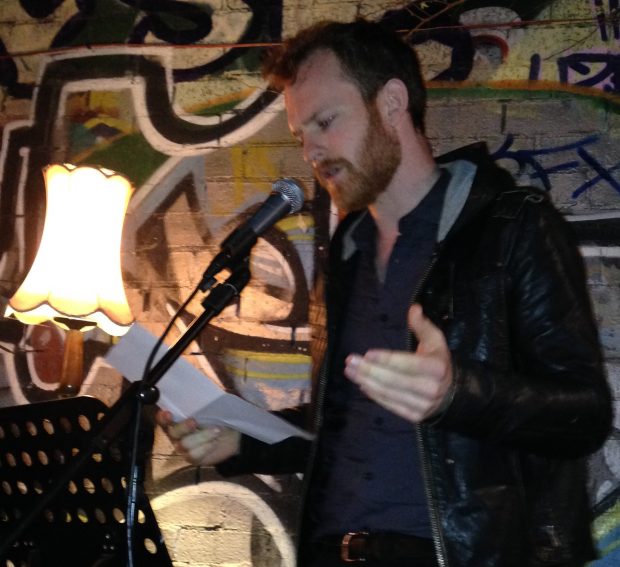

Theses on Colonial Antinomy || Jonathan Dunk

Words || Jonathan Dunk

Aboriginal writing is different. Not in any innate primitivist sense, it’s just doing different things, following different rules and patterns of relation. It doesn’t follow the straight lines that wittingly or otherwise I’ve learnt, been inculcated into – from inculcāre to tread in with the heel, knowledge as wound. When Evie and I step into the bush – the bush whose bush? a myth of uniform space – I think of bush craft, the water in my pack, the condition of the knife on my belt, memories of my melancholy bushman father. Evie thinks of spirits, she acknowledges them with more spiritual sincerity than I’ve ever felt or witnessed in cathedrals. We move on, the landscape is constantly navigated as a site of epistemic conflict and epistemic intimacy, jinga walla she calls to the black cockatoos nibbling on the banksia, the currawongs that press the windows of my crumbling apartment. The raucous cockatoos deafening Liverpool road.

She drops me off at the boom gate of a fire trail – I can’t and won’t drive, trucks and buses induce sensory overload- she leaves me with instructions, acknowledge and welcome whatever you see.

* * *

What does Aboriginal writing mean for the settler mind, what can it mean? Jameson tells us that all interpretation is uncanny, but this predicament is different. Aboriginal culture holds that land speaks, and that those who tread it are culpable to its care. David Brooks has written eloquently of this paradox, that experientially speaking there’s a grammar of scribbly gum pressed into my cheek, but it sits there as a syllable of an epic lexicography written long before I was born and a long way away from the Dharawal earth that nourished the scribbly gum. Jameson would call this syntax history, Derrida called it a bunch of things:

presence – eidos, arche, telos, energeia, ousia, aletheia, transcendentality, consciousness, God, man, and so forth[1]”,

The slippage means it’s the commas rather than the nouns that matter – a replicable relation, untethered transferability, the ethereal Cartesian self adrift in a garden of objects.

A few years ago I wrote a brutal parody/deconstruction of the journals of a number of Pacific explorers, primarily Cook and Dampier – I think it was a form of exorcism of the research I was doing:

Tho Ship be Church and Church be Ship both be wrought of Choler and Clay. The ship tho is indeed the Temple and the Body and a better aye than yr plaintive fleshly vessels God in his cups provisioned. It is the better Centaur. Do! I say, and it is done. Go! I say, and it goes. Athwart the Poop of destiny I raise my gloriously erect Prow to penetrate the foreign Surface, the Trojan trireme, the veiled Concubine, the dusky face of the Alien shore, the sea and the sea and the sea.

What tho if you find her poor? If her parting reveal only expected interiors, some Coffee or Muslin, a handful of Frankincense, or a tea-chest of fading letters? If she disappoints you, console yourself to know you never desired her singly. No brothers, Ship or Shore, she is but one further syllable of that noble Epic – Ego. Another step on the parlous tightrope strung between yourself. The Other is an Occasion.

This is the essence of the Explorer’s creed. This the Allegory – blessed be the Allegory, without it we are brutes to mouthe the Dark – of Ulysses’ death, noble Progenitor of our Guild. So, he who seeks for himself a virgin Space; must shoulder his oar & depart of himself daily to arrive every evening at another, another, he must devour the horizon of alien limit & leave in his wake number & meaning, he must plough the sea till it becomes a field, must nail his hands to the oar and pull thence until on the shore of the vast abyss beckons & he find there enthroned in the Welkin’s expanse his own image. Wherefore that winnowing-fan you inquire from the heighth, and what strange brute draws it hither?

