Eileen Chong interviews Eileen Chong

By Eileen Chong

Tell me a little about yourself.

My name is Eileen Chong and I’m a poet. I’m a bit of an accidental poet – I took Judith Beveridge’s poetry class when I was at Sydney University doing an M. Litt mostly because I was trying to avoid any modules in which I would have to write essays.

How long have you been writing poetry?

I first started to think that I might be a poet in 2009. Now I realise my relationship with poetry goes much further back than that, to when I was studying poetry in school. I think I had several poems published in a school magazine when I was 17, but I don’t consider those to be ‘real’ poems. My first ‘real’ poem was published here in Australia in 2010, in Meanjin.

Which poem was that?

It was ‘Lu Xun, your hands’, which is the first poem in a series of three. The other poems in the series are ‘Lu Xun’s Wife’ and ‘Child of the Ocean’.

Why is your name pronounced ‘E-leen’ and not ‘Ai-leen’?

Ask my mother. My theory is that it’s because my Chinese name is Yi Lin and my mother simply transposed its pronunciation into English. In saying that, though, the most common pronunciation of ‘Eileen’ in Singapore is ‘E-leen’, not ‘Ai-leen’.

Right. That must be annoying and confusing. Do you have any identity issues as a result?

I am third generation Singaporean-Chinese. Three of my grandparents were born in China – my paternal grandparents in a Hakka community in Canton, my maternal grandfather in Fujian, Anxi. My maternal grandmother was born in Singapore, descended from the Straits Chinese, or the Peranakan. I came to Australia as an adult migrant, and am now an Australian citizen. I grew up speaking Mandarin, Hokkien and English. I think, dream and write in English. I read a little Chinese, and speak conversational Mandarin. So, yes, I’m confused.

Do you consider yourself an Australian poet?

This is a question about hybridity. Am I a Singaporean poet? An Asian-Australian poet? An Australian poet? An interesting woman poet? A Chinese poet? A confessional poet? A food poet? I think I might be all of the above, sometimes all at the same time.

So what are you saying?

I think I’m saying that labels are for food, not people.

Right. You write a lot about food. Can you tell us more about this?

Like many people in Singapore, I am a little food obsessed. There is a real culture around eating in Singapore – especially around eating out. There were street hawkers from before 1960, which evolved into contained, sheltered spaces called ‘hawker centres’. This was the precursor to the air-conditioned food court of today. It’s very cheap to eat out in Singapore, although this is changing. When I was growing up in the 1980s, you could get a bowl of noodles at the hawker centre for SGD1.50. Today it’s more like SGD3 to 4, but comparative to Australia, it’s still very cheap. My maternal grandmother was a hawker – she cooked a dish called ‘fried hokkien prawn noodles’ at the Albert Complex near Chinatown. She raised six children with her earnings from this, and from other jobs.

You have written a poem called ‘Grandmother’s Dish’, which is in Burning Rice.

Yes, I have, and I didn’t intend to turn the recipe into a poem, but I did. I was missing my grandmother and this dish, which is often cooked at family gatherings. The poem is written in tercets, and its rhythm is quite staccato, which echoes the Hokkien speech patterns of my grandmother. It is a kind of running commentary-recipe that takes place across cultures. I was sitting in a café in Potts Point a few weeks ago and there were two women friends next to me having coffee. The bulk of their conversation was made up of the sharing of a recipe for pea and ham soup. One of the women, who was Asian, insisted that her pea and ham soup, without the use of spilt peas, but with fresh peas, tastes better. I enjoyed eavesdropping on the sharing of this recipe, which revealed so much about the meeting of cultures and preferences.

Cooking is also a creative act, like writing poetry.

Exactly. There is a tradition of poems about food, about the preparing of it, the sharing of it, that I am drawing on. I am thinking of Li-Young Lee’s marvellous food poems, in particular the poems on persimmons, as well as the dyad ‘Eating Alone’ and ‘Eating Together’, Sharon Olds’ ‘Crab’, Mark Strand’s ‘Coming to This’, Andy Kissane’s ‘Meat Matters’… there are so many others. Gastronomic poetry is wonderful. In fact, there was a food poetry competition called SecondBite a few years ago, run to raise awareness of a food charity in Melbourne. I had two poems shortlisted in that competition.

Which foods have you written about now?

