Neurological Illness in Australian Fiction

I don’t read fiction about illness much. I know that’s not what you expected, as it goes directly against the premise of this essay. But fiction allows me to inhabit another body; it’s a luxury. I’m not sure I want to read about a body that is ill like mine. Thinking about my experience of illness takes up so much of my life already: the GP appointments, the psychologist, the psychiatrist, the neurologist I haven’t yet seen but have spent nine months on a waiting list for, imagining what it’ll be like to enter that room. I’m not as well versed in sick lit as I am in actually being sick.

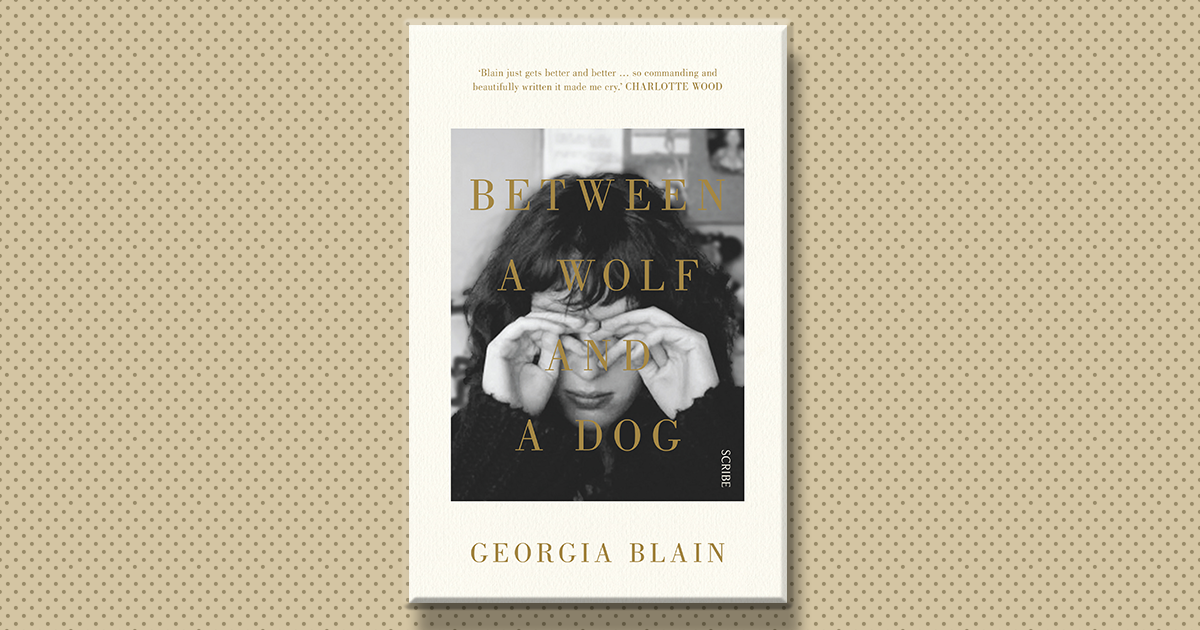

And so, I decide to come back to Between a Wolf and a Dog because when I first read it, I wasn’t sick. I didn’t know what it was like to live with neurological symptoms, but because of Georgia Blain I’d gained an insight. It was the first book of Blain’s I’d read and she had recently died. I felt the loss as I read the first few pages, pre-emptively knowing that the book was going to be special to me. Maybe it’s the present colouring the past, but I’m certain that rare contradictory feeling of wanting to devour the book all at once and slowly read it, sentence by sentence, came over me.

Between a Wolf and a Dog takes place over a day, chronicling the lives of a mother, Hilary, and her two daughters. Hilary is dying. A brain tumour. “The most aggressive kind,” Hilary tells her son-in-law. She feels grief for her own life but is not overwrought: “I’m not very old… but I’m at an age where death is less of a shock.” Blain writes of Hilary’s illness with precision. The descriptions of pain are as sparse and controlled as Hilary’s presence in the book, yet she does not dismiss Hilary’s pain: “She rubs her temples slowly, wanting to ease the pain that is beginning to creep through the pills she took this morning, its sharp nails scratching at her brain.”

I appreciate finding simple phrases I have heard myself repeating. “This is a bad morning”, or a bad day, bad week. Like Hillary, sometimes my vision “bends and warps” and I understand the physicality of her neurological symptoms. Blain writes, “She can see it in her eyes and in the tightness with which she holds herself, shoulders and back straight, face staring directly ahead.” When I’m ill, I too hold myself rigidly. Instinct mistakenly tells me to hold my body tight; if I control it, maybe I can control the blurring of vision.

Writing this of Hillary and her body, I think of another book I read during this time: Antonia Hayes’ Relativity. Ethan is a twelve-year-old boy who (spoiler) experiences seizures brought on by stress after brain tissue scarring. Ethan’s seizures manifest due to a traumatic brain injury from when he was a baby and he mistakes his hallucinations for an ability to “see physics.” Hayes writes of a seizure:

Above him, an electric arch of refracted colour scattered the wavering light of the afternoon sky. One side of his body jerked – his limbs flailed, his eyelids fluttered. As Ethan lay on his back and stared upwards, his spine bent and he began to shake. He was powerless to resist it; things fell apart. His lungs went rigid and his joints got stuck. Although Ethan saw all the colours of the rainbow, he couldn’t feel a thing.

Ethan’s worldview is shaped by physics so that when he becomes ill, he views it as his connection to science. When a neurologist tells him that his hallucinations are not science but illness, Ethan is upset: “The little boy’s eyes welled up. ‘But if I can’t see physics, then I’m not special.’” Reading this again, post-illness, it hurts more. When your vision is distorted – fixating on small details – it can be easy to fall into the duality of thinking illness represents a tragedy or gift, whether you are a child or adult. To see illness for what it is is a challenge: it is not you, but a part of you. Neither tragedy nor gift but an aspect of life whose presence grows and shrinks on any given day. It’s easy to be caught within your story of illness. Perhaps this is where fiction sits, uncomfortably wearing down ideas of my own illness. Shaping and reshaping thought until perhaps, like Blain’s Hillary and Hayes’ Ethan, I can see myself and accept being sick for what it is.

About the author

Katerina Bryant is a nonfiction writer based in South Australia. Her work has appeared in Griffith Review, The Lifted Brow, Kill Your Darlings, Southerly, Island Magazine and Voiceworks, amongst others. She has also recently been anthologised in the collection ‘Balancing Acts:Women in Sport’ (Brow Books 2018). She tweets @katerina_bry.