition was taken?

There’s a cathedral in Algiers, called Our Lady of Africa, built in the Roman Byzantine style in 1859, when Algeria was still a colony of France. The cathedral sits perched high up on a hill and overlooks the port and the urban, working-class squalor of the port of Algiers, of Bab el-Oued.

It’s the angle the photo’s taken on. Like someone was leaning against the curved dome of La Belle Dame d’Afrique, perhaps holding onto the cross, for safety.

What about the footprints in the sand—are they the same footprints that terrified Crusoe so very badly that he went into preparations for his war against cannibal-zombies, against the threat to his solitude? Or are they the footprints of a desert prophet who found his way to the coast?

٢

Harun, our narrator, in the oldest story telling convention known, is the drinking man who dreams of a man who’ll listen when he says: There’s always another, my friend. In love, in friendship, or even on the train, there he is, sitting across from you and deepening the perspectives of your solitude’ (73). When Harun told this story to a woman, she walked away and left him to his mother.

٢

I think about Badiou. That idea that so often when we call something evil we de-historicise it, de-politicise it; that violence, difference, knowledge belong to the realm of the ordinary, of what is already, and it’s only when art, science, politics, love are transfixed by a truth, by something new, like the way Classical music emerged from the Baroque, that we become subjects and the possibility of change appears on the horizon.

I think about Harun’s balcony in Hadjout, the one from where he looks out at his city’s ‘public space: broken playground slides, a few scrawny, tormented trees, some dirty staircases and some windblown plastic bags clinging to peoples legs’ (71-2). It’s one side of his universe. From his other balcony, the one inside his head, Harun looks ‘over the scene on the white-hot beach, the impossible trace of Musa’s body, and the sun fixed above the head of a man holding a cigarette or a revolver’ (72).

He says the scene never changes, and he beats against it like a fly against a window pane, but I think the window’s a screen and the world’s full of the clamor of broken glass and justice and the noise is exhausting the possibilities of impossible loves.

٢

When Amine sang ‘O the white moon rose over us’ to our babies he was singing them a metaphor for the way Mohammad, the prophet, peace be upon him, rose above his people and brought them the word of God. I like the moon to be the moon and it’s the only thing, apart from the sun, I like above me. What we share are metaphors, a love of melody and the light of the midnight moon.

٢

Writing, like living, is a privilege. It’s the moment that takes you to the top of the hill at Hydra, a little closer to the sky, to look at the city and the sea below. Not so you can talk down to someone, rolling words like stones to silence them. Not so that words like gravestones: here lies 2pm, Friday, refugee and woman, can turn us into ghosts, but so that we can circle, move back and forth in time, unpinned from logics. I take my pages to the hilltops to think. I want to write so that we can argue about our word-heavens, tinker—chisel and stone—away at them, and, on occasion, craft a word-soul-child together. To come down from the mountain and find something new in a basket among the reeds.

Daoud replied to the petition. He said he’d be giving up journalism. But he also said that he hates silence because its multiple definitions make such a lot of noise. When the world falls silent, it reminds him of the sound of raspy breathing (39-40), of the ghosts breathing on the other side of the wall. Except there are no ghosts: only the living rasp and dream, fail and change. Daoud wrote that he has a terror of living without sense and like all good writers he has dedicated himself to the war against cliché. He won’t be writing any more journalism. Instead he’s going to dedicate himself to writing literature.

٢ or 2

Reference List:

With immense thanks to Jean-Philippe Deranty for the links to the articles in the French Press: the course of this changed because of them.

Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, translated by Peter Hallward, Verso: London and New York, 2012

_____‘Our Wound is not so Recent’, Sequence Press, accessed: 13 March, 2016 at: http://www.sequencepress.com/pages/postings

Camus, Albert, Lyrical and Critical Essays, ed. Philip Thody, trans. Ellen Conroy Kennedy, Vintage Books (1970).

Couturier, Brice, ‘Pour Kamel Daoud’, Les Idées Claires in France Culture, 3 March 2016. Accessed: 13 March 2016 at: http://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/les-idees-claires/pour-kamel-daoud

Daoud, Kamel, The Meursault Investigation, trans. John Cullen, Oneworld Books, London, 2015

______ ‘Cologne, lieu de fantasmes’, Le Monde Afrique, 31 January 2016. Accessed 13 March 2016 at: http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2016/01/31/cologne-lieu-de-fantasmes_4856694_3232.html

______ ‘Algérie. Islamaphobie: La cinglante réponse de Kamel Daoud’, Le Courrier International, 22 February 2016. Accessed: 13 March 2016 at: http://www.courrierinternational.com/article/algerie-islamophobie-la-cinglante-reponse-de-kamel-daoud

Lahdiri, Cherif, ‘Troi mois de prison ferme pour Hamadache’, El Watan, 9 March, 2016. Accessed: 13 March 2016 at: http://www.elwatan.com/actualite/trois-mois-de-prison-ferme-pour-hamadache-09-03-2016-316125_109.php

Saliby, Hoda, ‘Kamel Daoud et le “clichés orientalists”’, Le Courrier International, 12 February 2016. Accessed: 13 March 2016 at: http://www.courrierinternational.com/article/polemique-kamel-daoud-et-les-cliches-orientalistes

Žižek, Slavoj, ‘The Cologne attacks were an obscene version of carnival’, New Statesman, 13 January 2016, accessed: 13 March, 2016 at: http://www.newstatesman.com/world/europe/2016/01/slavoj-zizek-cologne-attacks