Reading Secondhand: Donald Horne in the post and Frank Moorhouse from The Record King

Ali Jane Smith

On the Monday morning after the election, with no party yet able to form a government, I turned on the radio. While I put the kettle on to make a cup of tea, ABC RN’s Fran Kelly was interviewing one of the winners, losers, or too-close-to-callers. I heard the candidate, whoever he was, say “I think Australia is a lucky country.” The water came to a boil, I changed the station.

The Lucky Country: Australia in the Sixties, was a book Donald Horne wrote while he was working for the Packers, editing magazines. The title came from a sentence in the book that read “Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck.” In his informative, evocative memoir Into the Open, Horne pointed out that, though the phrase became a household word, it was frequently misused.

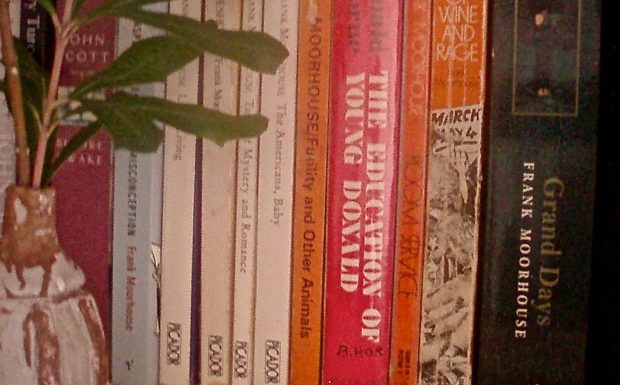

The Lucky Country sold more than a quarter of a million copies. Horne published a novel, and then the first volume of his autobiography, The Education of Young Donald. I remember seeing The Education of Young Donald sitting on the shelves of The Record King, a secondhand book and record shop. The Record King has since closed, its former proprieter now a full-time musician and music teacher. I bought a lot of Sara Paretsky‘s V.I. Warshawski detective series there, and some poetry. I also bought Frank Moorhouse’s Conferenceville, a book that might be a novel, might be a short story collection. The opening chapter is a description of an encounter on an aeroplane between the narrator and a rival who are both travelling to the same conference. The narrator wonders, anxiously, whether anyone will still be reading his books in thirty years time. The first time I read Conferenceville, I flipped back to the copyright page to check the date of first publication – 1976 – and saw that I was, indeed, reading it almost thirty years on. It has since been reissued by Vintage, and is also available as an e-book, if you want to buy it right now.

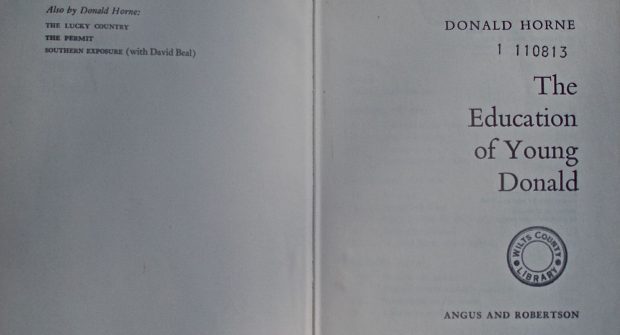

Donald Horne has a key role in Conferenceville. The narrator cites “Horne’s Rule of Diligence – miss nothing and take one of everything,” a sort of code of chivalry for conference-going that becomes a leitmotif in the book. Donald Horne’s opinion of Conferenceville, recorded in a footnote in Into the Open, was that it was “more successful, in its own way, than some of the largest works of Patrick White.” It was after a recent re-reading of Conferenceville – let’s call it a 40th anniversary reading – that I went online and ordered Horne’s autobiography The Education of Young Donald. I treated myself to a hardback, and it arrived in a tight buff envelope pasted with the address label, postage and customs declaration stickers that had granted it safe passage.

My copy of The Education of Young Donald is cancelled library stock. It was once in the collection of The Wiltshire County library. There’s still a slip of paper glued inside the front cover stamped with columns of dates due. This copy of The Education of Young Donald was borrowed several times in 1968, then in 1969, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1974 and 1975. After that there are no more stamps. Either the system changed, or the borrowing stopped.

Who were these borrowers in far away Wiltshire, Great Britain? Australian ex-pats? Republicans perhaps, or keen Austraphiles? I have a picture in my mind of a drizzly day, a housewife, in headscarf and raincoat, popping in to the library after doing her shopping, borrowing The Education of Young Donald. She starts reading it on the bus on her way home, and at first the book is a burst of sunshine. Donald Horne describes the social life of a family in the small town of Muswellbrook in the nineteen twenties and thirties. Tennis, card parties, sing-a-longs, mini golf and the pictures, holidays at the beach. But the nostalgia soon dissolves. The book focuses in on one member of that family, young Donald, his ideas, his sense of himself and his place in the world. There are events to be recorded, but as Horne wrote later, the book is about “working out how to write about oneself at some earlier period of existence.” Horne hit on what he called ‘light ironic style’. The light ironic style succeeds, but it wasn’t until I read Glyn Davis in an online essay for The Griffith Review that I understood why I enjoy Horne’s writing so much. Davis says:

Horne’s idea of a public intellectual developed as a response to experience – the thinking arose from the life. He observed his immediate world closely, and drew from this examination broader lessons about how to live and what to value.

In his memoir, Into the Open, for example, Horne writes about preparing for a family holiday:

if I put a typewriter into the boot along with the two suitcases, the carrybags, the water containers, the foam-plastic food boxes and the garbags for the laundry I can try to write ‘descriptions’, as we used to call them at school, of what we see on the way. I have put on index cards the preliminary research on Echuca, the Coorong, etc, placed rubber bands around the cards and packed them into an airline overnight bag, along with the NRMA Motorists’ Map of South-east Australia and a receipts file for our motel bookings.

The image of a car boot where a typewriter and index cards must be fitted in with food, water, and garbage bags, feels so familiar to me. The writing life mixed in with practicalities, the demands of everyday life and the social world.

The Education of Young Donald moves from boyhood to adolescence and youth, organised in the book as Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary, Tertiary being Sydney University in the Forties. Horne reads poetry (for fun!) and gets to know the young poets of his time, James McAuley and Harold Stewart. He studies with the philosopher John Anderson, a man who became an adjective, Andersonian. He spends hours in conversation with the mysterious Alf Conlon, a medical student, then the University’s Manpower Officer for the Armed Services, who can speak casually and personally of Cabinet Ministers. Horne also begins his work as a magazine editor, cutting teeth on student publications like Hermes, The Students’ Handbook and Honi Soit. He doesn’t say much about what he must have learned about the technical side of putting out a magazine, instead giving detailed descriptions of the equally vital business of in-fighting and politicking.

In the background, suburban life continues, made manifest in a Christmas tree Horne fails to decorate, a trip on the bus to see a dying Uncle, a packed lunch of sandwiches made by his mother in case he gets hungry on the train. The book closes with Horne on his way to report to the Army. The second volume of Horne’s autobiography, Confessions of a New Boy, takes up the story. One day I’ll be flush and add it to the shopping cart.

Photo credits: Ali Jane Smith