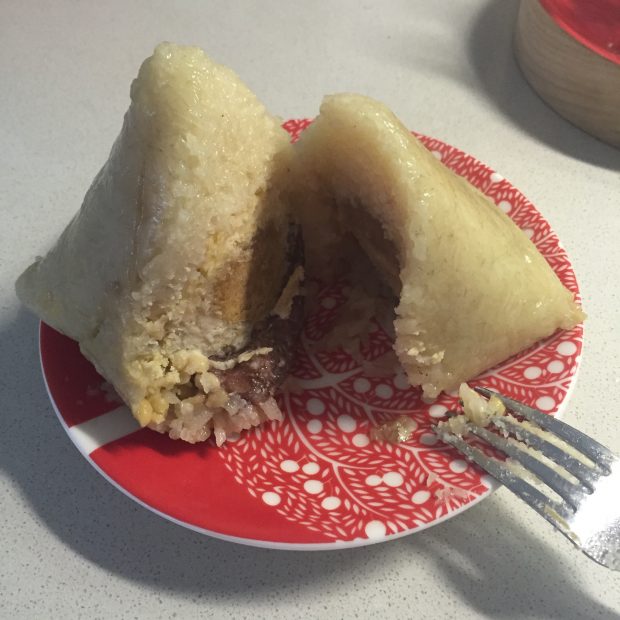

Do you want a list? Let’s see… Chinese mooncakes, xiao long bao, rice-dumplings, Hokkien prawn noodles of course… Congee is one of my comfort foods and is a bit of a personal symbol for me. And my first book is called Burning Rice! Things like mussels, bagels, lemon drizzle cake also make brief appearances in poems. In my third book I also have a poem about Scotch broth, which is a very new dish to me.

Tell us about that.

I think the poem about Scotch broth, ‘A Winter’s Night’, is a recipe poem in the vein of ‘Grandmother’s Dish’. It’s a dish from Scotland, a stew-like soup made with lamb and barley and winter root vegetables like swede and turnip. It’s the comfort food of my partner, who is Scottish. I think that one acquires recipes and foods through people and experiences in a way one might acquire history and culture. It’s about sharing, assimilation, translation, recreation, and nourishment.

Your second book was dedicated to your previous partner.

Yes, and it’s a good thing. We were together for nearly ten years. It was a relationship that had many good things about it. For one, it brought me to Sydney, where I became a poet. I’m not sure I might have become a poet had I not moved to Australia. This is also why I tend to think of myself of an Australian poet more than a Singaporean poet, although the physical and cultural landscapes of my early poems were very much grounded in Singapore.

Is your third book a collection of ‘break-up’ poems?

Sharon Olds won the Pulitzer for her collection Stag’s Leap, which she called her ‘end of of long marriage’ poems. I don’t know what my third book is. There are many poems about heartbreak in it, about grief and loneliness, but there are also joyous, hopeful poems in there. Linda Gregg and Jack Gilbert exchanged entire conversations about their relationship in their poems over the decades. I’m very porous, and I suppose to an extent, I am an autobiographical poet, because my poetry is concerned with the heart. What nourishes and underpins my work is my inability to feel any way but deeply and to respond emotionally to the world around me – whether that be towards my cultural history, my intellectual obsessions, my emotional present… I think what is important, especially in poetry that seems personal, is to remember that poetry isn’t reportage. It’s craft, it’s art. It’s truth, told slant. I guess what I’m saying is that it doesn’t really matter what’s gone on in a poet’s life – what interests me is the emotional truth in poetry, which can happen in any situation, any context.

How do you define something like ‘emotional truth’?

I’m not an academic. In fact, I’m a failed academic, having dropped out of a doctoral program, when I realised that I had nothing to say about anyone’s poetry, or anyone’s writing, except to respond emotionally to something. I was trying to write an exegesis on the poetry of Philip Levine. Whenever I read a poem of his that I connected with, I would be moved to tears… then I would write a poem in response. As you can imagine, that wasn’t very helpful for the academic aspect of the program. So I dropped out.

Do you think that was a good decision?

I wish I had found a way to complete the doctorate. Having a doctorate would be wonderful, not least because it gives you work opportunities and also the chance to be among creative academics in a supportive environment. But I was so anxious about the demands of the program and so racked with guilt about my inability to string anything intelligent-sounding together that I stopped writing altogether. That’s when I realised I had to quit; I had to protect my real work, the work of writing poetry. I really admire people who can do both. I don’t think I am one of them. This is not to say I’m anti-intellectual – I adore intellectualism. I’m just not capable of writing in that vein.

You used to be a teacher. Do you think poetry writing can be taught?

I trained as a high school teacher in Singapore, and taught for three years in Singapore. Now I teach poetry workshops when the work comes. I do enjoy teaching poetry – I like young people and I like teaching. I don’t think poetry writing workshops are about creating poets per se. I like to think of it as a match-making session – you provide the space, time and opportunity for students to connect with poems and poets, and you let nature do its work.

