‘Such Human-Scale Signatures’

Kate Fagan

Here is one “photograph in the brain” from Berkeley. I’m sitting with Pete at the foot of a towering sequoia. The tree is beside a small canal. Students zigzag over a bridge. Every backpack is a house. A man on a bicycle looks like Kit Robinson. The sequoia is a column of quiet, stretching from a subsonic hum in the ground. Actually the tree makes the quiet. I’m saturated in the vertigo of memories arriving before they are made. A crow on the bridge. It’s good, the imperfect drift, the narrative, the backpacks. Leaning on acres of bark I look up. Scale disappears.

Twenty years ago in northern California I walked in a coastal redwood forest. If I try to visualise those giant trees I only hear their sonic ambience – anechoic field, interior stillness, a forest floor springy and deep with needle leaves. I don’t see trees, I hear the sense of walking through them. They escape any distinct scale I have for apprehending them in memory. A whole tree is impossible to sight from the ground. Perspective capsizes, language “booms and fades”, tree noise takes over.

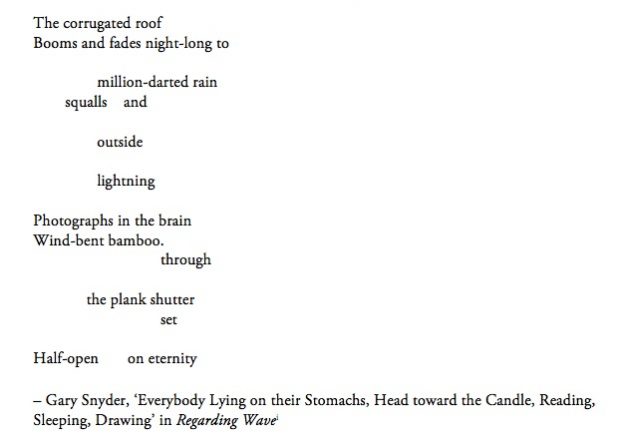

I think “such human-scale signatures”[ii] and movements of ecological regard are the absolute point of Gary Snyder’s poem ‘Everybody Lying on Their Stomachs, Head toward the Candle, Reading, Sleeping, Drawing’. Snyder conducts and re-sounds environmental scale in careful architectures. He observes a friction – figured as lightning – that occurs when boundaries of perception bump against the asymptotically infinite (or “eternal”) scale of natural worlds. Snyder’s lone full-stop is deliberate. Our attention halts for just long enough to witness one frame outside a window: “wind-bent bamboo.” Camera flash.

At this turn, Snyder doesn’t pretend an epiphany. He moves instead to reflect on how the poem’s fleeting image of “nature” embodies the limits of anthropomorphism. “The plank shutter” is “set” rather than moving like the bamboo (“wind-bent”). “Eternity” is sensed only provisionally (“half-open”). “Million-darted” and “night-long” nudge at vastness but fall respectfully short, as though nature’s sum remains “outside” human insight. Heads lean toward candles without reaching them, emblematic of Snyder’s enduring interest in Buddhist practices and teachings. From the first in this poem, Snyder makes scale his focus. The title improvises on facing other-than-human ecologies from within the constraints (“plank shutter”) of human languages, designs and actions. Despite its desire to eschew a poetics of singular revelations, it’s a hyper-romantic kind of ecological writing, open to readings that might critique its essentialism.

Flicking through Regarding Wave in Moe’s Books before Active Aesthetics began, I couldn’t help thinking of Australian poet Martin Harrison, whose striking poem White-Tailed Deer echoes Snyder’s “deer trails”[iii] while updating aspects of their eco-poetical intention. Harrison explores parallel ideas of perceptual scale in ‘White-Tailed Deer’[iv] – including the pitfalls of treating “nature” as an anthropocentric cipher for self-actualisation – while staging the poem itself as a metaphor for deep listening. Mobile and polyphonic sensory fields are invoked in Harrison’s later poems to signal the paradox of addressing ecological catastrophe and care at a quantum scale, when our imagining bodies are only human.

