Farewell, Bourdain: why I stopped being a vegetarian

Words || Jack Cameron Stanton

Before I tell you about how Anthony Bourdain made me question my long-standing vegetarianism, I need to get something off my chest. When I heard Anthony Bourdain died I became fearful, because I no longer believed anybody was safe, that if he could feel miserable enough to hang himself on 8 June 2018 in his Le Chambard hotel in France while filming Parts Unknown—then it could happen to anyone. Once the emotion of losing a lifelong role model waned I read into the murky realities of what had happened. Bourdain died by hanging himself with a bathrobe tie in a Kayserberg, France hotel room while filming Parts Unknown. At the time, Bourdain was dating an Italian actress Asia Argento, a pioneer in the #MeToo movement who made allegations of sexual assault against Harvey Weinstein in 2017. The couple met in 2015 during an episode of Parts Unknown in Rome, and since then they had made headlines for activism against Weinstein and more broadly the abhorrent sexual exploits of unchecked Hollywood monsters.

But just this month, in the New York Times, it was reported that “in the months that followed her revelations about Mr. Weinstein last October, Ms. Argento quietly arranged to pay $380,000 to her own accuser: Jimmy Bennett, a young actor and rock musician who said she had sexually assaulted him in a California hotel room years earlier, when he was only two months past his 17th birthday.” To make things worse, Argento was stalked by Italian paparazzi who published photos of her cheating on Bourdain with French journalist Hugo Clément on 7 June, one day before he committed suicide.

In Bourdain’s swansong, an article published in The Hollywood Reporter on 2 June 2018 called “My Cinematic Dream: Filming With Asia Argento and Christopher Doyle in Hong Kong”, his closing sentence is “As you might have guessed, I already have an Asia Argento tattoo,” perhaps alluding to how smitten Bourdain was with his newfound love.

Arguably the only thing he loved more than Argento at the time of his suicide was food, and since the man was driven by passions—maybe even driven to suicide because of it—I started to examine my own ethical stance against eating animals.

But the problem is this: everything I knew about Bourdain has been touched by an interloper: television, the internet, his writing. And apart from (or even contributing toward) the shock, the tragedy of it all, Bourdain didn’t publicly betray any signs of depression in any of his public persona—apart from his fondness of drinking. All of it processed through simulations, presentations, symbols, images.

So how could a simulation, a romantic, distilled avatar of the real man convince me, a long-term vegetarian, to try eating seafood?

It seems like a foolish and selfish question to present forward as the premise of a discussion about Bourdain’s death because it deals so much with how Bourdain has affected me and my thoughts, but this lens also offers peculiar insights into how we interact emotionally with the avatars of our admiration.

I have been vegetarian for over ten years, but on 9 June I started nibbling at seafood, and since then I have worked on my food resume. What have I eaten? The first time I tried fish was with Stephanie for lunch at a sushi train on King Street, where I picked at her salmon sashimi and ate a tuna sushi roll, which admittedly I didn’t like, too much mayonnaise and a kind of fishy kick-back.

But after that?

Pippies cooked in XO sauce with fried vermicelli served with a plate of steamed Barramundi in ginger and shallot sauce from the insomniac’s favourite Golden Century in Sydney’s Chinatown. And sea scallops, steamed, with a light garlic soy sauce, served alongside Kingfish sashimi drenched in chilli oil from Queen Chow on Enmore Road. The day of my job interview at Woollahra Library I snuck to the sushi train in the food plaza beneath it, and after some agedashi tofu and green tea I grabbed a plate of salmon nigiri off the train and dabbed it with wasabi soy. Or how about the other night on my mother’s birthday, Friday 10 August, when we had dinner at Bistro Felix in the CBD, where I tried my father’s entree of seared tuna coated with a buttery mustard sauce and instantly wanted to send back my plate of gnocchi with pumpkin and sage and plenty of butter for what he’s having. After that financially reckless toss into the world of seafood, I found myself increasingly curious in the various textures and flavours awaiting me. Soft-shell crab, bugs, prawns, fried fish, and of course, oysters. About four disinterested bartenders and friends of mine have repeated the identical phrase “welcome to the world of fish”.

