Transcendental Waters: George Miller and the cine-poetics of Miro Bilbrough

by Luke Carman

Currently, debate rages over the feminist credibility of George Miller’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi-dystopian-rock-opera, Mad Max: Fury Road. Men’s Rights Activists, apparently incensed at surrendering yet another stronghold of masculinity in their campaign to defend the manhood of western culture, have condemned the film – while progressive critics argue that Fury Road is not so much an example of radical role inversion as it is a car-chase flick that happens to put women into the action (here for more, if you’re interested). Whatever the eventual consensus on Fury Road’s gender politics, it is difficult to deny that there’s a decisively – and surprisingly – radical dimension to Miller’s film. The New York Times, for instance, offers the view that the film is a timely reminder that cinema, particularly of the blockbusting variety, still has ‘the potential to not only be art, but radically visionary’.

An aspect of Miller’s vision that has yet to be explored – at least in the critical commentary that I’ve come across – is the degree to which it manages to push a familiar set of Australian images and tropes into new territory. It is a shame, one not unpredictable, that this element of Fury Road seems to have escaped discussion of the film’s character. The classic Australian-ness of Fury Road is unquestionably part of the film’s astonishing vitality amongst the quagmire of its Hollywood remake peers. Miller’s cinematic detournement of the Australian imaginarium is not so much one that subverts an existing repertoire of tropes and types as one that takes them to a revolutionary breaking point. The fascistic tendencies of the terse, ironic, itinerant swagman become reimagined in Miller’s vision as a fugulistic convert to the cause of freedom-fighters rebelling against an all-powerful patriarch. There are myriad examples of such Australiana re-visioning in Fury Road – not all of them so de-familiarised.

The use of water as a central and symbolic motif – to select an obvious example – is one drawn directly from a patently Australian conceptualisation. In the film’s final scene (spoiler alert), the huddled masses – debased and thirsting to the point of decrepitude under the tyrannical rule of the foul overlord ‘Immortan Joe’ – are literally showered in a climactic unleashing of the junta’s water reserves. Water, source of Immortan’s power over the people, cascades down from the citadel’s reservoirs, drenching the overjoyed populous as they stand under the immensity of this release, finally freed of their enslavement and able to drink in the collapse of a brutal status quo. The waters stream out and fill the barren wasteland of this desert landscape, and an end to unbearable injustice and totalitarian horror in this small patch of a harsh post-apocalyptic world seems, temporarily at least, to be at hand.

This transcendentally symbolic use of water is one that is ubiquitous in conceptions of popular, mainstream, Australian culture – it is fundamental to everything from the suicidal swagman to the bronzed surfer riding the coastal curves – and it is one of the central themes of our literary tradition. Indeed, in the last few years alone, an astonishing array of thematic waters have played part in advancing our literary culture: Alexis Wright’s ALS Gold Medal winning novel The Swan Book is set in a swan-swarmed swamp at the centre of a semi-swallowed world – one in which the rising waters have reversed the flow of every narrative on Earth; in Kate Middleton’s poetry collection Ephemeral Waters, the poet, armed with the water-divining knowledge of an Australian, travels to a dying empire to take the pulse of its ebbing life-waters; Christos Tsiolkas’ acclaimed novel Barracuda opens with a scene in which an Australian Olympic swimmer returns to the motherland and, to the astonishment of some onlooking Brits, dives into the freezing waters before declaring himself at home in the hermetic embrace of the icy waves; Tim Winton’s Breathe also comes to mind, as does everything else he has ever written.

Whilst the reader can no doubt add a dozen other examples off the top of the head, we need not retreat into literature to find connections between Fury Road and the transcendental symbolism of water in Australian art. Indeed, on the subject of water in radical Australian cinema, it is impossible not to mention the cine-poetics of Miro Bilbrough – particularly her critically acclaimed film Floodhouse. Though not quite a blockbuster on the same scale as Fury Road, Floodhouse is, at the very least, equally as potent and surprising in its re-visioning of the Australian cinematic texture.

