Agreeable book reviewing is a dangerous, vapid “epidemic of niceness”

Words || Jack Cameron Stanton

Over the weekend I visited my parent’s house for brunch with the Lebanese side of the family, and in order to cater for political differences I strolled to the service station and purchased The Weekend Australian and Sydney Morning Herald. Over a breakfast of fresh manoush and lahembajin, the Lebs scoffed at two wildly different headlines—‘SCOMO LEADS A NEW GENERATION’ vs ‘MORRISON SNATCHES TOP JOB’ (I’m sure you can guess which is which)—while I slid out the review sections of each paper to examine them. The Weekend Australian offered six pages of substantial book reviews, and although most of them were advertorial in tone, bombarding the reader with praise of each book’s literary merits, there was a feature excerpted from Germaine Greer’s cauldron-stirring book On Rape.

The Spectrum, however, had a double-page spread devoted to the Miles Franklin shortlist authors giving their own books a plug, followed by a half page of one paragraph reviews on eight books—four fiction, the other non-fiction. And that was it.

The reviews were more synopsis than analysis and the superlatives that always make me paranoid of advertisement. The result? A vapid, unproductive “epidemic of niceness.”

With book reviewing integrity increasingly difficult to find, there’s a renewal of significance placed on literary journals and other digital spaces that uphold the critical dialogue among readers, critics, editors and writers alike. In many cases, the public sphere’s desire for discussions of literature has been frustrated into paralysis, with Sydney Morning Herald’s The Spectrum—once a weekly tome of literary news—becoming a spectre of its former self.

There’s hope, however. Since 2013, the Sydney Review of Books (SRB) has published long-form essays about Australian and international writing. Although primarily an online publication, in December 2017 SRB published a print collection of essays called The Australian Face, which, according to editors Catriona Menzies-Pike and James Ley,

mak[es] a claim for the enduring value and vibrancy of a certain kind of long-form critical writing. The five-year period of the Sydney Review of Books has not been a particularly easy time for Australian writers. It is not just that key funding sources have been cut, which has diminished available fellowships and funding to literary journals, but also that there has been a demoralising public debate about the value of the arts, in which politicians have been reluctant to voice their support for artists, writers and publishers.

Demoralising indeed!

The opening essay by Ben Etherington, “The Brain Feign”, cautions against this “epidemic of niceness” in reviewing culture by making a case for harsher, more frank and less agreeable criticism. “Thin criticism turns reviewing into infomercial, allows established writers merely to churn out material, reinforces industry nepotism, and denies new authors the reception they need to flourish,” Etherington writes. In other words, idle and unjustly praised review work aggravates the possibility of anhedonia in our writing culture. It enables revered writers to slump into rote learnt, mechanical, formulaic novels: from Irvine Welsh to James Patterson, the pressure of consumerism on novelists to produce work according to certain publishing guidelines has certainly proven itself non-conducive to intellectual vibrancy and artistic innovation.

He goes on by criticising the 2012 Miles Franklin award-winning novel All That I Am by Anna Funder, a book he ultimately considered an “airport Nazi espionage thriller dressed up as literature,” citing throughout his essay a bricolage of narrative incoherence. Funder, he concludes, may very well be a mediocre fiction writer.

But after reading every review he could find, Etherington discovered his view was an unpopular one, and many reviewers showered Funder with superlative-heavy praise used to the verge of exhausted meaninglessness. “All That I Am is a novel that questions the ubiquity of human conscience,” one reviewer writes; “a passionate and intimate story [that] sucks in a reader as the characters are sucked down into the Nazi vortex” says another; and the irrelevancy of this baseless personal waffle, “Hans is, for me, one of the most interesting characters in the novel.”

It would be easy to pull the literary-snob card if this nihilism didn’t signify literature’s obliteration.

What do any of the above quotes actually say? They give the impression of being substantial while simultaneously saying nothing, offering no allegiance. “None of the critics work to demonstrate why exactly the novel deserves it,” Etherington writes. Not all that glitters is gold.

Most good fiction promises to tell the reader one story while actually exhuming a different one altogether. Pretty much every essay published by SRB strives to unearth the other story and two pieces do this exceptionally well: Julieanne Lamond’s case for Christos Tsiolkas’ Barracuda (2013) in her essay “The Australian Face”; and “Gut Instinct” by James Ley, a reflection on Helen Garner’s empathetic approach to true crime writing in This House of Grief (2014).