Two years have elapsed since Martin’s passing. It’s fair to say his voice and vision for a post-settlement, ecologically attuned poetics still resonate for many poets. I might call his influence a haunting, but that’s overstating things. Around a third of the Australian writers attending Active Aesthetics were taught by Martin or worked with him. He would have enjoyed the ironies of the sidewalk hummingbird, the aura of Robert Duncan in the Faculty Club, the uncanny eruption of a bell sounding outside Wheeler Hall at the exact moment Narungga poet Natalie Harkin spoke the line “the clanging of the mission bell”[v]. I wonder how he’d have interpreted Charles Altieri’s teleological response to Peter Minter’s account of extractive vs. proliferative poetics, or Michael Farrell’s complex suggestion that “extractive” was metaphorical while “prolific” expressed fundamental substance.

Each day of Active Aesthetics finished with poetry performances and readings. The first was a cheerful marathon in which 70 Australian and American writers traded poems over six hours, driven by the organising genius of Lyn Hejinian and Eric Falci. The reading opened with Natalie Harkin and closed with Yankunytjatjara/Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann. Somehow the hours didn’t feel long. Space expanded, time suspended, a tall regarding wave.

Martin Harrison was missed by many during those poetry readings, especially on the final night at the San Francisco Centre for New Music during a performance by Nick Keys, who has lived intermittently in the US for almost a decade. Nick’s work for Active Aesthetics was built from audio samples made while hiking in the Chiricahua Mountains in south-eastern Arizona – “a very complicated political landscape”, he observed to begin, “as all of Southern Arizona is”. The mountains are named for the Chiricahua Apache people of the Mescalero Apache Tribe who belong to the mountain region and are its traditional custodians.

Colonial stories of dispossession are not overt in Nick’s soundwork, but are included obliquely in the work’s refusal to claim certain kinds of ontological authority, which are not available to the author. A series of walks happen concurrently in the piece – some made by friends, others by hikers encountered on the way. The work shifts between audio samples and “live” spoken lines of poetry, overlaying them in places. Nick holds a conversation with his sonic fragments to riff on “life spun out from the shape of the rocks”, “a world made only of sound”, the “temporary architecture” of “recording media” and “the breath in our words [which] gives the sense of exertion and altitude”.[vi]

Like Gary Snyder and Martin Harrison, Nick Keys tests the limits of cultural and environmental scale. His work conveys only “the sense of” walking in the Chiricahua Mountains. Its cuts and lines are inexact traces of “experience”, “feeling” and perceptual constraint: “the breath, footfall, they’re such human-scale signatures”[vii]. Nick composes a poetics of walking. Or maybe he performs the sound of thinking about a poetics of walking, via digitally mediated versions of something Lyn Hejinian calls “the consciousness of the consciousness”[viii] of sonic perception. The work is not about isolated moments of thought and sound, or language as sound (and vice versa). It certainly doesn’t romanticise place, a mode that in this context would risk neo-colonial immanentism. Rather, it’s a partial account of human selves as they are remixed by complex stories and ecologies – and as they carry different access to ways of being. Everybody in this soundwork is carrying something: packs, rocks, sticks, large white squares. Subjectivity, it seems, is also a question of scale.

It’s easy to draw lines from Snyder to Harrison to Keys, when lacing together important trends in contemporary Australian and North American poetries that cluster under the umbrella of “eco-poetics”. But it’s vital to remember the recency of that imaginative and critical frame, and to honour traditions of thinking about ecology and poiesis that have existed for millennia across Australia and in the United States. These traditions were resonant on the morning Active Aesthetics began, when Vincent Medina welcomed Australian Aboriginal delegates to Ohlone Country[ix].