Whilst the reader can no doubt add a dozen other examples off the top of the head, we need not retreat into literature to find connections between Fury Road and the transcendental symbolism of water in Australian art. Indeed, on the subject of water in radical Australian cinema, it is impossible not to mention the cine-poetics of Miro Bilbrough – particularly her critically acclaimed film Floodhouse. Though not quite a blockbuster on the same scale as Fury Road, Floodhouse is, at the very least, equally as potent and surprising in its re-visioning of the Australian cinematic texture.

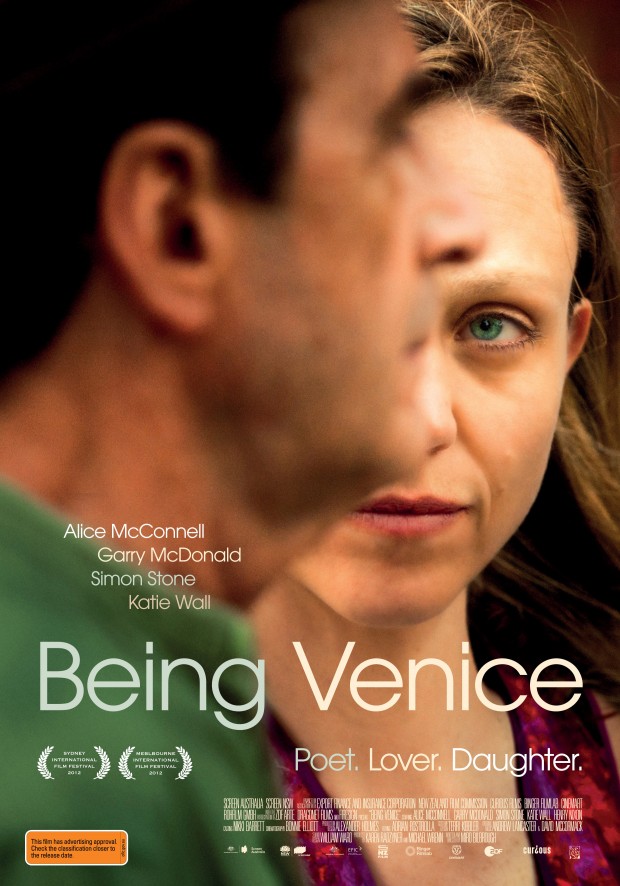

Like Miller’s Fury Road, Bilbrough’s Floodhouse is the classic achievement of popular art: an intensity of effects balanced upon a simple frame. In Floodhouse, we follow the story of Mara, a young girl who moves to her father’s ramshackle home by a remote river. There, surrounded by hippies and misfits, Mara must negotiate her burgeoning womanhood, her ruthlessly artistic and estranged mother, and the love of a local wanderer, Herringbone John. This synopsis sounds suspiciously gentle in the plot department, an accusation from which Bilbrough’s films have suffered unfairly in the past (her feature debut, Being Venice, was maligned by a handful of reviewers who no doubt will prefer the psycho-spectacular of Miller’s masculine masterpiece) but such readings are an injustice. Like Bilbrough’s other films, Floodhouse is a startling example of an alternative cinematic poetics; a poetics concerned with the lyrical, literate and intimate (the opening scene of Bilbrough’s Being Venice is one of Australian cinema’s most intimate immersions, and it is perhaps the film’s insistence on such unabashed closeness and on the un-vulgarised, non-pornographic disquiet that can be located in sensuality and the body, that left certain reviewers unable to watch). The subversive achievements of Fury Road pale in comparison to those managed by Bilbrough. For all its intensity and humanism, Miller’s film certainly cannot be credited with challenging the psychotic war-centric focus of blockbuster cinema that dominates the medium. In that respect, what Miller offers audiences is yet another murderous rampage of ecstatic sensorial violence for which our collective thirst is, apparently, insatiate.