Christos Tsiolkas

At first glance, by writing Barracuda Tsiolkas exposed himself to being criticised as a bigshot writer selling-out by writing a novel that delves into Australia’s perceptions of sport—specifically Olympic swimming, and even more specifically the violent insanity that national pressure and pride cause within his protagonist Daniel Kelly, an aquatic savant destined for Olympian glory from a very young age.

The novel is a syncretism of his earlier work’s Dirty Realism, as seen in Loaded and Dead Europe, and a microcosmic bildunsroman that, in Lamond’s words, contemplates “the affective pull and the sharp edges of community: ethnicity, family, friendship, class, nation. He dismantles the national idea of ordinariness without discounting the force of nation and belonging.” Lamond claims that Tsiolkas uses his queer Greek lens to “view the mainstream from the outside.” And, arguably, a genre is hardening, with Sweatshop writers Peter Polites, Michael Mohammed Ahmad and Luke Carman; Indigenous writers such as Alexis Wright and Ellen van Neervan; even Michelle de Kretser and Maxine Beneba Clarke.

The deft reader will cast aside any presumption that Tsiolkas’ artistic decisions were motivated by mainstream interests after acknowledging the novel’s macrostructure, in which we are given the narrative of Danny’s life in alternating chapters to each end of the story’s timeline. They work backwards and forwards respectively: an eager, young Danny hungry for glory is juxtaposed with a jaded and depressed Danny who is trying to rediscover his dignity after a stint in prison. In that sense, Barracuda is much less about the swimmer Danny than it is about The Australian Face, as Lamond observes in an early passage set in Glasgow:

I look at the man selling me the ticket and I see a stern, long-chinned Australian face. I run to catch the train, slip through the turnstile past the elderly man checking the tickets; he too has a ruddy Australian face . . . Clyde said to me the other day, ‘Pal, do you think you might be seeing the Australian face everywhere because you want to?

Australianness thus rendered hallucinatory, a mere matter of perspective, Tsiolkas captures a convincing portrayal of national identity as inherently violent, coercive, alienating and unforgiving of failure. Meanwhile, Lamond’s review accomplishes what all great reviewers strive for: by offering a different and informed perspective, it changed my mind about the book.

It seems unlikely that Helen Garner will ever live-down the controversies of The First Stone (1995) which caused fury among Aussie feminists who perceived it to be dangerous and unethical that Garner adopted a sympathetic approach toward an alleged sexual harasser at Melbourne University’s Ormond College. But in his essay “Gut Instinct,” James Ley writes that the very empathy that makes Garner compelling is “also what gets her into trouble.”

