‘Written to Music’

Kate Fagan

Leave the long fall between us (peak after peak)

Here were my paints and there were my powders

And then I was drunk and we lost each other

My shadow tumbled after

Soaking cinnamon leaves in the lake of the moon

The roll of the damned drum calls me to duty

The dice in the light of the lamp

I hear a stone gong

I lean full weight on my slender staff

Yellow leaves shaken and petals confused to my garden

The hard road is written to music

– Cedar Sigo, from ‘Panels for the Walls’ in Language Arts[i]

I’ve always loved figures of the poem as a machine for listening. A poem is a field of tempos. Poems sound out rhythms of attention and sing relations between materials that tumble and shake in time. Things endure in poetry. They remain there – given duration or lastingness – as a trace of encounters between writers and matter, mediated in “the long fall between” language and experience. This duration is deeply musical. Or rather, music has everything to do with temporality, as does poetry.

Sounds and words once seemed to me like very different creatures. As a musician I’d lose my syntactical self for a time (and then I was drunk and we lost each other). Next day I would find my paints and powders and return to the garden of language (the damned drum calls me to duty). Lately I’ve inhabited music and poetry more as parallel tools for sensing things on a continuum of tempos and scales – as allied disciplines of listening. Both are a kind of philosophical improvisation rooted deeply in ontology and sound, in being as it resonates in “full weight” over time.

‘Panels for the Walls’ by San Franciscan poet Cedar Sigo reverberates with a polyphony of cognitive associations and temporal shifts. The poem makes every sense labile and open to blurring. Each appears on a threshold before becoming another. The scent of paint rolls into loss. Tasting cinnamon, the speaker touches a lake of moon. Music from a stone gong morphs into a muscular lean, into a visible confusion of yellow, apprehended on a hard road (durus, enduring – the hard road is written to music).

Cedar Sigo was raised on the Suquamish Reservation near Seattle. When studying later at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Colorado his mentors and teachers included Anne Waldman, Alice Notley, Allen Ginsberg, Joanne Kyger and Lisa Jarnot.[ii] Sigo was one of thirty-seven American poets, mostly from San Francisco and Berkeley, who met thirty-three Australian poets earlier this year for the Active Aesthetics poetry festival and conference on which I’m reflecting in this series of posts.

I chanced into Cedar Sigo’s luminous book Language Arts the day before hearing him read in Berkeley (dice in the light of the lamp). Its imageless cover and Cagean title are a call to listen, not look. The book fell open in my hands at ‘Panels for the Walls’ and the sensation was orchestral: substance, ventriloquy, surge, body, ecology.

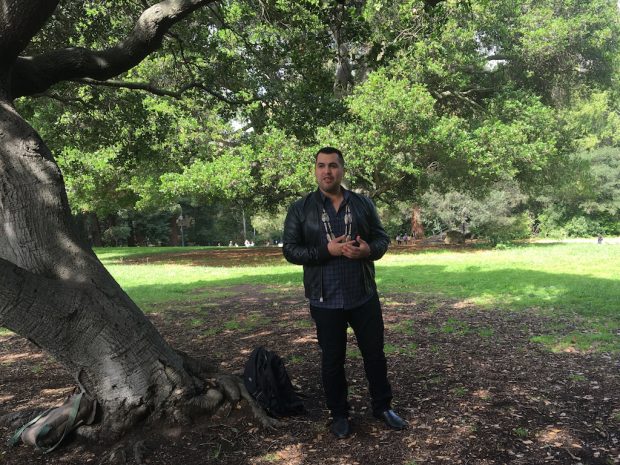

One of the deepest events of listening at Active Aesthetics came on a clear morning under a coast live oak tree in Faculty Glade at the University of California in Berkeley, which was the setting for two days of the conference. The oak fell upwards into sky. Knotted branches held compact leaves in radial bursts above a fractal, slanting trunk. Beside the glade to the north-west stood a group of soaring sequoias. Even the smallest eclipsed every roofline on campus. The wheel of earth under the coast live oak was scattered with cinnamon leaves.

Before Active Aesthetics could begin, it was vital for our participating Aboriginal poets to meet and acknowledge members of the Ohlone communities on whose land we had assembled to read. In Australia, acknowledgements and welcomes to Country honour the enduring fact of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander connection and responsibility to land. They express ongoing respect to elders and cultural knowledge in specific places, and extend that respect to visitors. After speaking with Peter Minter, who chaired our keynote panel on Contemporary Aboriginal Poetics, conference founder Lyn Hejinian invited her colleague Professor Hertha Sweet Wong to help arrange a ceremonial welcome of Aboriginal delegates by Vincent Medina – an Ohlone man of the Muwekma Tribe, who is a linguist and the assistant curator at Mission Dolores in San Francisco.

