Australian Writing and Essays on Illness || Katerina Bryant

Words || Katerina Bryant

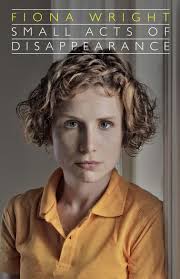

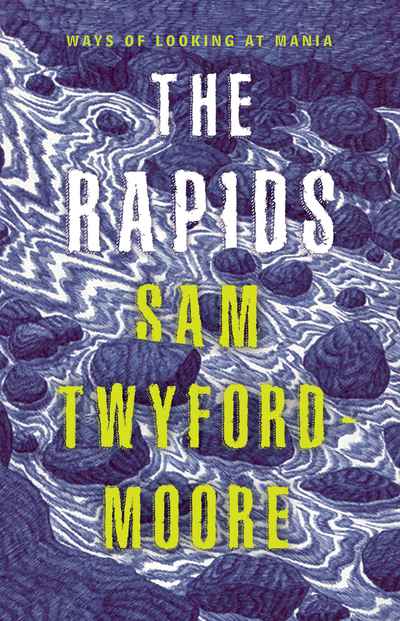

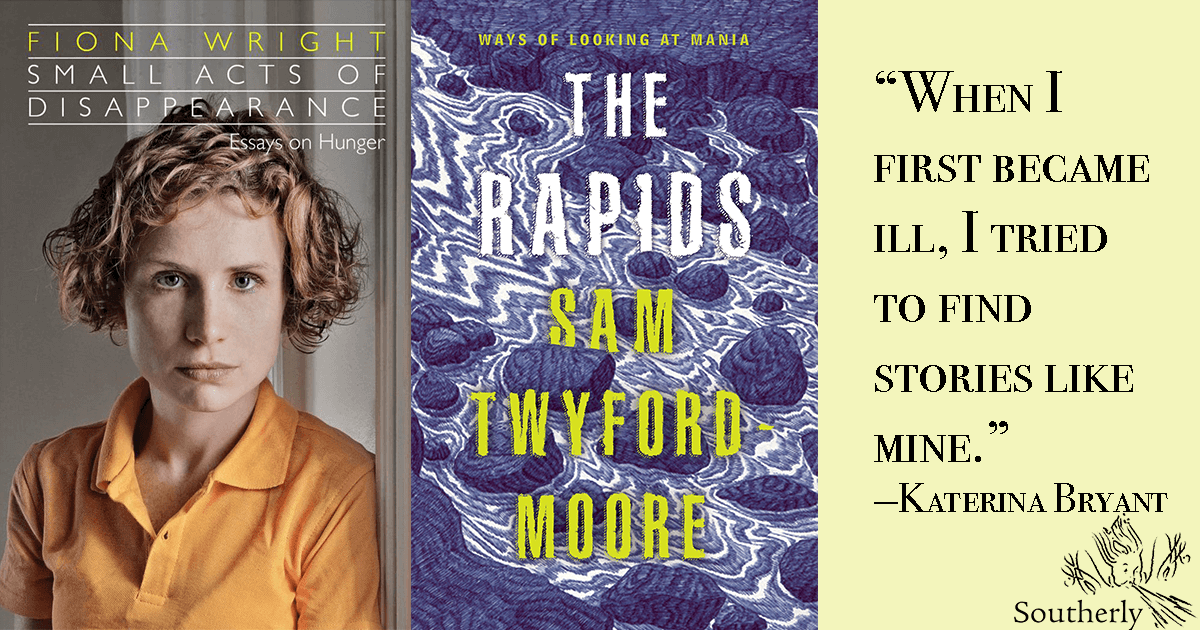

When I first became ill, I tried to find stories like mine. I needed to see myself on the page to believe I could adapt to a new life: a quieter, restrained life. I will not go into the particulars of my illness here—it is a sticky blend of mental illness and seizures that takes over the page once I begin to write about the details. But I will say that for the first few months of my illness, I left the house only for work. I did not dare live a life that could compound my symptoms. I was left with time to think, write and perhaps most importantly, read. In finding Fiona Wright’s Small Acts of Disappearance (2015) and more recently, Sam Twyford-Moore’s The Rapids (2018), I learnt that I am not alone in trying to find a blueprint for living with illness. Like me, these writers reached to their shelves to understand themselves and their illness.