It is not, however, the alternative poetics alone that lend Bilbrough’s Floodhouse its astonishing uniqueness. Where Miller, in Fury Road, takes the unyielding harshness of the Australian outback and sees in it an apocalyptic lens under which we might explore the indomitable longing for freedom at the heart of human experience, Bilbrough takes the phantasmagoria of the Australian bush and awakens in it an intoxicating fecundity representative of the creative capacity central to the artist, and to life and love itself. The vital saturation of Floodhouse’s setting – the hyper-abundance of life that is perfervid in every frame of the film – runs counter to the cliché of the Australian bush as a haunted, allegorical landscape of treacherous and ominous menace – a place in which the lonely, inarticulate bushman must stoically, if ironically, endure his fate. Also separating Bilbrough’s invocation of the ‘dreamy chaos’ (p.9) of this weird and other-worldly ‘bush’ landscape to conceptions that have gone before, is her explicit refusal of the typical Australian dialectics around the bush and those who inhabit it as archetypically, legitimately, Australian. The opening of the film sees Mara ferried away from a road, with the urban expanse of her childhood in the distant background. This framing is itself a step away from the mythos of Australian imagination – the world of the bush, the film makes clear, is an imaginative, unreal space divorced from the realities of the ‘real’ world by an elemental expanse of waters – the same waters that come to serve as the film’s central metaphor. The crossing of the waters in the opening scene is, obviously, a symbolic entrée into a journey of self-discovery; one in which Mara must not only become an adult woman in body and mind, but must, in the process, endure a surreal induction into the absurd psychic ‘reality’ of adulthood, with all its grotesqueries and perverse mythologies.

It is not, however, the alternative poetics alone that lend Bilbrough’s Floodhouse its astonishing uniqueness. Where Miller, in Fury Road, takes the unyielding harshness of the Australian outback and sees in it an apocalyptic lens under which we might explore the indomitable longing for freedom at the heart of human experience, Bilbrough takes the phantasmagoria of the Australian bush and awakens in it an intoxicating fecundity representative of the creative capacity central to the artist, and to life and love itself. The vital saturation of Floodhouse’s setting – the hyper-abundance of life that is perfervid in every frame of the film – runs counter to the cliché of the Australian bush as a haunted, allegorical landscape of treacherous and ominous menace – a place in which the lonely, inarticulate bushman must stoically, if ironically, endure his fate. Also separating Bilbrough’s invocation of the ‘dreamy chaos’ (p.9) of this weird and other-worldly ‘bush’ landscape to conceptions that have gone before, is her explicit refusal of the typical Australian dialectics around the bush and those who inhabit it as archetypically, legitimately, Australian. The opening of the film sees Mara ferried away from a road, with the urban expanse of her childhood in the distant background. This framing is itself a step away from the mythos of Australian imagination – the world of the bush, the film makes clear, is an imaginative, unreal space divorced from the realities of the ‘real’ world by an elemental expanse of waters – the same waters that come to serve as the film’s central metaphor. The crossing of the waters in the opening scene is, obviously, a symbolic entrée into a journey of self-discovery; one in which Mara must not only become an adult woman in body and mind, but must, in the process, endure a surreal induction into the absurd psychic ‘reality’ of adulthood, with all its grotesqueries and perverse mythologies.

The film’s first line of dialogue brings the audience into painful contact with the shame of this fantastical disharmony between the realities of the adult experience and childhood. Following the pathetic, rootless figure of her father, Harry, on a tour of the low-lying river beside his home, Mara sits for a moment on a rock – only to have her father blurt out ‘Don’t sit there – you’ll get a chill in your vagina!’ Mara leaps up, and the two, immediately ashamed and disgusted with themselves for the shamefulness of this awkward moment, endure the humiliation of the scene in silence, which manages to be both shockingly vulgar and unnervingly funny. The ambivalent ironies and sincere expressiveness of the dialogue in Bilbrough’s films is yet another dimension of their subversiveness – the lines in Floodhouse seem to settle seamlessly into the tension between the poetic and the persuasive. Though not afraid to explore shamefully tender moments between ‘grimy men on horseback’ and the ‘caustic goddesses’ who put up with them, Floodhouse, like all Bilbrough’s films, is not shy of the articulated moment. In other words, meaning is not left to landscape to pantomime for the audience – despite its symbolic role as a living entity throughout the film.