Vincent is instrumental in a community movement to recover and teach the Chochenyo language of the Muwekma Ohlone people. In 2002, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Language Committee was founded to restore the Chochenyo language that had been unspoken for over sixty-five years.[iii] Muwekma tribal members, including Monica V. Arellano, collaborated with staff from UC Berkeley Linguistics, guided by Professor Juliette Blevins, to weave together Chochenyo language from anthropological field notes and archival recordings.[iv] Some audio imprints of Chochenyo existed on phonograph wax cylinders – among the first technologies for recording and commercially reproducing sound. Many were made by the linguist John Peabody Harrington, who also notated the Chochenyo language in a detailed system of phonetic symbols.[v]

There is great pain and courage in recovering an autonomous, sovereign language via some of the machineries – state-sanctioned archives – that are enmeshed in colonial enterprises of surveillance and domination. There is also joy for cultural resistance. These ideas were addressed at Active Aesthetics by Narungga poet Natalie Harkin, who in her keynote presentation discussed her practice as an installation artist and activist-poet working extensively with material gleaned from state archives.[vi] The decolonising archival project of Vincent Medina and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Language Committee is revolutionary. Vincent’s celebrated blog Being Ohlone in the 21st Century details some of the work in linguistic and cultural reparation he is undertaking with friends and colleagues, which involves teaching Chochenyo to new generations in the San Francisco Bay Area.

When listening to Vincent speak under an oak in Berkeley, I knew none of the story of the Chochenyo language. I didn’t know the acorns of the coast live oak were a staple food for many Californian Native American peoples, including the Muwekma Ohlone.[vii] I didn’t know about the linked family of eight Ohlone languages once spoken in the San Francisco region and unheard for the greater part of a century. Colonialism is alive in silenced languages. Justice is alive in listening to ecologies of cultural fact and memory.

During his ceremonial welcome of Australian Aboriginal poets to Ohlone country, Vincent Medina spoke in Chochenyo language. His hands inscribed an aerial map, gesturing east to the Berkeley hills and west to the Bay, sketching the borders of Ohlone land. Over the past six months I’ve returned often to two things Vincent conveyed. He said, when we speak Ohlone words and names to the land, we know the land recognises them. And then he said: after so many years, we know the land is happy to hear those words again.

There is no disjunction here between sound and substance, word and thing. Matter and language are joined happily, intrinsically. The land knows its first music and is a cradle in which that music proliferates. Yankunytjatjara and Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann writes in ‘Heartbeat’ from Inside My Mother: “my heart retains the singing / the story a language // the song of owls pulsates / as trees guard the sky”.[viii] Poiesis finds expression in ecology and place, while place welcomes the re-arrival of language. In the days following Vincent Medina’s welcome to Berkeley – to Ohlone country and Chochenyo language – we circled many times around these riffs and their provocations. Like “ground-blooming flowers”, Vincent’s words set the terrain for bright conversations to come about language, poetic form, sovereignty, ruin, bodies and localities:

The poems are perfect

Laid back time machines, ground-blooming flowers

Their endless pastel grime in streaks

A blocking of my own in-expertise, a tunnel

Blown down past the marble to brass

And first to charge the shore, waving our shields

A castle left cooling to ruin

And the islands will flower in and out[ix]

[i] Cedar Sigo, Language Arts. Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2014. 13.

[ii] The Poetry Foundation includes these details on its webpage about Cedar Sigo.

[iii] See also the entry on Chochenyo language in the UC Berkeley Linguistics ‘Survey of California and Other Indian Languages’.

[iv] Vincent Medina speaks about his work here in a recent interview for Heyday Books. Additional details can be found here in the UC Berkeley media archives, including ways the restored Chochenyo language is now being taught to Muwekma Ohlone community members.

[v] For further examples of Harrington’s work see the J. P. Harrington Collection in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

[vi] Some of Natalie Harkin’s installation and archival-poetic work with the Unbound Collective can be accessed here.

[vii] The Arboretum of the University of California, Santa Cruz includes this information in a 2009 pamphlet authored by Sara Reid, Van Wishingrad and Stephen McCabe entitled ‘Plant Uses: California / Native American Uses of California Plants – Ethnobotany’ at pages 11-12.

[viii] Ali Cobby Eckermann, from ‘Heartbeat’ in Inside My Mother. Artarmon: Giramondo Publishing, 2015. 17.

[ix] Cedar Sigo, from ‘Relics’ in Language Arts. 26.