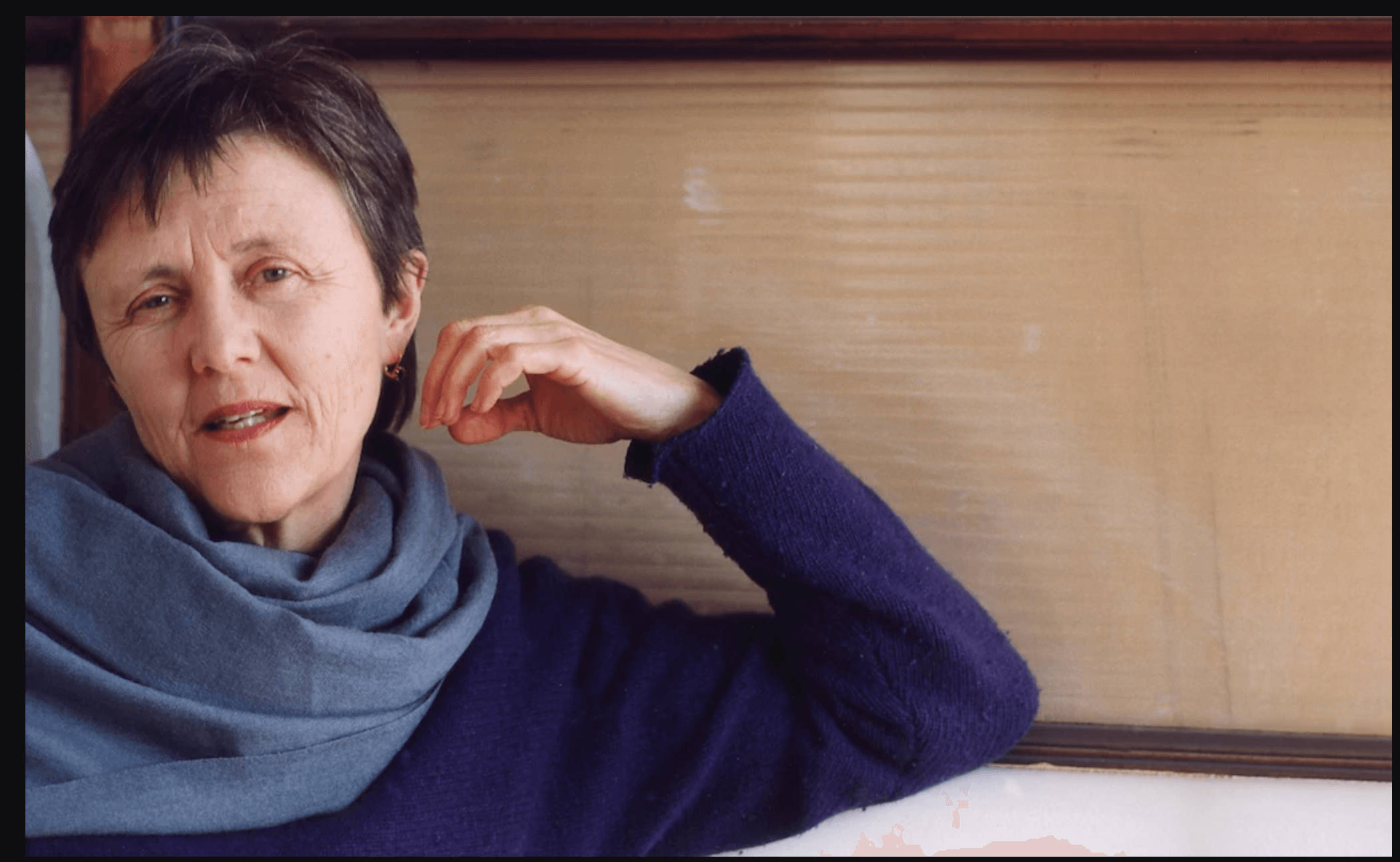

Helen Garner

I recall seeing Garner at City Recital Hall in May this year as part of the Sydney Writers’ Festival, a rare public appearance that sold out weeks earlier. Garner described her narrative persona as a beam of focus bouncing from object to object, guiding the reader along. Could Garner’s solipsistic-style of writing court procedural narratives be a more frank and honest approach, a kind of naked subjectivity, than trying to infer a degree of objectivity? While “slow-grinding” court procedurals form the “narrative spine” of Joe Cinque’s Consolation (2002) and This House of Grief, Garner humanises these potentially dry and technical behemoths by “striving to cultivate a sympathetic and indeed empathetic understanding” with victims and criminals alike. For some readers, this sympathy may be at times unpalatable in This House of Grief when Garner considers the mental and emotional state of Robert Farquharson, who drowned his three children on Father’s Day 2005 by driving his car into a Victorian dam. But part of Garner’s representation of him emphasises his ordinariness, even oafishness, once again illuminating the dark terror of evil’s banality.

Reviewing is not only significant for its quality control function, as defended by Ben Etherington, but also because deep inquisition into the mechanisms and psychologies of narrative greatly enhance the levels of meaning we can extract from them. Sydney Review of Books remains one of the final guardians of viewing the mainstream from the outside. Stinson’s essay channels the words of Phillip Edmonds by calling these dialogues “quiet conversations in a very noisy room.” Quiet though they sometimes may be, these conversations are vital to the ongoing enrichment of Australian literary culture, because as Stinson surmises:

whether or not little magazines are idealistic enterprises, they are essential to contemporary literary culture: they showcase new and emerging writers; provide a training ground for editors and administrators; offer more extended literary debates and discussion than the broadsheets; comprise a venue for journalism that contains views outside of the liberal mainstream; serve as rallying points for different communities of readers and coteries of authors; and present a steady stream of readings. events, panel discussions, and online conversations through social media.

The Australian Face: essays from the Sydney Review of Books; edited by James Ley and Catriona Menzies-Pike; Sydney Review of Books; ISBN: 978064806103; $29.99

Jack Cameron Stanton is a writer and critic based in Sydney. His work has appeared in The Australian, Southerly Journal, Seizure, Voiceworks, and Neighbourhood Paper.