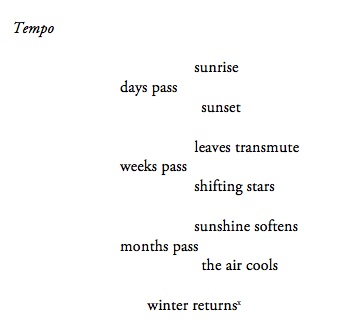

Ways of understanding links between ecology, culture and scale were addressed best in Berkeley during the keynote panel on Contemporary Aboriginal Poetics. Ali Cobby Eckermann read from her serial work Ruby Moonlight, which includes the stellar poem ‘Tempo’:

This elegant and spare lyric affirms the temporal and cultural patterns that are alive throughout Ruby Moonlight. Each line is a marker for spatialised time, an instance of ecological fact and witness in place, rather than one point along a narrative of linear duration. Every word resounds in its own locality while adding to a bigger cultural story that is both literal and allegorical. Lines work in conjunction, as might an index: they lean toward one another while bearing stories that mass like clouds behind them. In less than twenty words, “Tempo” configures vast seasonal chronicles with singular moments of weather as they are experienced by an attentive Aboriginal body – that of Ruby, who has survived a colonial massacre of her whole family.

Ruby Moonlight draws precise connections between facts of cultural memory and their slow transmission to different readers. Eckermann’s lines steadily accumulate their stories and materials, pausing between them in a manner that is both harmonic and curatorial, in the sense of care (curare) for things and their habitats. By “holding over” sound from line to line (“weeks pass / shifting stars // sunshine softens / months pass”), Eckermann makes aesthetic and cultural room for reverberations and after-images to proliferate. Repetition and suspension allow readers to reflect on the substance and story of Ruby Moonlight, while manifesting the experience of reading as simultaneously auditory, linguistic and phenomenal. ‘Tempo’ moves deftly among these different scales. Or really, it inhabits them concurrently – shifting from one person’s life in a specific place to the cosmological span of whole weathers, ecologies and cultural knowledges. To recall the words of celebrated Waanji author Alexis Wright, ‘Tempo’ suggests an ontological system for “living with the stories of all the times”[xi].

Ali Cobby Eckermann’s poems often pivot on single phrases that distil ecological and cultural immensities, including the responsibilities that come with reading ourselves as part of living environments, rather than separate from them. During her talk at Berkeley Eckermann described her mother’s Country as “a book with one chapter”[xii]. These words and their music have stayed with me. They are a portable poem holding a complete philosophy, and like ‘Tempo’, they rework the “human-scale signatures” of poetry into threaded lines of unbound story.

[i] Gary Snyder, Regarding Wave. New York: New Directions, 1970. 28.

[ii] This wonderful line comes from a soundwork by Australian poet and sound artist Nick Keys, first performed at Active Aesthetics on 16 April 2016. I transcribed the phrase when listening back to a recording of Nick’s reading (with his permission).

[iii] Gary Snyder, from ‘Long Hair’, Regarding Wave. 65.

[iv] Martin Harrison’s poem ‘White-Tailed Deer’ appears in his posthumous collection Happiness (Crawley: UWA Publishing, 2015. 51-52). I have reflected at length about the poem here.

[v] Nick Keys recalled this line while introducing his performance and Natalie Harkin confirmed the exact words to him; see note (ii) above.

[vi] Each of these quoted phrases is transcribed directly from Nick’s performance; see note (ii) above.

[vii] More of Nick Keys’ exact words – ditto for the note above.

[viii] Lyn Hejinian, “Language and Realism” in “Two Stein Talks”, The Language of Inquiry. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000. 92.

[ix] This event is recalled during my second post for this series.

[x] Ali Cobby Eckermann, Ruby Moonlight. Broome: Magabala Books, 2012. 36.

[xi] Alexis Wright, “On writing Carpentaria”, reprinted from “Harper’s Gold”, HEAT 13 n.s. (2006), 1-17. 2.

[xii] Ali Cobby Eckermann during the ‘Contemporary Aboriginal Poetics’ keynote panel at Active Aesthetics, Wheeler Hall, U.C. Berkeley on 15 April 2016.