Bourdain’s passion for food is the obvious-and-therefore-unconvincing reason that I considered eating seafood. But it still matters, because he recognised food as a gateway to understanding cultures. Anyone who has watched No Reservations or Parts Unknown or The Layover will know that Bourdain is the proverbial fly on each culture’s wall, even his own. He will eat anything: I recall when he visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo and sat among a tribe who ceremonially butchered a cow and then hacked it into various sizes of flesh which were cooked above a fire beside the Congo and then fed to a laissez-faire, unbuttoned shirt Bourdain.

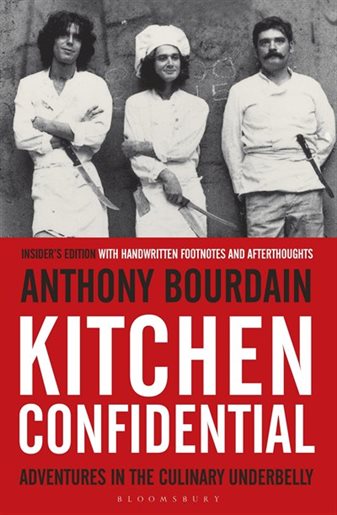

In Kitchen Confidential, Bourdain recalls a time in his life as a young boy in a tiny French oyster village, La Teste du Buch, where his family was invited by their next door neighbour, an oyster farmer, out on his pinasse (oyster boat). After a lunch of brie and baguettes, young Bourdain complains of still being hungry. Hearing his complaint, the fisherman leant over the side, “reached down until his head nearly disappeared underwater and emerged holding a single still-encrusted oyster, huge and irregularly shaped.” He ate the oyster, tasting the sea but also envisioning a future (or so he recalls, romantically) because not only did he survive his first oyster—he enjoyed it.

What I’ve neglected until now, precisely because the discourse requires itself distinct attention, as has been done by Jonathan Safran Foer in Eating Animals, is the ethical thorns of denouncing a degree of vegetarianism in favour of eating animals again—in my case, seafood. I have had much time to contemplate what has happened in this ideological maelstrom. As I mentioned earlier, Bourdain believed food was the great equaliser, the reassurance of our mutual humanity, the gateway to culture. Part of the dissonance here is an incompatibility of ideologies. At the end of Kitchen Confidential, Bourdain travels to Tokyo where he is enraptured by their deep reverence for food. He ducks into five-seater sushi joints and eats myriad raw sashimi. But here’s the thing: it’s not as though Japan is about to stop eating seafood.

Eating animals is wrong, just like lying and stealing—and yet we all indulge in the latter, admittedly some more than others. So—and I’m lifting this argument from Jonathan Safran Foer— why is vegetarianism populated by this ‘you’re in or you’re out’ mentality that uses hypocrisy to criticise anyone who doesn’t deal with moral absolutes? Imagine always or never lying, Safran Foer suggests.

The idea of moral absolutes is itself paradoxically hypocritical. The issue is that strict vegetarianism doesn’t tolerate a spectrum. Even hardcore vegans are often scornful of their vegetarian counterparts. I recall one afternoon in Melbourne many years ago. I approached a vegan activist on Collins Street and said I was vegetarian transitioning to vegan, and that I couldn’t imagine ever eating seafood.

“Sea animals, they’re sea animals, man,” is what he said to me, before hoisting his placard that read MEAT IS MURDER.

But the point I’m trying to make is that the ethics of eating animals deal with absolutes: killing animals is wrong. Lying and stealing are multivalent and circumstantial; we forgive occasional transgressions, if they are justified according to whatever moral skeleton holds us upright. But to counteract this argument, as a society with the choice not to eat animals aren’t we then morally culpable for doing so? What justification then? I find myself resorting to Bourdain’s belief of food as the gateway to culture. Like I said before, the Japanese aren’t giving up sushi anytime soon.

In the preface for Kitchen Confidential, Bourdain writes: ’The only people who seem to really hate me for this book are the folks who write articles on mayonnaise and “fun with French fries for a living—and, of course, vegetarians, but they don’t get enough animal protein to get really angry.” And in case he hadn’t made his views clear, Bourdain reiterates again later in the book: “Vegetarians are the enemy of everything good and decent in the human spirit, and an affront to all I stand for, the pure enjoyment of food.”

Jack Cameron Stanton is a writer and critic living in Sydney. His work has appeared in The Australian, Southerly Journal, Seizure, Voiceworks, and Neighbourhood Paper.

Jack Cameron Stanton is a writer and critic living in Sydney. His work has appeared in The Australian, Southerly Journal, Seizure, Voiceworks, and Neighbourhood Paper.