The film’s first line of dialogue brings the audience into painful contact with the shame of this fantastical disharmony between the realities of the adult experience and childhood. Following the pathetic, rootless figure of her father, Harry, on a tour of the low-lying river beside his home, Mara sits for a moment on a rock – only to have her father blurt out ‘Don’t sit there – you’ll get a chill in your vagina!’ Mara leaps up, and the two, immediately ashamed and disgusted with themselves for the shamefulness of this awkward moment, endure the humiliation of the scene in silence, which manages to be both shockingly vulgar and unnervingly funny. The ambivalent ironies and sincere expressiveness of the dialogue in Bilbrough’s films is yet another dimension of their subversiveness – the lines in Floodhouse seem to settle seamlessly into the tension between the poetic and the persuasive. Though not afraid to explore shamefully tender moments between ‘grimy men on horseback’ and the ‘caustic goddesses’ who put up with them, Floodhouse, like all Bilbrough’s films, is not shy of the articulated moment. In other words, meaning is not left to landscape to pantomime for the audience – despite its symbolic role as a living entity throughout the film.

At least in part, Bilbrough’s capacity for resisting the usual framing of the Australian bush must surely come from the fact of her cultural heritage. Though the film is shot in Australia, and cast with Australian actors, the 1970s counter-culture community that the film portrays is a semi-autobiographical importation from Bilbrough’s childhood experiences in New Zealand. In the film’s press pack, Bilbrough describes her inspiration for the film’s setting:

When I was fifteen I was sent by the Grandmother who had raised me back to my father’s house… Like Mara, I was appalled and little by little intoxicated by the wilderness I had landed in… I wanted to magnetise an audience – against their better judgement – with the unexpected beauty and tenderness of such a place. (p.9)

Like the many other artist-writers I have written about in my time at the wheel of Southerly’s blog, Miro Bilbrough brings to the Australian cultural imagination the hybridity required to avoid the trappings of an artistic climate lined with ravines of monological obsession – and this in part explains the radical nature of her courageous cinema.

In the climax of Floodhouse (spoiler alert), the river by the father’s shack floods, and the social world of this self-mythologising coterie of characters is subsumed by the elemental symbolism that their underlining denials and delusions seek to cover over. Obviously, this act of flooding is from whence comes the film’s title, but it might just be the single greatest summary of the Australian psyche ever conceived: Bilbrough’s film about the sensual awakening of a young woman manages to describe our national repressions, omissions and denials (all that necessitates our patently absurd cultural mythologies around the bush and the ‘Aussie’ who must survive it) as a doomed quixotic task. However paranoiac and delusional our attempts to hide who and what we are behind ideological imaginings, the repressed will eventually return – in this case, as a deluge which consumes the world around it. As the film’s Sound Designer, Mark Ward, puts it (once more from the press pack):

The title told me everything I needed to know… It spoke of unstoppable forces rushing through family life. Water was the central metaphor, but it was to become more than a metaphor for subconscious desires and sexual awakening, it became a bringer of change, sweeping over the character at her catharsis, washing away guilt and blame…’ (p.17)

In this consideration of Floodhouse, the film’s title becomes a dignified euphemism for an overflowing outhouse refusing to flush for the arse-end of the world. It is an optimistic, radical image – and if there is one that better distils the dreams of Australian artists in the first decades of the 21st century, I have yet to lay my tired eyes upon it.

Photo credits: IMDB