The Good Book

©Bruce Pascoe 2016

George Augustus Robinson was as randy as a turkey and twice as vain. He fornicated with the wives of his friends, the daughters of clergymen, the wives of the people he promised to save. Oh, the power of the good book and its promise of holiness. Or maybe he was just a terrific root. Or the soldiers and clergymen on whose women he preyed were too pissed to notice.

George was on a mission, a Friendly Mission. He got friendly with the wife of one of the officer’s on Flinders Island while the man was away. In his journal he disguised his triumph by referring to her as his deverry, a word apparently referring to a woman’s genitals. It’s an archaic word, since replaced by a more succinct form.

The evidence suggests that Mannalargenna’s wife, Truganinna was also his mistress and went with him when he crossed Bass Strait to try out the Friendly Mission on new victims. The Mission failed on Flinders Island as the people pined for their Tasmanian homeland and gradually died.

George was a snake oil salesman. He was some kind of builder and lay cleric in England but suddenly upped tricks and left, perhaps after a Friendly Mission on the neighbour’s wife went arse up. So to speak.

Or perhaps he couldn’t see a future for himself in the Old Dart and Australia might offer more opportunities for a carpenter who could write and sermonise.

While crossing the oceans to Australia he re-invented himself as a man of God and wisdom. Landing in Tasmania he soon tired of the chippy trade but reading about the native problem in the newspapers and hearing about it on the street corners he devised a scheme to ensure his ascent to status of gentleman.

As the penal colony at Port Arthur turned into the harbinger of massive land theft Aboriginal people fought back against the tide of Europeans. In 1824 there were only 20 attacks on Europeans but by 1830 there were 259. Two hundred and twenty three colonists died and 226 were injured. Almost every colonist lost someone in their family. Eventually, of course, Aborigines lost almost everybody.

British Military brilliance came to the fore to rid the island of the remaining menace and every available white man joined the Black Line of 1830 which swept the island from north to south in an attempt at ethnic cleansing. They caught an old man and a boy. But crikey they celebrated that resounding success just like we reckon Gallipoli is the best piece of military execution the world has seen. And Australians were there front and centre. Crikey.

So in light of this failure Robinson sees his opportunity for grandure and flash strides.

The weight of English numbers and the relentless occupation of the best land by the British hammered the Aboriginal population and the free reign of settlers to kill blacks opportunistically brought the people to their knees. The defeated army were sold Robinson’s Ponzi scheme but lighter folk, the product of thirty years of unwelcome English sperm, slipped back into the forest where some were harboured by a weird Christian cult that believed that thou shalt not kill and thou shalt not steal. Weird alright and the government made sure their Christian kindness was lampooned as treachery.

About this time Robinson offered his services to Governor George Arthur to solve the black problem once and for all. He proposed to employ his blarney to encourage the remaining First Tasmanians to leave Tasmania for a short period while the Government sorted things out so they could return to a more peaceful clime. This promise is like a cashback on the purchase of a frij. It’s free money, right? They’re paying you to take the frij off their hands. Capitalism and Colonialism are devil children and we sing all sorts of songs and mouth all kinds of oaths in their honour.

But Truganinna and Mannalargenna were not fooled. They recognised a Ponzi scheme straight away but they had only two alternatives. Nothing and less. The war was over and their lot was to be the people to hand over the keys.

But Robinson was upbeat as all hell and promised them all sorts of trinkets and beneficence from his God, the God of failed carpenters. He could afford to be upbeat. The sleight of hand had delivered him a fortune of which he could never previously have dreamed. He had a house, he was invited to dinner at the homes of lords, his clothes were the height of fashion, if a little foppish, and he wore a gentleman’s trousers. Most of the time.

So Robinson’s Friendly Mission is an outstanding success. His fashion consciousness has convinced him to wear a tall soft hat that flops on his head like a dead chook, but he reckons it’s a sure winner with the deverry and wears it on the ship as he leads his flock to their heaven, their haven.

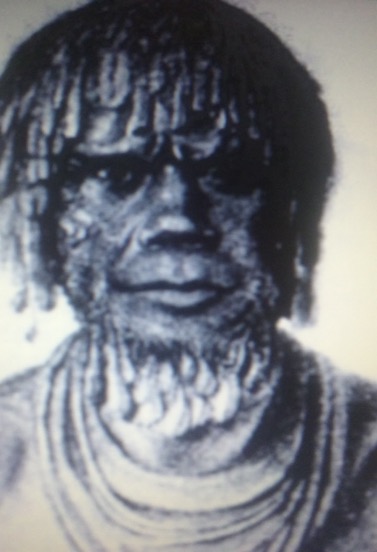

Mannalargenna is also in possession of impressive head gear. This great warrior of the Resistance treats his dreadies with grease and ochre and is a formidable sight. His pride is apparent to any who see him, he is a very impressive man.

Robinson, heraldic in the bow, dreams of the opulence sure to reward his outstanding success as the brave craft approaches Big Green Island. Behind him Mannalargenna takes a knife and slices through his fearsome locks and piece by piece he casts them away.

At least one person on board knows what is really going on and that person knows that when a warrior is delivered to a prison he has no need of pride. And without that pride dies a couple of months later.

Robinson tries his Christian colonial trade in Victoria and spends a lot of time at the tailor. He takes Truganinna with him but then tires of the native. She’s too political. He abandons her and later returns to London wearing pants that cost a year’s salary.

Almost every Tasmanian Aboriginal is related to Mannalargenna. We grow our hair in his honour. An antidote to despair.