Yeah, I was going through some stuff.

* * *

I lugged my swag and some basic cooking implements three k down hill along the bitumen firetrail that used to be Sir Thomas Mitchell’s convict cut road. Before the punt where Tom Ugly’s bridge is now it was the only route from Sydney down to Wollongong and the five islands. It’s now waterboard land, the thicket of rapids downstream of the weir is called ‘the needles’ for some reason no one remembers, and five hundred metres up the Woronora there’s a wide lake or waterhole called the lake or the waterhole. That’s where I’m headed. Woronora or Woolonora was first recorded in English in 1927 by the surveyor Robert Dixon. It’s apocryphally construed to mean either ‘black rocks’ or ‘sharkless river’. The rocks are often enough stained mauve by the tannins in the water, and I doubt bull sharks would come so far up from the Georges, but better linguistic research indicates three more likely translations:

wulan-ngurra ‘rain place’

wolaru-ngurra ‘wallaroo place’

wala-ngurra ‘then place’

Interestingly enough many Victorian name translations that were once considered evidence of miscommunication, like ‘where is it’ or the apocryphal reading of ‘kangaroo’ as ‘I don’t understand you in’ Guugu Yimithirr, are now considered accurate renditions of places named for the words spoken there by ancestors.

From a bend in the firetrail its pretty much a straight downhill scramble to a width of ambering water edged with sun blushed rocks. Its maybe an hour from sunset and what seems like literally all the sulphur-crested cockatoos in the area cometing in and out of the angophoras on the other side of the lake as I make a rudimentary camp and gather some firewood.

* * *

Modernity casts the scribbly gum as a prop, but the tree doesn’t speak the language of props, so instead it sits there shimmering at the edges of the stage shedding words. Is it the same with a poem, a novel? A text written in my language, in the same language as the Oedipal lexicography I’m dragging around. Is it though? In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) Joyce wrote that the English language always carries the syntax of its own empire:

The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine. How different are the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his lips and on mine! I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech. I have not made or accepted its words. My voice holds them at bay. My soul frets in the shadow of his language. (205)

But the Irish sea is a hell of a lot smaller than the Pacific, and the Brewarrina fish traps are far older than the fossil studded karst walls of Dún Aonghasa. Melissa Lucashenko, from her triumphant lecture at the Association for the Study of Australian Literature in 2016:

our languages never die. Because they come from country, and the country remains, they are only sleeping. In indigenous cosmology nothing is ever lost. Preempting the physicists of the twentieth century our people knew for eons that energy can never end; it only changes form. And the songlines are in the land, where they can never be lost

* * *

Modernity has an ambivalent fascination with primitive belief because it reverberates the repressed irrationalities at its core – the commodity-fetish and the evil genius of epistemology that pokes its head over the cogito’s colourbond fence, hence the constant tug of war between the seduction and the horror of primitivism. A famous passage from Heart of Darkness evokes Kurtz embrace of this predicament:

There was nothing either above or below him, and I knew it. He had kicked himself loose of the earth. Confound the man! He had kicked the very earth to pieces. He was alone, and I before him did not know whether I stood on the ground or floated in the air.

But Conrad’s primitivism is just an antithesis to rationalism, it has nothing to do with the actual beliefs or practices of Indigenous cultures, which in the Australian context have nothing to do with indulging Freudian instincts, and everything to do with respect and restraint.

* * *

Most of the evening is lovely, after the cockatoo’s sunset chorusa premature silk of purple dark gathers around my fire, which saws and eddies across the black sheen of the lake. I don’t sleep much or well. Somewhere around three or four I’m properly awake with a pain like a low band of constant pressure around my skull. I rekindle the fire and huddle around it until there’s enough dawn to make the climb. I tell myself it’s caffeine withdrawal and it probably was, but it fades when I cross the boom at the top of the fire trail.

* * *

Who is to say though, whether the settler mind’s fixation upon its own limits isn’t just another language of privilege? The physical and epistemic violence of colonialism has thrown Aboriginal writers into spatial paradox even more than settlers. Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book (2013) can be read as a recursive meditation on the trauma of Modernity, an apocalyptic closure which the author imagines extending even to ancestors through climate change:

Now the day had come when modern man had become the new face of God, and simply sacrificed the whole earth.

Jonathan Dunk is the Kenneth Reed Postgraduate Scholar at the University of Sydney, where he teaches literature and critical theory. His scholarship, fiction and poetry have been published in a wide range of national and international journals including Textual Practise, Tripwire, Meanjin, JASAL, Overland, the ABR, Cordite, Australian Poetry, and the Australian Book Review. He has been shortlisted for the Overland Victoria University prize, and awarded the A.D. Hope prize. He lives on Wangal country.