It’s interesting that both writers wrote essay collections about illness. Fiction shaped their experience of illness but nonfiction became their voice. In Small Acts of Disappearance (2015), Fiona Wright talks about reading For Love Alone by Christina Stead. She describes how Teresa’s hunger and exhaustion mirrored her own experience of living with anorexia. She writes that after reading the novel at nineteen, “I recognised the physicality of Teresa’s hunger… and I carried it with me for years.” Reading your story can become an anchor. When your body becomes unrecognisable, it feels like a breath to read of another body like yours.

Sam Twyford-Moore, too, places his experience of manic depression within what he’s read. He writes of a “small, yet significant, moment” in Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift which “has grown ever more present in [his] mind and which has come, for [him], to define everything about how others look at mania”. Twyford-Moore describes the scene where an old friend watches Humboldt from afar but does not say hello because death was “all over him”. As Twyford-Moore writes, “To turn away is a great injustice” and by writing about mania, he acknowledges the lives of people with manic depression by sharing his own experience.

Wright and Twyford-Moore’s reading around illness connects past to present. Their interpretation of what they read seems to change as their bodies and minds do. As Twyford-Moore writes, “What’s weird in retrospect is how I seem to have willed some of these circumstances into being, how much I seemed to know before I knew anything at all.” He learnt about his illness in novels before his own diagnosis. In the same vein, Wright, upon rereading For Love Alone years later, notices parts of an illness she shares with Teresa that was overlooked before. She writes:

Teresa, I realised this time, has all of the character traits, from the very beginning of the book, that are said to make a person vulnerable to disordered eating… [and] almost a decade later, I recognised this sense of grasping, this need for something more, as the pulsing bass-line to so much of my life.

I wonder that if I, ten years in the future upon returning to Wright and Twyford-Moore, will know more about the nature of my illness. Will I remember what it’s like to live in my body now: reading, writing but not yet knowing?

Most nonfiction about illness lives in medical books. It is not by us but about us. The majority of my reading about illness is by the medical community. From studies in medical journals to treatment guides, I’ve read the experiences of patients whose names have been changed for privacy. I’ve read about patients as numbers, skimming over outdated dehumanising language like “emotionally disturbed” and “inadequate personalities”. In trying to find my own experience, I’ve learnt that being a ‘patient’ is not a safe space to live in. It brings the vulnerability of not only being ill, but being written about by someone who can hide behind medicalised words.

Nonfiction about chronic illness relieves me. And perhaps unlike narrative nonfiction work, essay collections like Wright and Twyford-Moore’s do not pretend there is an ending to chronic illness. These books, to me, say: Here are some pieces of a life. Let them guide you. Twyford-Moore mirrors this thought, writing, “Reading has also provided a way to form kinship. The memoirs sit beside me now in a pile, and no matter their quality, at least they say: ‘Yes, this condition exists. My experiences are broadly yours.’” Sharing memoir about living with illness is a generous act. It lets us imagine inhabiting another body; it shares the slow erosion of being ill and the triumph of living with it, in spite of it, because of it.

How can I express what it means to have Australian essay collections like these available as an emerging, ill writer? To read about these experiences feels like a reprieve. And while it means a lot that they are being written, I think it’s worth more knowing they will be read. Perhaps then, with the public briefly inhabiting the world of our bodies, chronic illness might begin to be understood.

About the author

Katerina Bryant is a nonfiction writer based in South Australia. Her work has appeared in Griffith Review, The Lifted Brow, Kill Your Darlings, Southerly, Island Magazine and Voiceworks, amongst others. She has also recently been anthologised in the collection ‘Balancing Acts:Women in Sport’ (Brow Books 2018). She tweets @katerina_bry.

Katerina Bryant is a nonfiction writer based in South Australia. Her work has appeared in Griffith Review, The Lifted Brow, Kill Your Darlings, Southerly, Island Magazine and Voiceworks, amongst others. She has also recently been anthologised in the collection ‘Balancing Acts:Women in Sport’ (Brow Books 2018). She tweets @katerina_bry.