Before we go for this week, will you share some poems with us?

Sure – seeing as we were talking about food poems, here’s ‘Grandmother’s Dish’ from Burning Rice, ‘Rice-dumplings’ from Peony, and ‘A Winter’s Night’ from Painting Red Orchids.

Grandmother’s Dish

Buy the freshest prawns, grey ones

are the sweetest. Peel them, tails and all,

and save the shells, especially the heads.

Use your biggest pot. Heat some oil, then fry

garlic, whole cloves, and spring onion tied

into a knot. Add the shells and fry until they

turn pink. Now the pork bones. Add water.

How much? Enough. You’ll know. Bring to a boil

then let it simmer until the water turns red.

Pluck the tau gay tails, all of them. We can do it

together while we watch the Taiwanese drama.

Cook the pork belly strips in the stock

until they are firm enough to slice. Cut

the fishcake thinly, on a angle, better that way.

Now the noodles: mix yellow and white. Fry

in the wok with garlic, add prawn, pork, fishcake,

fry some more, then add a little stock. Cover

and let it cook. Be patient. Good things must wait.

Add the tau gay, then crack the eggs into the dish

and stir. Add pepper and salt now, but only white

pepper from Indonesia. Angmoh pepper not nice.

Ask who wants to eat. Don’t forget the sambal.

How to make sambal? That’s another dish. Today

is Hokkien Prawn Mee. Eat now, while it’s hot.

Rice-Dumplings

for Joyce Cutler

Bamboo leaves, scalded into olive greenness,

kept moist under a damp tea-towel. You marinated the pork

while I snipped the stems from shiitake, plump and juicy

from rehydration. Chestnuts we’d bought in a packet – here

there are no men on street corners churning them

in a wok over tarry coals. We peeled the shells

of salted duck eggs, discarding the chalky whites,

cutting bright yolks into eighths. We talked

of our mothers and their kitchens while we worked.

You chopped the shallots till you wept, wiping

your eyes on your sleeve. I laughed at your garlic

in a jar. Dried shrimp in the pan with oil, pungent

as old socks. Mung beans, washed until their green skins

slipped off. We rendered pork fat in a pan, then stir-fried

raw glutinous rice with five spice, oyster sauce, soy and sugar.

All the ingredients are ready: this is the part I came for. You hold up

three large leaves and fold them into a cone, then pack rice,

beans, meat, mushrooms, chestnuts and egg yolk into its cavity,

finishing with beans and rice. There’s magic in the way you hold

the cone, in the movements of your fingers as they pinch

the top leaf over its contents, then fold and seal

the pyramid shut. We tie raffia around each dumpling

in circles, knotting it tight, careful to leave a long string

at the end. I make small ones for your daughter. Our legs ache

from standing all afternoon; our hands are tired. We use

your largest pot and put water onto the boil, then lower

the dumplings by their tails. It’s reverse fishing. We clap

the lid on and wait. You make us cups of tea

and I cut you a slice of old-fashioned lemon drizzle cake.

What are we, if not old-fashioned? Reviving the art

of rice dumplings in an inner-city apartment in Sydney

five minutes’ walk from Chinatown. An hour and more:

bamboo scents the room. We truss up the steaming parcels

and drain them in the sink. You unwrap one in a bowl. Look

how it glistens… We eat at the counter, murmuring our approval,

marveling at our true selves, so far, yet so close to home.

A Winter’s Night

What would you like for dinner? I asked.

Scotch broth, he says. And so I peel potatoes,

parsnips and swedes; I chop onions, celery,

and leeks. I season and roast lamb shanks,

then add everything into a pot and cover it

with stock. Now to simmer for hours,

or as he said, to Cook the hell out of it. I read

that you’d give it a good stir at the end

to smash up the winter vegetables and thicken

the soup. I add three handfuls of pearl barley

an hour before the soup is ready. The meat

is falling off the bone and I cut it

into bite-sized pieces. By this time

he is on the train and will soon step out

into the cold night air towards home,

to an apartment smelling of lamb soup.

He will take his jacket off and hang it up

and bend to stroke the dozing cats

before holding me like I am something

precious and breakable. He will set the table

and pour us a drink each and sneak a taste

of the soup before exclaiming Braw!

When we sit down to eat he speaks

of his grandmother’s Scotch broth

and tells me he feels like he is in Scotland.

This, here, made from my hands,

his memories – we consume spoon after spoon

of history and desire and laugh about the future.

Photo credits: Eileen Chong